Five stars. The title translates to “Delicious in Dungeon.”

Two long-running manga series that I had been following for a long time ended this month: the first one, Oshimi’s Chi no Wadachi, and the second one is Kui’s wonderful Dungeon Meshi. More often than not, when I finish a manga series and I’m starving for more of the peculiar joys that this format provides (far higher joys than what most of Western fiction produces these days), I check out lists of recommendations, plenty of which mentioned Dungeon Meshi. However, I always passed on it. You see, a fiction genre somewhat popular in Japan focuses on weird food-related tournaments that mostly seem like excuses to draw mouth-watering food, and print recipes. I never saw the appeal, and I wasn’t interested in a variation of that formula even with a fantasy dressing.

Big mistake. Dungeon Meshi is an exceptional story with fantastic characters, and the food-making part works as a straight-faced satire, because the vast majority of the recipes involve cooking D&D-like monsters into something resembling edible food. The whole deal about making elaborate food out of monsters could have been a gimmick, but the plot turns it into a necessary element to survive.

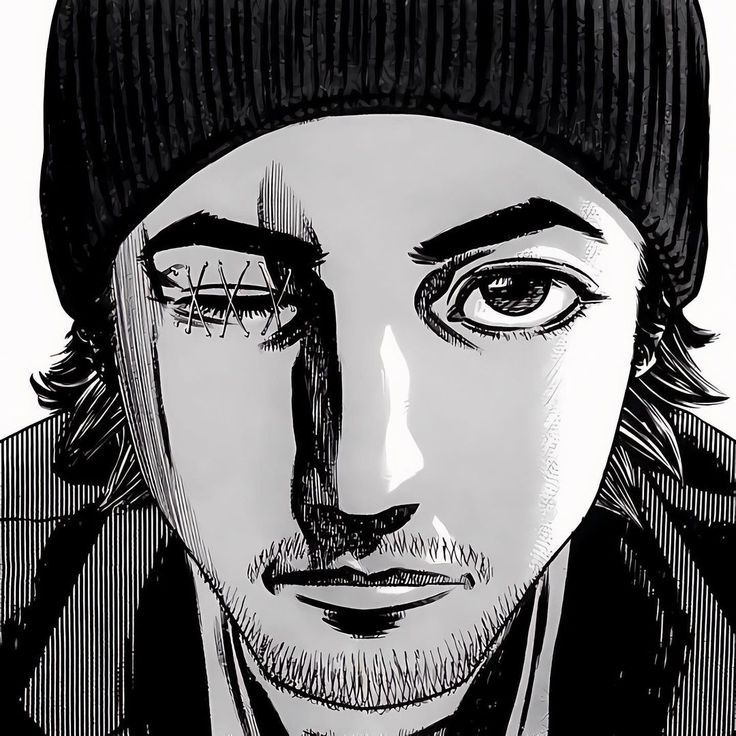

The tale introduces a group of adventures who don’t get along with each other very well. The leader, the fighter of the group, is an obsessive, socially oblivious maniac (could easily pass for autistic) who dreams of tasting every monster in the world, and who possibly also wants to become a monster. He’s accompanied by his sister, a laid-back, eccentric sorcerer. Apart from the siblings we have an uptight elven wizard, a pragmatic halfling rogue, and a barbarian dwarf merc.

