I need to preface this story. In December of 2024, I wrote a post about the fact that Alicia Western, the focal character in Cormac McCarthy’s last two books The Passenger and Stella Maris, had shown up in my dreams. Ever since, I’ve been haunted by her almost literally every night. Back when I commuted to and from work, the same. I close my eyes and see myself returning to that solitary patient room in the Stella Maris sanatorium. Wisconsin. 1972. Alicia Western, a unique person whom I would love to speak with even though I don’t want to speak to people in real life. Alicia, whose death, even literary, was an unbearable tragedy. Two days before she walked into the woods behind the sanatorium and let herself freeze to death.

That daydream has become my safe space. I’m beyond analyzing the psychological reasons. I just know that replaying that scene, and others that follow, brings me peace. And I need peace.

This short story plays out that initial encounter. I guess you can call it sophisticated fanfiction.

If you’re one of the two or so people who read my couple of short stories slash scenes back in mid December, about a bunch of fantasy-world dredgers, I haven’t given up on it. I’m actually working on brain damage mechanics related to suffocation and drowning. But the mechanics needed to implement are significantly more numerous and complex than I expected.

Anyway, enjoy the following short. Or don’t. I don’t care.

Half past nine at night on December 22. In two days I’ll walk into those woods behind the sanatorium and freeze to death. My mind is locked on that idea. I’ll never see Bobby again. The silence is enormous. I can hear snow falling outside.

The patient room they assigned me is in a deserted wing, away from the ones who didn’t arrive willingly. Pale green walls. Beige vinyl floor in a grid. Metal-framed bed with a striped mattress cover. The fluorescent fixture overhead casts the blue-white light of a morgue. I’m not sleepy, but I don’t know what to do with my thoughts.

The letter is still in there, half-finished. The words I can’t say while standing upright. I need to see it again—not to finish it tonight, but to verify the thing exists. That it’s real. That I didn’t hallucinate the act of writing goodbye.

I cross to the desk and pull open the drawer.

“Hello, Alicia Western. Glad to finally meet you.”

The voice is deep, male, directly behind me at the center of the room. My hand is still on the drawer handle. I didn’t hear the door. I didn’t hear anything. He spoke my full name—not “Alicia,” but “Alicia Western”—like he’s been keeping a file. Like he’s been waiting.

The Kid does that. Materializes. So do the others. This one is new. The voice doesn’t have the Kid’s circus-barker wrongness. It sounds almost… comfortable. Embodied. Purposeful. I hate that he said “glad to finally meet you” because it implies intent, duration, a plan. The visitors don’t usually speak like that. They speak in riddles or they don’t speak at all.

“You know my name,” I say. “Congratulations. That doesn’t explain what you’re doing in a locked room or why you think I owe you a greeting.”

I turn my back to him.

His voice comes again from behind me, calm and measured.

“You don’t owe me anything. First of all, I apologize—I would have preferred to infiltrate the sanatorium by acting as a volunteer. I’d engage you little by little, perhaps in the common room. But the staff would ask questions, so I had no choice but to appear in your assigned room at half past nine. I’m sure it feels violent to you. Again, I apologize.”

Turning around isn’t submission; it’s data collection. If he flinches or shifts when I look at him directly, that tells me something. If he holds steady, that tells me something else. I want to see whether his eyes track like the Kid’s do—too focused, like he’s reading lines off the back of my skull—or whether they move like a person’s.

“You say ‘violent’ like you understand the term,” I say. “Materializing uninvited in a locked room at night and speaking my full name isn’t violence—it’s theater pretending to be introduction. So let’s skip the performance. What do you want, and why should I believe you’re anything other than my own mind eating itself in a new costume?”

I turn around.

