The mansion’s front door fights back, then the servant yanks it wider and nods. I’m past him, boots on gravel, cutting for the service yard.

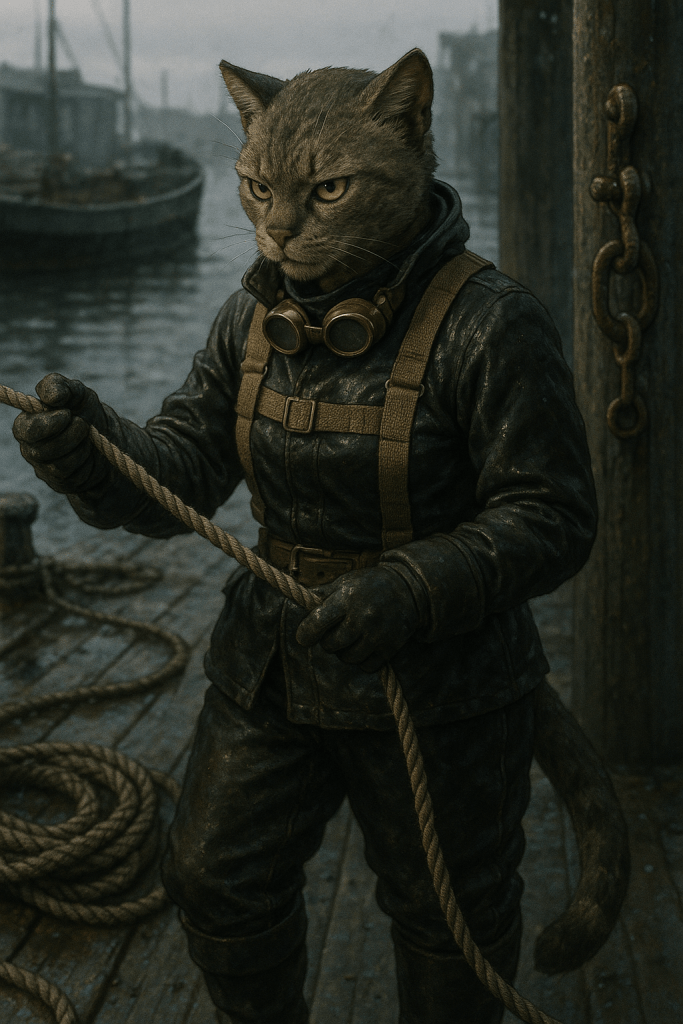

The yard’s a wedge of hard-used ground trapped between the east wing and the boundary fence—packed gravel, deep wagon ruts, built to take mud and keep moving. Our cart sits in the thick of it, and the crew’s gathered there: Pitch in his blast bib, Saffi in her dive jacket, Kestrel’s tall frame, and Hobb Rusk standing off to the side in that kiln-black Ash-Seal coat.

Past the fence, the canal runs parallel and close, separated by a narrow strip of towpath. The water’s wrong: tar-black, sluggish, filmed with a dull sheen that catches lamplight in greasy swirls. The smell reaches us in waves—sour rot with metal underneath, like wet iron left in a bucket too long.

I stop at a distance, far enough to address my crew as a group. I meet their eyes one by one: Pitch, Saffi, Kestrel.

Then I sigh. Lower my head.

My tail starts thumping against the gravel—slow, rhythmic. Old habit. I raise my gaze again, and something hardens in me.

“Alright, crew. Client’s one Lady Eira Quenreach. I had only heard of her. Now I wish it had remained that way. Had you followed me inside that trap room, there would have been far more shouting. Short version—we’re screwed. Long version—Lady was renovating her underground galleries when they dislodged an ancient artifact in a silted culvert. Messed with the seal or the ward or whatever. It started leaking that rot that has blackened the waters and made them stink something awful.”

I jerk my chin toward the canal.

“As you can see, it’s spreading far out of the estate. They reckon in two days the rot’ll be in range of the city inspectors. Of course Quenreach wants us to get rid of the artifact before someone sniffs her way. And the artifact won’t stop spewing that black shit, which means it’ll eventually ruin Brinewick’s whole canal network unless we stop it. Somehow that ain’t the worst of it.”

The silence stretches. Morning fog drifts between us, and the canal churns wrong behind the fence—thick, sluggish, a sound like something rotting from the inside out.

Kestrel laughs. Sharp. Involuntary. The sound cuts through the fog and dies fast.