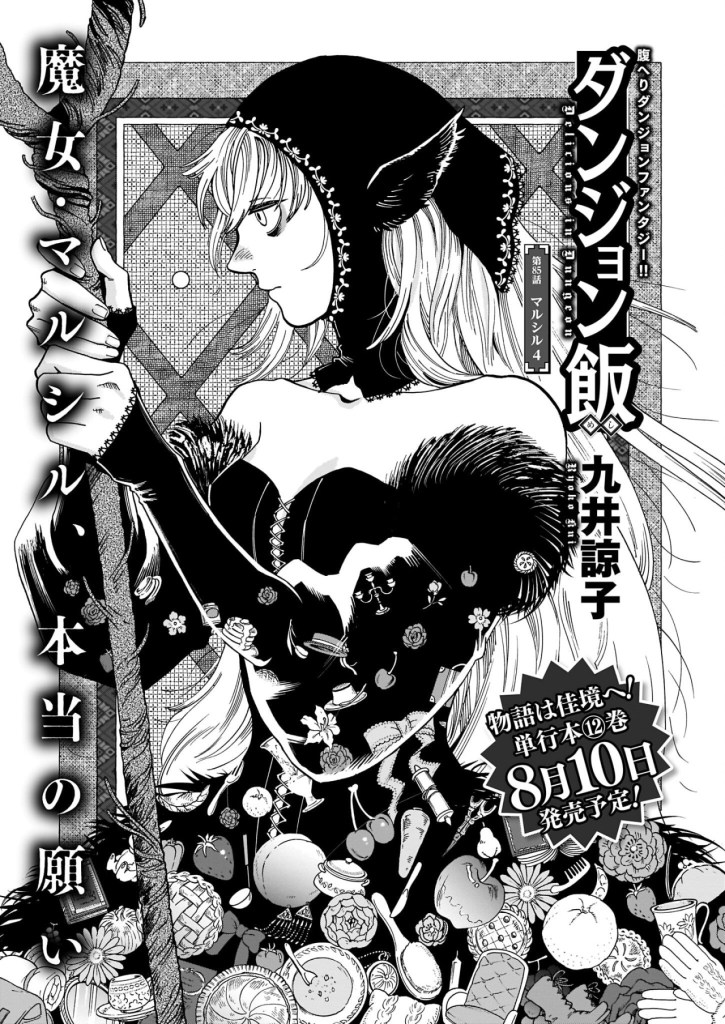

Regarding the wizard of the group, named Marcille, I must say that I’m a big fan of that whole cute face, blonde hair, braids, and choker business. Love ya Marci.