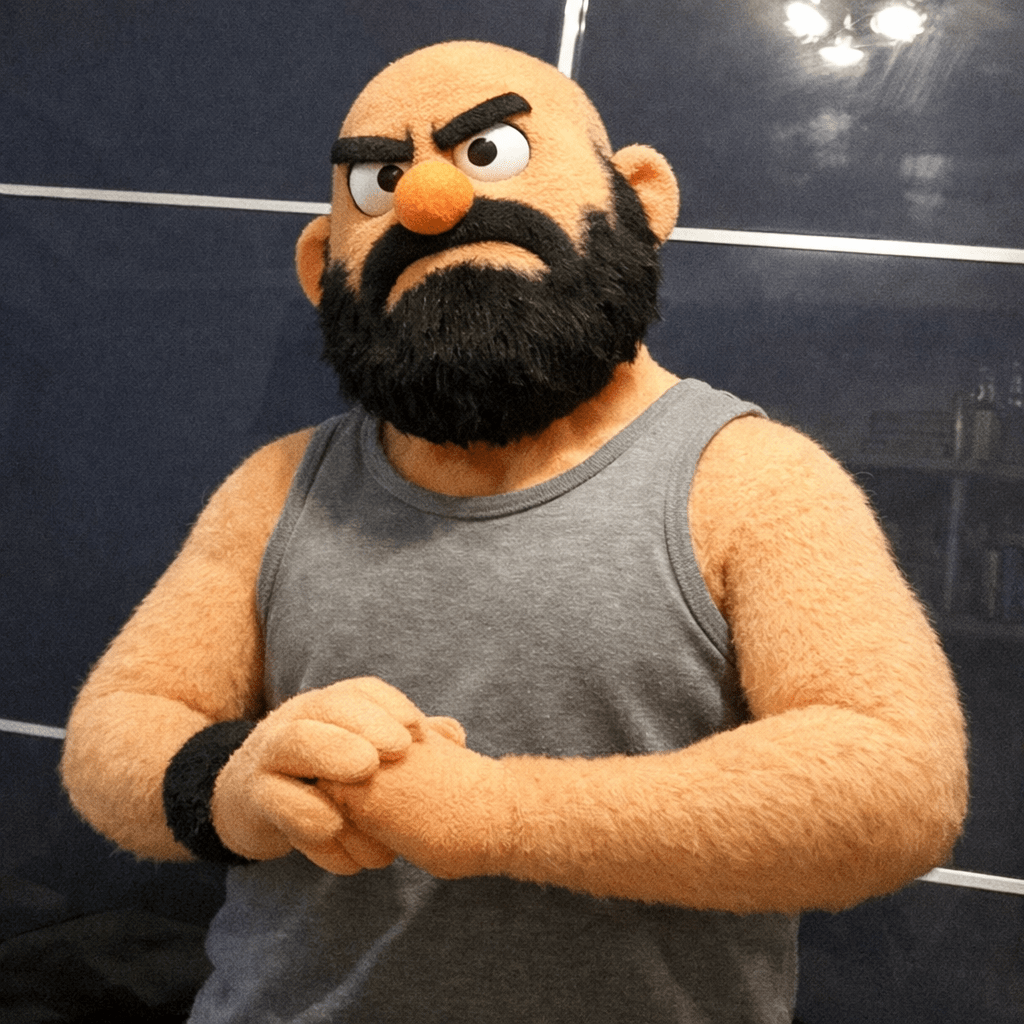

He’s tall. Very tall. Bearded, brown hair cropped short and wavy. Brown eyes, almond-shaped, watching me without the Kid’s predatory focus. A scar cuts across the bridge of his nose. He’s hulking but lean—broad through the shoulders and chest, hairy forearms visible below the sleeves of a gray wool T-shirt. Jeans, belt, sand-colored boots. He looks solid. Like he belongs in a body in a way the Kid never has.

He softens his gaze—or performs softening.

“Ah, you think I’m a hallucination. I guess that’s the most reasonable assumption for someone in your circumstances. I’m quite real, I assure you. My name is Jon Ureña. From Spain, originally. A proper introduction, less theatrical.”

Either he’s something new, a different kind of visitor with agenda and continuity the others lack, or my hallucinations have escalated to include operational security and social scripts.

I cross toward him. If he’s real in the way bodies are real, there will be tells: breath rhythm, micro-shifts in posture when I close distance, the flinch or hold that happens when someone’s personal space gets violated. If he’s an eidolon, the space between us might behave differently. The Kid sometimes feels like he’s projected onto the room rather than standing in it, like depth perception doesn’t apply correctly.

I cross toward him. He just watches me close the distance until I’m near enough to feel the heat coming off his chest.

He’s warm. The smell is there: musk, faint sweat, the scent of a body that’s been wearing clothes all day. His breathing is steady, audible at this range. He looks down at me, calm, unbothered.

“Take all the time you need to react to the sudden presence of a stranger in your locked room,” he says.

Either he’s solid or my visitors have learned to simulate flesh convincingly. The Kid never felt like this—the Kid is hyper-real but frictionless, rendered rather than present. Jon Ureña has mass.

I place my hands on his chest.

Muscle shifts under the cloth. His heartbeat is there, palpable through the wool and skin. The rise and fall of his breath. Ribs expanding. All the micro-mechanics of a body that actually inhabits flesh.

“I assure you, Alicia Western, that I’m real as you are,” he says quietly, still looking at me.

I’m done collecting data through touch. I step back.

He nods at me.

“Alright. My solid presence established then. Shoot away. Your questions, I mean. To the stranger who just showed up in your assigned patient room at half past nine.”

He’s inviting interrogation. Like he’s waiting for me to ask the obvious questions. The eidolons don’t do this; they don’t invite sustained questioning or stand around waiting for me to process their arrival.

The desk drawer is still half-open. My letter to Bobby is inside—unfinished, hidden under the prayer book. If he’s been watching, he’ll react when I reach for it. I pull the drawer fully open.

“I worry about your state of mind,” Jon says, calm and measured. “About whether we even can hold this conversation. But I came at this point because you needed to feel in your bones the danger of the situation.”

The prayer book is there, edges worn. I lift it. Beneath it, the folded letter—sheets of lined paper, blue ink, my handwriting. I take it out slowly, deliberately, watching his face.

“That’s your goodbye letter to Bobby, isn’t it?” Jon asks. “I suspect you haven’t finished it yet. I have the finished version. In case you want to read it.”