I rub the fur of my brow, then meet their eyes again.

“The construction workers who approached the artifact reported pressure headaches. Fell into trance states. Got mind-wormed—intrusive compulsions toward moving water. Two workers drowned. Afterwards, all the workers quit. Some took at least a couple of the grate keys with them. A fuck-you on their way out, maybe.”

I shake my head.

“A mind-controller ancient artifact that risks rotting the whole canal network’s water. Which of course includes Brinewick’s drinking supplies. Lady Quenreach should have kissed our boots for coming down here to fix this quick.”

My jaw tightens.

“Instead, she handed me a contract that says the moment we touch that artifact, custody falls on us. Including responsibility for further contamination and deaths. And if the inspectors trace the mess back to the source and want to squeeze money out of anyone responsible, we’re supposed to pay for the protected parties’ losses—which would include the whole of Brinewick, as if we shat the ancient turd ourselves. Of course, by ‘we’ I mean me and our bossman back at headquarters. Nothing legal’s going to barrel down your way.”

I draw a breath. Let it out.

“Guess I’ve gotten through all the setup. This is the part where I tell each of you—Saffi, Pitch, Kestrel—that if you want to walk, you walk. Truth is, though, I don’t think this can be done without any of you.”

Kestrel laughs again—another sharp burst, then another, each one cutting out fast like her throat’s choking them off. Her eyes dart from me to Pitch to Saffi to the canal and back, that worried look deepening across her muzzle while her mouth keeps trying to laugh.

I turn my hands palm-up toward the sky, then drop them and force myself to meet each of their eyes one by one.

“Yeah, it was a lot to take in for me too. Let’s hear it, folks. What do you decide? I promise to shield you from any legal consequences—I’m the only one who signed, and if push comes to shove, I’ll claim I worked alone—but we’re risking more than legal here. Whoever’s staying, we gotta know soon, because we must move straight to logistics. Every minute counts.”

Pitch stands there in his blast bib, expression unreadable. Saffi’s golden eyes are hooded, slits tracking between me and the others.

Kestrel turns her head toward them both, then back to me. A broad smile spreads across her muzzle. She laughs.

“Yeah, I’m in. Not walking on this one, Jorren. You need muscle for hauling, pinning, or dragging someone out of a trance state before they drown themselves? That’s what I do.”

Another involuntary laugh bursts out of her.

“Besides, if that rot hits the drinking water and people start dying, that’s on all of us if we could’ve stopped it and didn’t. So count me in. Let’s hear the logistics.”

A sigh of relief escapes me before I can stop it.

“Don’t know how glad I am to have you by my side in this rotten mess, Kestrel.”

I turn my gaze to Pitch and Saffi.

“We got at least two old ironwork grates to crack open because their keys have flown. I’m talking thirty feet from access point to the half-collapsed culvert where the artifact is entombed, so we’ll need expert handling of bolt cutters or handsaws while mind-worms push into our brains. That’s where you’d come in, Pitch. And Saffi, intrusive compulsions toward diving into rotted flows means we need a line tender. The best in the business. The rope-meister. Not guilting you—just stating facts. We pull that artifact out of the water or soon enough Brinewick’s going to be drinking rot.”

Pitch meets my eyes directly. His voice comes out flat and certain.

“I’m in. Ironwork cracked and grates breached while mind-worms push into our heads? That’s demolition work under pressure, and that’s what I do. The rot’s real, the timeline’s real, and if we don’t stop it Brinewick’s drinking supply goes septic. So fuck the paperwork. I’ll handle the breaches. You’ve got your demolition specialist.”

Saffi’s tail curls once, then goes still. She speaks.

“You need a line tender who can read wrongness through rope before it becomes visible. Someone who won’t freeze when mind-worms start pushing compulsions. The artifact’s already killed two people. So yeah. I’ll handle the line work. You’ve got your rope-meister.”

The relief hits hard.