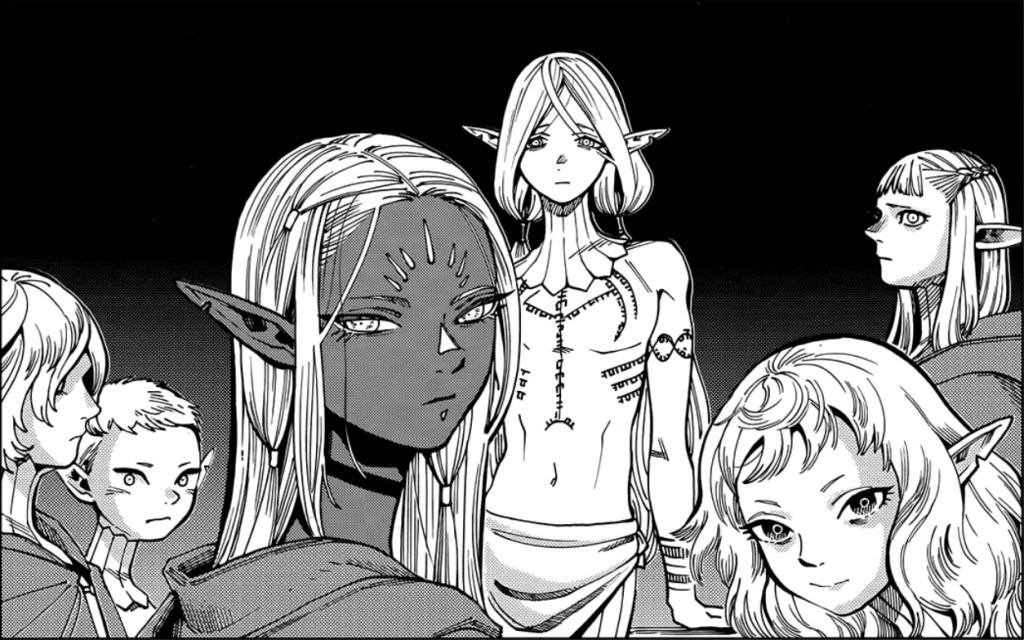

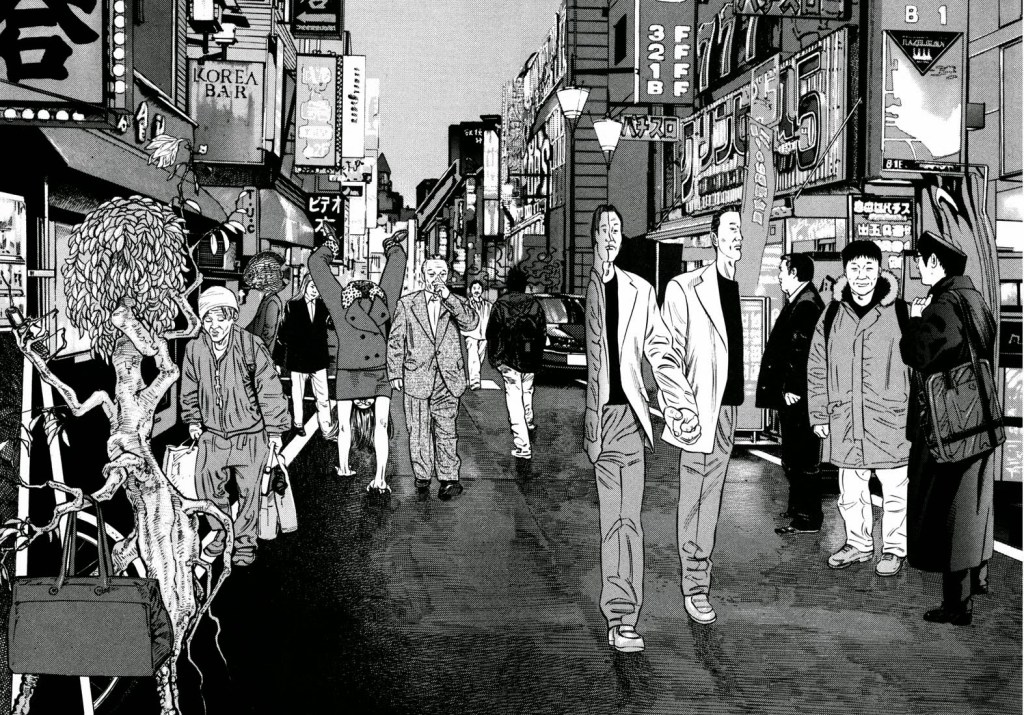

The world of this story features dungeons as prominent landmarks. At some point in history, otherworldly creatures entered the main reality and settled in underground pockets. Their wild magic created such ecosystems, filled with strange creatures and ingredients, that farming and raiding those dungeons became the backbone of entire societies. Towns have grown around them, and the first levels of those dungeons are frequented by traders and adventurers. The careful lore involving the existence and development of dungeons, as well as the political issues they caused, is one of my favorite parts of the tale (which may not be saying much, as I love most of it).

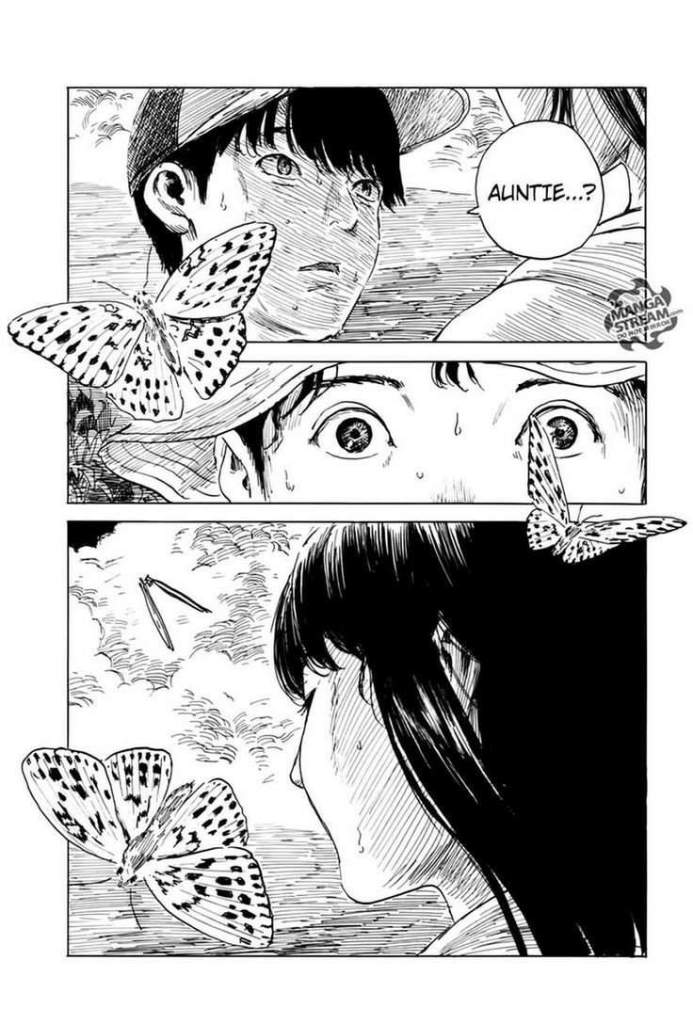

Anyway, our main group delved into the dungeon for some important reason I forgot about, and in the process, the protagonist’s sister, that laid-back sorcerer, gets eaten by a goddamn dragon. Due to the abundance of strange magic, dungeons are the only places in the world where people don’t fully die (most of the time), and some adventurers have made their trade out of following some other group and then reviving them for a reward. More ruthless groups murder other groups, then revive them for a reward. In any case, our main characters, minus the sorcerer, leave the dungeon defeated.