That’s impossible unless he’s been in this drawer before, or unless this is my unconscious serving up its own completion fantasies through a convenient mouthpiece. If he has a “finished version,” that means he’s claiming foreknowledge of what I’ll write in the next two days.

I unfold the pages slowly, eyes scanning the handwriting without looking up at him.

The text reads:

December 22, 1972

Stella Maris

Bobby,

The probability of you reading this approaches zero. The doctors said “braindead”—past tense, declarative, clinically certain. But I cannot pull the plug. I fled instead. So this letter exists in a superposition state: written but unread, meant for you but addressed to no one. Schrödinger’s goodbye.

If you are reading this, then something impossible happened. You woke up. The substrate repaired itself against all medical prediction. In which case, you should know: on the 24th—Christmas Eve, because apparently I have a taste for symbolic timing—I intend to walk into the woods behind the sanatorium and let the Wisconsin winter finish what Lake Tahoe started.

I am trying to explain this rationally, but the premises keep collapsing: Premise One: You were my only tether to continued existence. Premise Two: Without you conscious in the world, the equation no longer balances. Conclusion: Death is the optimal solution. But even I can see the flaw in my logic. I have spent twenty-two years analyzing everything except the one variable that matters: that I want to die has been true longer than you have been in a coma. The coma is just the excuse my mind has been waiting for.

You used to take me to that bar in Nashville. Jazz on Thursdays. You would order whiskey and I would watch the colors the saxophone made—ambers and deep golds, spiraling up into the smoke. You never tried to fix me during those nights. You just sat there, let me talk about Gödel or Cantor or whatever mathematical dead-end I was pursuing that month. You listened without needing me to be different. I miss that. I miss you. I miss my brother so much it aches behind my ribs.

There are things I need you to know, in the infinitesimal probability you are reading this: One: None of this is your fault. I know your patterns, Bobby. You run when things hurt, you isolate when you cannot fix something, and if you are reading this you will spend the rest of your life—

The sentence ends there. Mid-thought. I couldn’t figure out how to complete it without collapsing into accusation or apology, and Bobby deserves neither. So I stopped.

I fold the pages slowly and look up at Jon.

He’s still standing there, patient, watching me with that same unbothered calm. The silence stretches between us—sepulchral, nothing but the ghost of snow falling outside.

“Would you like to receive the finished version of the letter you’ve just read? Now that your unfinished letter is fresh in your mind…”

He produces a folded letter as if he had been holding it this whole time. The letter is yellowed, creased, the paper aged in a way that takes years. He extends it toward me.

I take it.

Either he’s claiming time travel or he’s claiming he excavated this letter from some future archive where my suicide is historical fact and someone kept the letter long enough for it to age like this. Or it’s theater. My unconscious generating set dressing to make the artifact feel canonical.

I unfold it carefully. The handwriting is mine. Same blue ink. The date reads December 22, 1972—today. It starts the same way: Bobby, The probability of you reading this approaches zero…

But it doesn’t stop where I stopped.

Past the mid-sentence break. Past “you will spend the rest of your life—” and into believing you should have prevented it somehow. You could not have. This was always the trajectory.

The letter doesn’t stop where I stopped. Seven numbered confessions. One: None of this is your fault. Then Two: I deliberately left Granellen behind without saying goodbye. Then Three: I died a virgin. Twenty-two years old and I never let anyone close enough.

I stop breathing.

That thought—virginity, the loneliness of never being touched with tenderness—I had that thought yesterday. Sitting in the common room watching the nurses move through their rounds. I didn’t write it down. I didn’t tell anyone. It was just there, in my head, sharp and private.

Four: The inheritance money from Grandfather—you bought that race car and crashed it in Italy and ended up braindead, and I cannot even be angry at you for it because at least you lived before the crash.

Five: Sometimes I just wanted to buy groceries with someone and argue about peaches.

The domestic fantasy I’ve never said aloud. That exact phrasing—”argue about peaches”—that was mine. Three days ago, lying in bed, imagining a version of myself who got to have small, ordinary arguments in a kitchen somewhere.

This isn’t guessing. This is extraction.

I scan ahead. The letter continues through numbered confessions—mathematics failing me, lying to my therapist, testing whether he’ll notice inconsistencies. Then the closing lines: The woods are waiting. December 24th. Christmas Eve. I love you. I am sorry.

And a postscript: I remember every word you ever said to me. Every single word. Most people forget. I would give anything to forget. But I cannot. So I am taking all of it with me.

That’s mine too. The burden of remembering every conversation with Bobby, every word, archived and immutable.

I lower the letter slowly.

“I assume you’ve recognized your thoughts in the finished version,” Jon says quietly. “One you have yet to write. What questions arise in your mind?”

I fold the pages and look up at him. Jon watches without speaking.

He sighs.

“Don’t just look at me like that, Alicia. C’mon, girl. Surely you have plenty to ask this stranger who showed up in your locked room with a letter you’ve yet to finish.”