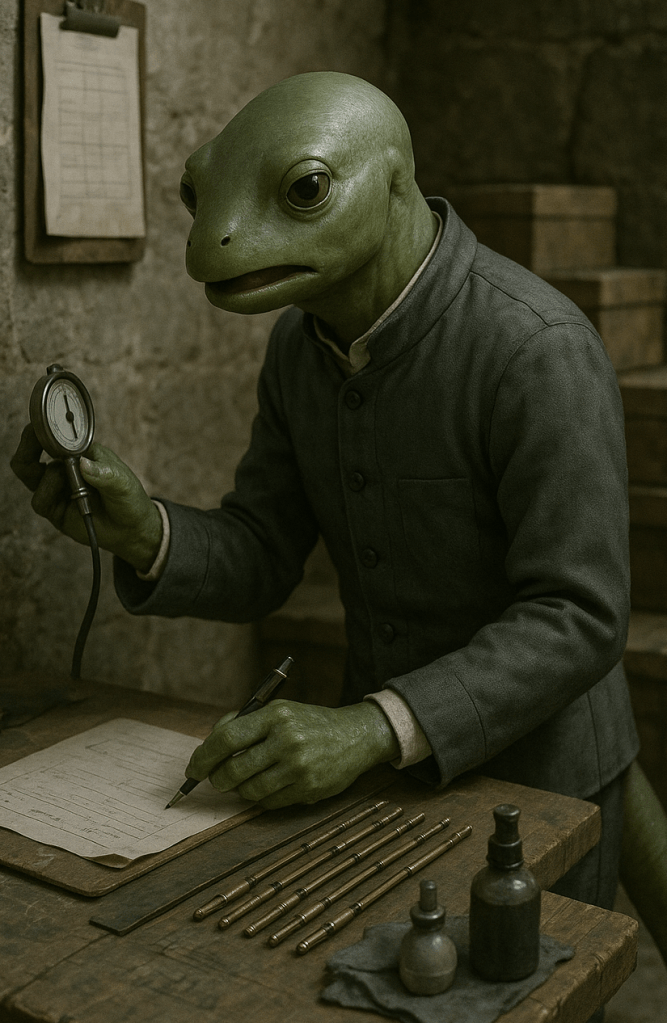

I catch movement in my periphery—Hobb Rusk stepping closer, circling around the crew’s loose cluster to position himself near our group. Still in that meticulous Ash-Seal coat, still silent, but the proximity signals engagement. Not commitment, though.

I thump my tail against the gravel once, decisively. The sound cuts through the fog and settles something in me. My face shifts—the worry-frown giving way to the harder focus I get when I’m mapping logistics.

“About thirty feet from access point to flooded section that contains our half-collapsed silted culvert and the buried artifact. Can’t wade straight to it—at least two grates we don’t have keys for. We get through the grates first. Then we dig the artifact out, slow and careful. Client believes it’s currently sealed, so we can’t risk cracking that with a quick extraction.”

I crouch down, fingers tracing an absent map in the gravel while I think it through.

“The sealed version of the artifact is already rotting the canal network and killing people, so we don’t want to know what the exposed version can do.”

The line draws itself in my head: access point to first grate to second grate to artifact location. Thirty feet of blind work underground.

“Zero visibility in those underground tunnels. Lanterns are a must.” I turn my head toward the cart. “We brought a couple. Alright, so we illuminate our steps from the access point to the grates. Imagine we’re cutting through the locked grates when mind-fuckery worms its way into our brains, telling us to dive into the canal waters. Need to be clipped to a rope, with Saffi as the anchor on the back. Anyone strays, sharp pull. These mind-compulsions don’t sound like the kind of worm you can squash easily, because construction workers just walked into a drowning—any of us starts looking loopy and tries to unclip themselves from the line, we need strength to restrain them. That’s where you’ll come in, Kestrel.”

Pitch heads toward the dredgers’ cart, his stocky frame cutting through the fog. He reaches for the bolt cutters, testing their weight and grip with practiced hands.

“I’ll take point on the grate breaches. Bolt cutters for primary cuts, hacksaw for backup if the ironwork’s thicker than expected.”

Pitch grabs the bolt cutters fully, the metal catching what little light pushes through the dawn.

“Thirty-year-old grates, no keys, zero visibility, mind-worms pushing drowning compulsions—yeah, I can work with that. Just need to know: are we cutting clean to preserve the infrastructure, or are we cracking them fast and dirty to hit the timeline? Because those are different approaches, and I need to know which one we’re buying before I start planning the cuts.”

I straighten up from the crouch, and that’s when I notice the newt-folk liaison, Hobb Rusk, standing to my side. Close—touching distance. That kiln-black coat, the ash-gray collar standing crisp despite the fog. Those large round eyes fixed on me, waiting. He’s positioned himself to hear my answer to Pitch, but he ain’t dressed for tunnels and he sure as hell ain’t volunteering to come down with us.

I meet his eyes briefly.