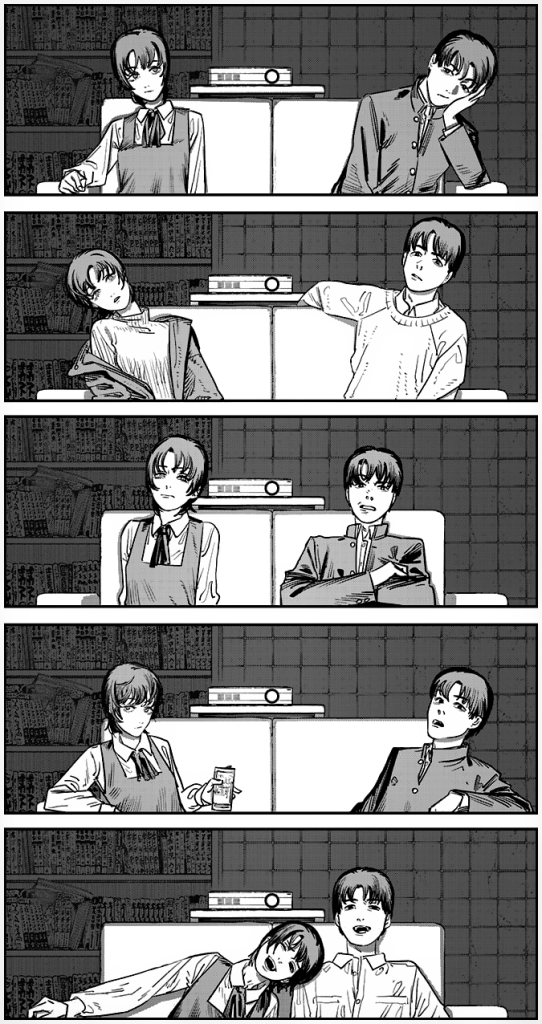

The barbarian leaves the group for a better paying gig. The main dude, that fighter whose sister is being digested, broke and desperate, decides to delve again into the depths of the dungeon to save his sibling. The uptight wizard will accompany him, because she was friends with the sister, and the rogue decides to follow them as well (I don’t recall why, but likely the promise of profit). They’re broke and can’t afford provisions, so they must survive increasingly dangerous levels by foraging and hunting the local monstrous flora and fauna, which nobody does because it’s a disgusting, horrifying prospect.