The real question isn’t how did you get this or are you a time traveler. Those are diagnostic dead-ends. The real question is tactical: why show me the completion now, two days before December 24, in a locked room when no one else is listening? If he wanted institutional intervention he could have brought staff, triggered a psychiatric hold. If he just wanted to document he could have waited until after and collected the letter from my body. Instead he’s here now, with the finished version, waiting for me to react like my reaction is the variable that matters.

He thinks confrontation will trigger something. Shame, maybe. Or survival instinct. Or he thinks seeing the letter completed—reading my own probable ending—will make the plan feel real enough to collapse it.

It doesn’t. Bobby’s still gone. December 24 is still two days away. The equation hasn’t changed.

Jon watches me not answering, then sighs again—deeper this time, tired.

“You’re a hard one. Okay, maybe I’m asking too much of you in these circumstances. At the end of your road. Let me clarify what I’m doing here: I was told about you by someone you know well. A certain Bobby Western. He asked me to come and prevent the silly thing you intend to do in a couple of days.”

That’s the move. The lever he thinks will work.

If Bobby sent him, Bobby woke up—contradicting braindeath. Either the doctors were wrong or this is my unconscious staging wish-fulfillment: Bobby alive, Bobby knows, Bobby sends help.

Elegant. Also suspect. Because Bobby’s in Italy, braindead, on a ventilator. The last time I saw him his eyes were open but empty and the neurologist used the word “irreversible” three times in one sentence.

Either way, I need to hear what comes next.

The silence stretches. Jon watches me. Then something shifts in his expression—concern bleeding into impatience.

“Beautiful as your face is, it’s also quite unreadable at this point of you barely holding on to your life. Alright, I’ve got a couple of photos of Bobby post-coma. But you’ve got to ask for them, Alicia. I can’t be doing all the work here.”

He wants me to make myself legible as someone who needs proof. If I don’t, he keeps the photos and I stay in this loop.

I let the silence sit.

Jon stands there observing me. The impatience fades from his face. His eyes soften. Then he steps closer—closes the distance himself without asking permission—until he’s at touching range. Both of us silent now. Him looking down at me. Like proximity is supposed to do the work words couldn’t.

Real urgency can’t tolerate this much silence; people start offering evidence unprompted. But there’s a third option. I reach out and hold his hand.

Solid. Much bigger than mine. He just lets me hold it, the contact easy and unbothered. Then he leans in and presses his mouth softly to my forehead.

“This nightmare is ending, Alicia,” he says against my skin. “You don’t need to walk into those woods anymore.”

I squeeze his hand. Acknowledgment. The gesture saying: I’m still here. I’m listening. Show me.

Jon reads it. He produces a photograph and hands it to me.

“Well, here you have it. After Bobby woke up from his coma and the goddamn Italians let him call home, your grandmother told him that you had killed yourself. I think you can imagine… the state in which that put him. I haven’t asked what he did from 1973 to 1979. I assume he was handling grief poorly. When he resurfaced, he joined a salvage team. A man has to earn his keep even when the world has stopped turning.”

I look down at the photograph in my hand.

A group of men standing on a riverbank. Salvage-diving gear—dark rubber suits, tanks. Bobby’s there among them. Mid-thirties, which would be right for 1981 if he lived that long. Someone wrote ’81 in a corner in what looks like ballpoint pen.

But it’s his face that stops me.

I know that face. Every angle, every microexpression, the exact geometry of how he holds his mouth when he’s trying to look functional. And even in a work photo—surrounded by colleagues, probably taken to document the team—he looks haunted. Like he’s doing his best to appear normal while something unbearable churns beneath the performance. The kind of expression you only recognize if you’ve seen someone try to hold themselves together when the internal architecture is compromised.

Specific, inescapable grief.

He’s alive in this photo. Standing upright on a riverbank in 1981, nine years from now, working salvage with people who probably have no idea what he’s carrying. Which means the neurologists were wrong. “Irreversible braindeath” became reversed. The substrate repaired itself. Bobby woke up.

In his timeline, I’m already dead. And he spent years—1973 to at least 1981, maybe longer—living with that. Carrying it. The haunted look in this photo isn’t just grief; it’s the specific weight of believing your sister walked into the woods because you weren’t there to stop her.

But I’m standing here holding proof he survived. Which means December 24 just became obsolete. Not because someone talked me out of it. Because the premise collapsed. Bobby’s awake. The equation rebalanced. I don’t need to walk into those woods anymore.

I keep staring at the photo. Jon waits. Then his hand moves. Gentle. He brushes a stray lock of hair behind my ear, the gesture easy and unbothered, like it’s the most natural thing in the world to stand in a patient room at half past nine and tend to someone’s appearance while they’re holding evidence that rewrites their entire operational logic.

“That photo is from 1981,” Jon says, voice calm and measured. “I was born in 1985. I met Bobby by coincidence in 2006, in the Balearic Islands, off the coast of Spain. Formentera, specifically.”

Thirty-four years from now.

Jon’s hand withdraws from mine—not abruptly, just a natural release, like he needs distance to deliver what comes next.

“I’m a bit of a blabbermouth about the past,” he continues, “and your brother, that by then was a taciturn man with a full head of gray, nursing his drink at the same beach bar, was listening to me talk about the Roman Empire.”