“Thank you for paying attention to our logistics, Master Rusk, even though I won’t even bother asking if you’re coming down to contain the artifact at the extraction point. You ain’t even dressed for it. But all we need is your magic box and a thorough destruction of the ancient terror so we can all cart back to our lives.”

I turn to face our sapper directly.

“Pitch, don’t know where you got that thing about grates being thirty years old. The way the Lady and her right-hand man sounded, the infrastructure down there is ‘ancestors-old.’ Maybe a couple hundreds of years old. Ironwork that age may be easier to saw through. Regarding infrastructure, this ain’t a ‘blow shit up’ situation, I’m afraid to disappoint. Silted culvert containing the entombed artifact is already half-collapsed—a blast may send down slabs of stone onto the artifact’s seal, then all hell’s broke loose. Lady Quenreach agrees to ruining them locked grates, just not to the point of collapsing the tunnels and fucking us all.”

Pitch moves back toward the cart and grabs the hacksaw, testing the blade tension with his thumb. His voice comes out measured.

“Ancestors-old ironwork. Right. That’s brittle, oxidized differently than modern stock—fails at different stress points. Makes the cuts trickier but maybe faster if I read the weaknesses right.”

He slides the hacksaw into his belt loop alongside the bolt cutters.

“Got primary and backup. No explosives, no structural collapse risk. Just precise cuts through old iron while mind-worms crawl into our skulls.”

A burst of wild laughter from Kestrel punctuates Pitch’s resolution. She stays quiet otherwise, that worried look still carved deep across her muzzle even as her mouth twitches toward another laugh.

Saffi moves to the cart and takes one of the hooded oil lanterns, the motion efficient and practiced.

“Alright,” I say, “both phases seem separated to me—first, clear our path to the flooded section where the artifact waits buried under two feet of contaminated water. Once we’re done with that, we head back up, leave the bolt cutters and hacksaws and whatnot, then pick up the planks and trenching shovels and block-and-tackle for the by-the-book extraction. We will enter with Pitch on point, the four of us clipped, rope-meister on the back as anchor. Let’s think perils—bad water that’s also a lure. One of us may pause, stare at the flow, step in, stop fighting to get out. Being clipped should help.”

I approach the cart to browse through the remaining tools. My hand scratches at my chin.

“Might wanna bring the throw line… but we’d have to hope the person who walked into the water wants to catch it. Rest of the risks come when we reach the silted culvert—I’m talking zero visibility sludge, confined space hazards. Two feet of water over uneven rubble is ankle-breaking terrain. Will need planks for that. And of course: crack the seal, and everyone loses.”

Saffi moves to the cart and takes a coil of long rope, looping it over her shoulder.

“Logistics of the first extraction phase look fine,” I say. “Now, worst case scenarios—imagine Saffi’s tending to the line when she suddenly decides the rotted waters look sweet enough for a dive, and we find our diver underwater in waters she shouldn’t dive in. Or what if the first one to look loopy is our gentle giant Kestrel, but nobody’s strong enough to restrain her? What if Pitch’s cutting through a grate only for his hands to drop the tools, then for him to jump pantless and ass-first into that liquid darkness? Any ideas?”

Kestrel lets out a succession of laughs that manage to sound both compulsive and nervous.

“C’mon, folks,” I say. “I’m thinking our most reasonable contingency plan is ‘don’t get mind-wormed.’ Anyone clever enough to come up with something better to do once someone’s eyes go blank?”

Pitch moves toward the cart again, reaching for one of the remaining hooded oil lanterns.

“Need light to read the ironwork properly. Can’t assess cuts or oxidation patterns in the dark.”

He takes the lantern, metal catching dull morning light through the fog.

I rub the fur of my forehead, working through the problem.

“Let me think about this… Two construction workers drowned. Plenty reported the mental compulsions but didn’t jump into the water. We need a taste of how those mind-worms actually feel like. A probe of sorts. Once we go down there—clipped of course—for the first phase, the moment one of us gets mind-wormed and starts hearing words in their head that don’t belong to them, we hurry them back up to the surface, or at least out of the access point. See how long it takes for the mind-worm to go away. Which we know it does because the affected workers all fled.”

“Alright, worst-case scenarios,” Kestrel says. “Here’s what I’m thinking—we can’t stop the mind-worm from hitting, but we can make it harder to act on. First: multiple clips on the line. Not just one carabiner—two, maybe three per person. That way if someone’s brain tells them to unhook and dive, they’ve got to fumble through extra metal while we’re yanking them back. Buys us seconds, maybe more.”