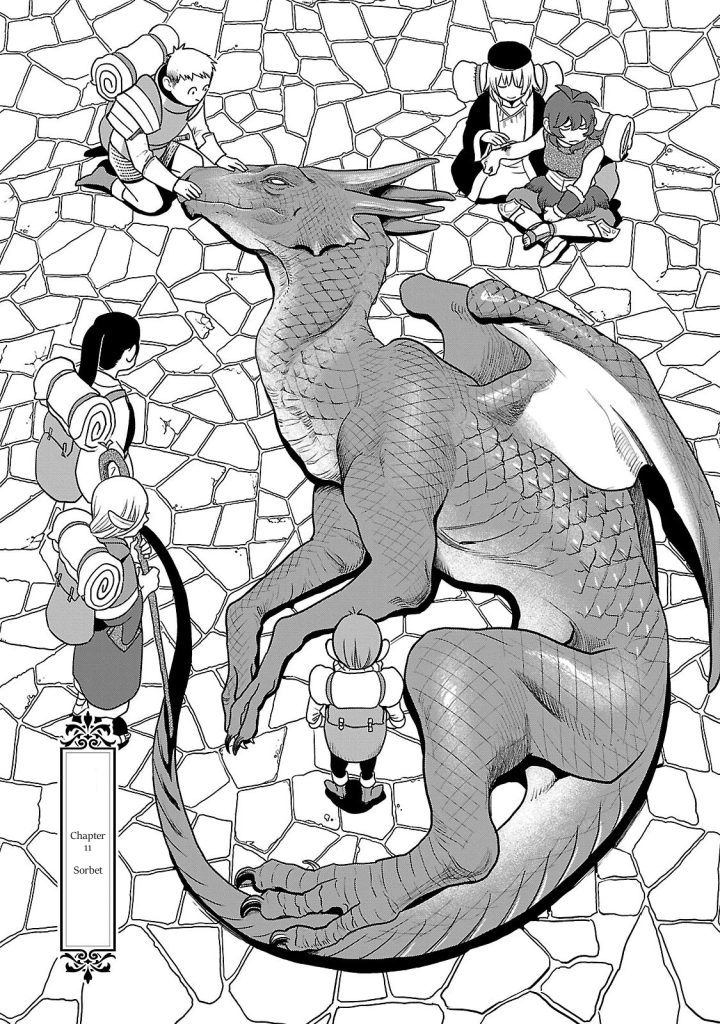

I love the concept, but this story mainly triumphs in the execution, thanks to the devoted, meticulous work of the author, a bonafide craftswoman. Lesser stories would have the protagonists win by unleashing vague, convenient powers that would overcome the obstacles, but in this tale, the author puts us right then and there with her characters as they come up with clever ways to succeed. I recall now two instances in particular: they couldn’t pass through an area plagued with carnivorous, urticant vines, so they hunted some nasty frog-like creatures whose skins made them immune to the vines, and then they skinned and wore their hides as uniforms. Dealing with untouchable ghosts, they came up with the notion of making holy water sorbet and turning it into a bludgeoning weapon. The whole story is filled with shit like this; you don’t get many tales in which the protagonists truly earn what they get.

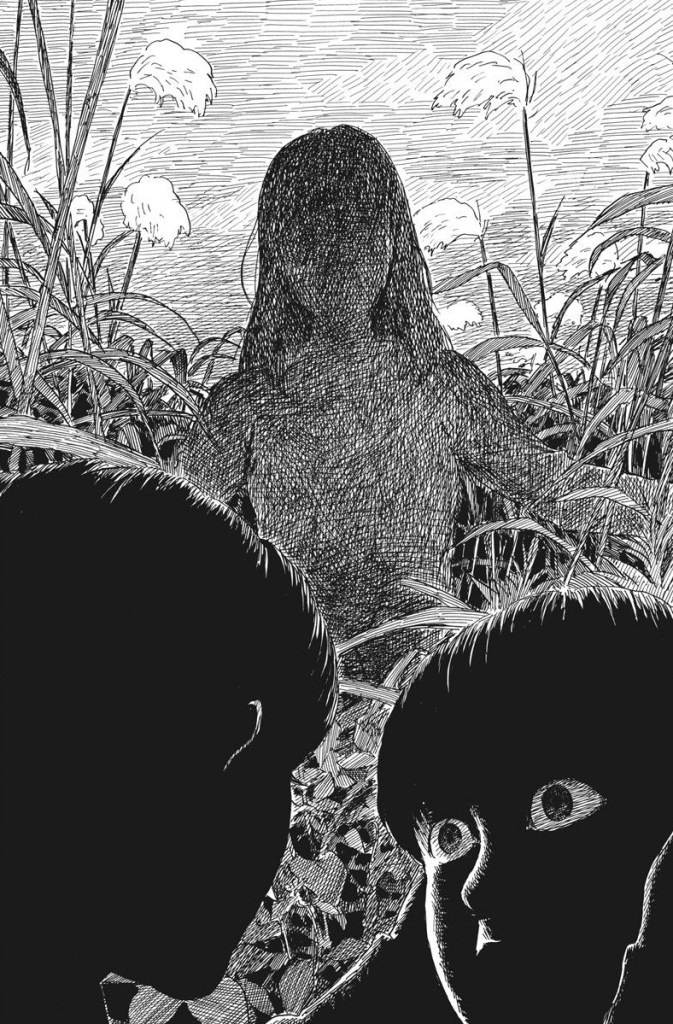

What set out to be a relatively simple tale of a group of people who don’t really get along but who end up liking each other more while trying to achieve something important, turns into a world-endangering quest in which the main characters are bound to save or ruin everything. As things got darker and darker, some of the stuff that happened, particularly the monster designs, reminded me of Berserk (which, for those who don’t know, was, for about three fifths of its run, as “peer into the abyss” as it gets).

The main group gains two new members along the way (a survivalist dwarf and a selfish cat-girl), but they also interact with other organized groups that mainly intend to hinder them. In a story with such a large cast, you could expect some significant development maybe out of the protagonist and someone else, but in this story, every main character gets a satisfying character arc, as well as some of the secondary ones. Even those who could be generally categorized as villains, and would be killed and forgotten in other stories, are treated with care and compassion by the author, who at least makes the readers understand why they’re right from their point of view in pursuing what they want.

After many wild moments and many trials and tribulations, some of which involved the main characters’ deepest pains, the story could have collapsed at the end, but it didn’t. As far as I’m concerned, the climax was brilliantly clever, and the remaining threads are tied up enough, leaving things open-ended in regards to how most of the secondary characters would progress from that point on.

I found the whole thing impeccable, a joy from start to finish. One of the best fantasy stories that I have ever experienced. If you enjoy such a setting at all, particularly if you are into D&D-like stuff, you owe it to yourself to give this a try.

The anime adaptation is in production, and will be released on Netflix. Here’s the latest trailer:

You must be logged in to post a comment.