Bobby would be sixty in 2006 if he lived that long. Jon’s describing a version of my brother I’ll never meet—decades older, silent, carrying thirty-four years of whatever happened after this moment.

“You want to know how the story continues?” Jon asks.

I look up from the photo. Meet his eyes. Brown, almond-shaped, watching me without the Kid’s predatory focus. Just waiting to see whether I’ll give him permission to keep talking or whether I’ll shut him down.

If he’s real and telling the truth, then Bobby survived long enough to care in 2006, and had access to someone—something—capable of sending intervention across thirty-four years. If he’s an eidolon, this script is new: time-traveling guardian with photos as evidence, tactile solidity, and a willingness to wait for me to vocalize interest instead of just performing his monologue and vanishing.

“Yeah. Tell me how you met my brother three decades from now.”

Jon smiles like I just gave him exactly the opening he was hoping for.

“Alright, Alicia. Picture this: your brother and I are on that beach in Formentera. He had approached me as I walked away from that beach bar, where I had discussed the Roman Empire with a history professor. Your brother had a strange expression in his grief-lined face. As if he intended to do something absurd, but the problem he had been burdened by for decades required a very specific miracle.”

Jon’s voice shifts—takes on the quality of someone settling into a story he’s told before, one he knows by heart.

“He said in a dry voice, ‘You speak about the Romans as if you knew them personally.’ I admitted it—I don’t care if people find out I’m a time traveler. If they don’t believe it, fuck them. He kept looking at me with these intense eyes. Then he asked, ‘Can you travel to December of 1972?’ I shifted my weight. I recognized the pressure, the urgency. This was a man who needed something to be set right. I said, ‘Yes, no problem. For someone’s sake, I’m guessing. What do you need? What should I do?'”

Jon pauses. Watches my face. Then delivers the last line quietly, like he’s handing me something fragile.

“He said, in this faint voice, as if he could barely form the words—’Save my sister.'”

The timeline makes no ontological sense unless time travel is real or unless this is my unconscious staging the most elaborate wish-fulfillment hallucination I’ve ever produced, complete with thermal signatures and completed letters and a stranger who kisses my forehead and tells me Bobby asked him to save me.

Either way, I just spoke—actually vocalized interest instead of stonewalling—which means I’ve already decided to let this play out instead of dismissing it as theater.

Jon’s expression warms like I just gave him permission to continue.

“Over the next few days, your brother told me about you. A hauntingly-beautiful math genius. Synesthete. Haunted by visions herself. Who abandoned math because it was driving her mad…” He pauses, then adds, almost sheepish, “Well, I’m not entirely sure why you abandoned math. I’m not a math person myself. Anyway, he showed me a photo of yourself, so old and yellowed at that point. He didn’t part ways with it.”

Yellowed. Carried for decades. Bobby holding onto a photograph of me the way someone holds onto evidence of a person who stopped existing. The grief in that action—preservation as mourning ritual—is a thing Bobby would do. Keep the artifact. Never talk about it. Just carry it.

Jon’s voice drops, becomes quieter.

“Your brother made it very clear that you’re a unique being and that your passing from the world was a horrifying tragedy. So, I investigated your circumstances in 1972, found out what patient room you were staying at, and I’ve come here tonight to ask you—please, don’t kill yourself, Alicia Western.”

He steps closer. Both hands come up and settle on my shoulders—firm, grounding pressure, like he’s trying to anchor me to the room while delivering the rest.

“There’s plenty more for you to experience out there. Even happiness.”

Like it’s a fact instead of a sentimental projection. Like Bobby told him I deserved it and Jon believed him.

I need a moment to let the information settle. Not stonewalling—just processing whether this timeline makes ontological sense or whether I’m watching my mind eat itself in a new costume.

Jon stands there, hands on my shoulders, waiting. His breathing is steady.

The silence stretches. I can feel his pulse through his palms—steady, unhurried. Real people with real errands usually can’t tolerate this much silence. They elaborate. They justify. They offer more proof.

“It’s a lot to take in, for sure,” Jon says. “What are you thinking?”

Bobby’s alive. Woke from the coma. Survived being told I killed myself. Lived long enough to care in 2006 and find someone who could reach backward across decades to intervene. Which means the premise—Bobby gone, equation unbalanced, December 24 necessary—just collapsed. I don’t need to finish the letter or tie a red sash or find a tree far enough into the woods.

If this is real, then I owe him acknowledgment—not sentimental gratitude, just recognition that he came here and did what Bobby asked. If this is hallucination, then my unconscious is staging the rescue it wants and I should let it play out instead of stonewalling.

His hands are still on my shoulders. I reach up and place mine on his own shoulders—steady contact, protective gesture returned, acknowledgment that he crossed temporal distance to deliver this and I’m not dismissing it.

He shifts his stance slightly. One hand slides from my shoulder to my waist—the contact more intimate now.

I meet his eyes.