She shifts her weight, that worried look still carved deep across her muzzle even as another involuntary laugh bursts out.

“Second: watchers. We pair up—one person works, one person watches. Pitch cuts the grate, I watch his eyes. Saffi tends line, Jorren watches her. The moment someone goes blank-eyed or starts staring at the water too long, the watcher yells and we haul them out of the access point, back to the surface, see how long it takes for the compulsion to fade. Third, and this is the uncomfortable part—if the worm hits me and I decide I want that water, rope tension and crew strength might not be enough to stop me. So we need a fallback: Saffi’s line-work has to be strong enough to drag dead weight, and the rest of you need to be ready to pile on if I start moving toward the canal. Same goes for anyone else who gets wormed hard. We can’t prevent it, Jorren. But we can plan for the aftermath. Make it harder to drown ourselves even when our brains are telling us it’s the right call. Not a great plan. But it’s the only one I’ve got that’s honest about the risk.”

“Brilliant, Kestrel. Multiple clips. Pair up. I think that’s as good as it’s going to get for our first extraction phase.”

I turn my head to look up at the Ash-Seal liaison. Hobb Rusk’s standing there in that meticulous kiln-black coat, large round eyes fixed somewhere between me and the crew. He’s been listening this whole time—close enough to hear every word of our contingency planning, silent enough that I almost forgot he was there.

“Master Rusk, what exactly do you need from us? We’ve worked with other Ash-Sealers in the past but not in these fucked-up circumstances. What constraints are you relying on so you can contain the artifact in your box and pulverize it, or whatever the hell you tight-lipped fuckers do?”

Hobb’s eyes shift to meet mine directly. There’s a pause, like he’s organizing his answer into the specific order he wants. His hands stay at his sides, webbed fingers motionless. Then he speaks.

“I need the artifact intact and sealed when you hand it to me. If the seal’s cracked—if you drop it, if stone slabs crush it during excavation, if someone gets mind-wormed and drags it through contaminated water—the containment process changes completely. A sealed artifact goes into the box with standard ward protocols and salt geometry calibration. An actively leaking artifact requires layered suppression, extended calibration time, and significantly higher risk of containment failure. So your extraction needs to be precise enough that what you bring me is still structurally intact, even if it’s covered in sludge. Beyond that, I need workspace—clean ground, adequate humidity for the box’s adhesion wards, and enough light to verify seal integrity before I start the containment sequence. If you can’t provide that at the extraction site, we bring the artifact back here to the service yard before I touch it. And timeline: sealed artifact, maybe an hour for full containment. Cracked artifact, could be three to six hours depending on how bad the leak is, and I can’t guarantee success if the damage is severe enough.”

His lipless mouth compresses into a thin line.

“So the short version is this—bring me what you promised Lady Quenreach you’d extract, don’t fuck up the seal during the dig, and give me the workspace I need to do my job properly. Do that, and we’re fine. Crack it and hand me a disaster, and the timeline you’re working with collapses completely.”

I nod at Hobb Rusk, processing his parameters.

“Got it—clean ground, adequate humidity, enough light. Perfect arguments to stay topside instead of crawling through contaminated tunnels with us. Alright, we’ll bring the ancient, sludgy turd straight to your hands, and hope we don’t ruin the package along the way.”

I look around at the opulent estate grounds—manicured gardens, precisely trimmed hedges, wide gravel paths that probably cost more than my year’s wages.

“As for providing you with a good enough workspace…” I gesture at the space around us. “If the open air won’t do, we can talk to the steward. Man’s an amphibian too—maybe you two will reminisce about your family tree as you save the day.”

My tail thumps against the gravel twice. I turn to face my crew. Pitch stands there in his blast bib, bolt cutters and hacksaw collected, lantern in hand. His expression’s unreadable—that demolition-specialist look that doesn’t give away whether he’s got questions or he’s just waiting for me to finish talking. Saffi’s got her rope coiled over one shoulder and her lantern ready, golden eyes tracking between me and the others with that hooded, calculating look she gets when she’s reading group dynamics.

“Folks,” I say, “unless you’ve got some last-minute objections, let’s gear up. Nobody’s dying today. Otherwise I’ll be forced to drag you out of whatever afterlife you believe in, and that’d ruin my afternoon.”

THE END

You must be logged in to post a comment.