“You just told me my brother lived to sixty. That he survived the coma, the grief, decades of carrying my death, and still cared enough to send you backward to prevent it. If that’s true—if Bobby’s really out there, conscious, alive—then you’ve already done what you came for. I’m not walking into those woods anymore.”

Jon’s face breaks into a smile—genuine warmth, relief flooding his expression. Then he wraps me carefully in his arms, my frame enclosed in his solid, muscular body. The hug is enveloping, protective, like I’m something that needs holding together.

“I’m so glad to hear you say that, Alicia,” he says against my hair. “You don’t have to be alone until Bobby wakes. I can bring stuff from the future, other timelines… As a time traveler, I have damn near infinite access to money. I’ll make sure that you and your brother never have to worry about money ever again.”

He closes his arms tighter. But I didn’t authorize this hug. He initiated and closed his arms and I’m inside the gesture before I decided whether I wanted it. Which is tender, yes, and protective, yes, but also presumptive. I need space to think without being held like a rescued animal.

I step back carefully—gently, because he did just cross thirty-four years to prevent my death and that doesn’t deserve hostility—and put an arm’s length of distance between us.

Jon’s arms release easily. He just watches me, unbothered.

“I appreciate the intervention, Jon. And the financial offer. But I need you to clarify something—when you say I don’t need to be alone until Bobby wakes up, what exactly are you proposing? Are you planning to stay here in 1972, or are you offering periodic visits across the timeline, or is this just about making sure I have access to resources?”

Jon laughs softly, then scratches the back of his neck—a sheepish gesture, almost apologetic.

“Yeah, I haven’t explained much of anything, have I.” He drops his hand. “I don’t rely on technology to travel in time. It’s something I can do—something different in my brain. I’ve never met anyone else like me. I can bring objects with me across the time jumps, but I can’t bring any living thing.”

He pauses, and something shifts in his expression, bleeding through the careful explanation.

“That’s my… personal loneliness that I’ve endured for a long, long time. Nobody has figured out why, but whenever I try to bring anything alive, from people to even bacteria, it just stays behind. So I can’t bring you to other timelines, to the future or whatever. I meant literally accompanying you, filling the loneliness so to speak, until your brother wakes up at the latest on April 27, 1973.”

That’s not just intervention—that’s relationship.

“Alright,” I say. “So you can’t bring me to other timelines, which means ‘traveling together’ means you staying here in 1972 and we spend December through April in the same timeline, conventional sequence. That’s what you mean by ‘accompanying me’—physical presence, not periodic visits. But you still haven’t explained the plan. What are you actually proposing to do about Bobby? Are you just telling me he wakes up in April, or are you intervening somehow to make sure he wakes up? And what does ‘traveling together’ look like day-to-day—are you staying here in Stella Maris, getting a room nearby, or leaving and coming back? I need the operational picture before I agree to anything.”

Jon’s face clears like I just asked exactly the right question.

“I see you need details, and I’m happy to give them.” He takes a deep breath. “I had thought of the following: you leaving Stella Maris as soon as possible. Getting the fuck out of Dodge. Buy you some clothes, as I know you’ve given away all your possessions. Then, we buy a mansion somewhere you prefer. I’ve scouted some, and tested in other timelines that they can be bought at a short notice. If you think of specific places in which to live, just tell me and I’ll scout more.”

A mansion. Not a hotel room, not temporary housing—a property he’s already scouted across timelines to confirm availability. Which means he’s been planning logistics before he even materialized in this room.

“Once we own that base of operations, so to speak,” Jon continues, “we call the goddamn Italians, tell them we’re coming. I pay them for the treatment to Bobby, and add a generous donation for not pulling the plug. Then, we extract Bobby out of there. We fly him in a private flying vehicle from the future back to our mansion. There, we move Bobby into a special bed designed for coma patients. It’s controlled by artificial intelligence. Actually, one named Hypatia, whom my company developed. She’s fantastic, you’ll see. This bed can move the muscles of the comatose patient to avoid atrophy, it can turn them when needed to prevent sores…” He’s warming to the explanation now, more animated. “And it comes with a neurological scanner of sorts that tells us how his brain reacts to stimuli even in his dreams. You see, we haven’t figured out in the future how to wake comatose patients up from their comas, but we’ve proven scientifically that using the kind of treatments that the bed provides, they wake up even sooner, so we may not have to wait until April 1973.”

That’s not companionship—that’s moving Bobby across an ocean and buying me a mansion. Bobby physically present in the same location as me instead of vegetative in Italy while I wait alone in Wisconsin.

The plan has structural coherence—if Jon can bring objects across timelines, a medical bed and aircraft make sense. If he has infinite money via temporal arbitrage, buying a mansion and bribing Italians is trivial. If Bobby’s substrate can recover—the photo proves he does—then better medical support could accelerate that recovery.

But the plan also means I’m making a choice right now. Not just “don’t kill yourself on December 24” but “leave Stella Maris, accept Jon’s material patronage, live in a mansion he buys, cohabit with a comatose Bobby and a time traveler I met twenty minutes ago, and wait for Hypatia the AI to tell us when Bobby’s brain is waking up.”

And he’s standing there, waiting for me to respond to the plan like it’s a done deal. Like of course I’ll say yes because Bobby and mansion and infinite money and accelerated recovery timeline.

But I need to think about what saying yes actually means. I’d be leaving the only institution I chose voluntarily. Entrusting Bobby’s physical body to technology I haven’t verified. Cohabiting with Jon for an indefinite period—December to April minimum, possibly longer if the bed accelerates things or doesn’t. Accepting financial dependence on someone I literally just met who claims to be from 2006 and says my sixty-year-old brother sent him backward to save me.

If he’s real, that’s rescue. Bobby’s alive and I owe him the chance to prove the bed works. If he’s an eidolon, this is my unconscious staging the most elaborate wish-fulfillment scenario it’s ever produced—Bobby conscious, infinite resources, companionship, medical intervention, escape from Stella Maris—and saying yes means I’m letting the hallucination dictate my material decisions. Which is how you end up sectioned permanently.

But the photo was real. Thermal ink, grain, Bobby’s face in ’81. The letter was real—yellowed paper, my handwriting, thoughts I recognize. His body is real—heartbeat, musk, solidity. So either he’s real, or my visitors have escalated to full sensory simulation and I can’t trust perception anymore. Which means I’m already lost.

If I can’t trust perception, then it doesn’t matter whether I say yes or no—reality is contested either way. But if he’s real, and I say no, then Bobby wakes up in Italy in April and I’m still here in Stella Maris having refused the intervention. December 24 is still on the table because the equation hasn’t changed, just the timeline. Whereas if I say yes, Bobby’s here. Jon’s here. The bed is here. And I’m not alone while waiting for Bobby to wake.

That’s the variable that actually matters. Not the mansion or the money or even the medical tech, but that I wouldn’t be alone. I’ve been alone since I fled Italy. Alone in the patient room. Alone with the visitors. Alone with the letter and the woods and December 24. Jon’s offering to end that. Not with platitudes or therapy or medication, but with physical presence and operational logistics and Bobby in the same house. If he can actually deliver that, then yes is the only answer that makes sense.

I need to confirm he understands what he’s offering—that this isn’t just “prevent suicide and leave,” it’s “stay until Bobby wakes and possibly longer, cohabit with a woman you just met who has visitors and doesn’t do community and will test whether you’re real by seeing if you sustain tenderness or start trying to manage her.”

“I’ll leave with you,” I say. “We’ll set up the mansion, extract Bobby, try the bed. If Hypatia can actually monitor his neural activity and the bed prevents atrophy, that’s better than leaving him vegetative in Italy while I wait here.”

Relief floods through Jon’s face.

“But I need you to clarify something before I agree to the whole operational picture,” I continue. “What do you actually want in return for all of this? You’re offering infinite money, a mansion, future-tech medical equipment, and your continuous presence for months. Nobody does that without expecting something. So what is it? Companionship? Gratitude? Proof that the mission succeeded? Or something else you haven’t named yet? And when you say ‘traveling together,’ do you mean you’re staying the entire time—December through whenever Bobby wakes—or are you setting everything up and then leaving, or checking in periodically? I need to know what kind of relationship you’re proposing before I let you restructure my entire material reality.”

Jon meets my eyes. Something shifts in his expression—the careful explanation dropping away. What’s left is plainer.

“Are you subtly asking me if I want to fuck you, Alicia? Is that the concern? Any heterosexual man would want to be intimate with you. That doesn’t exclude me. But you are in an extremely vulnerable emotional situation. I wouldn’t think of even going along those lines until you are settled, feel better, and genuinely feel something in terms of reciprocity.”

He’s acknowledging the power differential. Naming it instead of pretending it doesn’t exist.

“I also get lonely, Alicia,” he says, quieter now, “and most human beings across the vast spans of time are unbearably, painfully boring. I want to spend time with someone special. Travel together, watch movies, have interesting conversations. Buying you a mansion and getting Bobby out of Italy isn’t much of an effort when you have my kind of money.”

That’s honest. Not manipulation masked as rescue. Just stating the operational picture clearly—intervention plus optional intimacy, my timeline, my choice. The real ask is companionship—time with someone special, movies, conversation, mutual loneliness addressed.

The plan makes sense. Leave Stella Maris, set up infrastructure, extract Bobby, cohabit until Bobby wakes. Companionship optional but available if I want it. Intimacy deferred until I initiate. I don’t need to be alone while waiting for Bobby to wake up if Jon’s offering to stay and the offer is genuine.

“I accept. We’ll leave Stella Maris, set up the mansion, extract Bobby, install him in Hypatia’s bed. You can stay if you want—companionship, movies, whatever—but I’m not promising anything beyond cohabitation until I see whether you’re real across ordinary time. And if at any point this starts feeling like management instead of companionship, I’m walking. Understood?”

I close the distance between us. Not invasively. Just reducing the conversational space I created earlier. He doesn’t retreat. Just stands there as I approach. At this range I can feel the heat coming off his chest again. See the rise and fall of his breath.

He smiles at me—warm, unbothered.

“That’s great, Alicia. Then it’s on your terms when you want to leave Stella Maris. I know you came voluntarily, but I guess you want to say goodbye to people here. Whenever you’re ready, you’ll just have to call me on the transmitter, tell me to come get you, and I’ll show up with a car, ask the receptionist whether Alicia Western is here. I’ll play the part of someone from your past who came to take you away from this… well, sad place. About intimacy, you don’t need to promise anything nor even think about it. Just focus on returning back to life. But regarding what you said about ‘if at any point this starts feeling like management instead of companionship, I’m walking’… I’m not sure I understand. What would management look like to you?”

His hand comes up. Fingers brush against my cheek—soft, deliberate, the gesture tender but also presumptive. Like he’s allowed to touch my face while asking me to define boundaries. That’s proximity I initiated by moving close after accepting the plan provisionally, yes—but it’s also proximity that’s starting to feel like it’s assuming the relationship is already defined when we’re still clarifying what the relationship actually is.

I need space. His heat, his smell, his hand on my face—it’s all too close to think clearly. Better to step back now. Create conversational distance again. Signal that I’m considering the offer seriously but I need room to articulate what I actually need without his touch as variable. If he respects the boundary adjustment, that’s a tell that he meant what he said about “on your terms.” If he closes distance again immediately or looks hurt, that’s a different tell—means he needs proximity to feel secure, which would be its own kind of dependence I’d need to account for.

I step back. His hand falls away from my cheek.

“Management looks like you deciding what’s good for me and then engineering circumstances so I arrive at that conclusion on my own while believing it was my choice,” I say. “Companionship looks like you staying because I asked, leaving when I need solitude, and not treating my decisions—including bad ones—as problems you’re obligated to solve. If you’re here to prevent suicide as a mission parameter, that’s management. If you’re here because you want to spend time with me and suicide prevention is a consequence of that presence, that’s different. So which is it?”

Jon rubs his chin, thoughtful.

“I see what you mean. First of all, I must clarify, in case you haven’t noticed, that I’m not remotely as intelligent as you are. I can time-travel and all, but it’s not like that made me a genius. So you’ll have to be a little patient with my thought processes. Alright, when I figure out a plan about anything involving your life, I’ll lay it out, ask whether it feels right for you. And if at any moment you want me to scram, just say so and I’ll disappear. But if suddenly you decide that you want to kill yourself despite your brother Bobby waking up eventually, despite having your own mansion and financial help… I mean, I’ll have to restrain you and prevent you from killing yourself just on principle. Do you think that would be unreasonable?”

That’s honest enough to be useful. But it also means if I accept this arrangement, I’m accepting a jailer who believes he’s protecting me from myself. Maybe that’s reasonable—maybe suicide prevention is the one non-negotiable boundary that doesn’t constitute management—but I need to think about whether I can live inside that constraint for four months without feeling like I’m back in institutional custody with better amenities.

“Which means this isn’t companionship without conditions—it’s rescue with override authority. That’s management, Jon. You’re offering me a mansion and infinite resources and Bobby’s extraction, but the price is accepting that my autonomy is conditional and you retain veto power if I decide the universe is still structured for destruction and suicide becomes necessary again despite the intervention. So let’s be clear—are you offering companionship where I set the terms, or are you offering supervised relief where you intervene if my decisions conflict with your mission to keep me alive? Because those are different relationships and I need to know which one I’m actually accepting before I let you restructure my entire material reality around your apparatus.”

Jon shakes his head slightly.

“I’m sorry, Alicia, but I don’t accept your dichotomy. If I get to know you to the extent that I like you as a person, as a friend even… if I happened to find out you intend to kill yourself, would me trying to stop you be ‘supervision,’ or just the pure natural reaction to someone you care about trying to remove themselves, even though their decision could have been made under a temporary mental disruption?”

The careful negotiation drops away from Jon’s expression.

“I guess I’ll make it clear,” he adds. “I intend to keep you alive under all circumstances, Alicia. And I wish to offer you a better life than your meager, depressing current one, until your brother Bobby joins your side. When your brain makes up its mind and convinces you that extinction is the best course of action… well, it was wrong this time, wasn’t it? Your brother eventually woke up, and your death was a horrible tragedy. My job is to prevent that from happening.”

Maybe that’s what I need. Someone who won’t leave when my brain tells me to die. Someone who’ll hold the line when I can’t argue with myself anymore. The weight behind my ribs shifts—not gone, but different.

The silence stretches between us. This is rescue with veto authority, companionship is optional, and he’s not negotiating the suicide-prevention parameter.

Jon watches my face, then sighs.

“This has been a lot to take in, hasn’t it?” His voice softens. “It’s nearly midnight. You must be exhausted, and you have a lot to think about. Would you prefer for me to leave for tonight so you can sleep? I can come by tomorrow morning, bring you breakfast.”

I don’t answer. Just stand there, letting the silence sit.

He nods, then smiles at me.

“Alright, I’ll let you be. Good night, Alicia. I hope that before you fall asleep you remember that soon enough you’ll be in your own place, a house big enough that nobody will bother you, and with Bobby recovering in one of the rooms. I hope that when you wake up, things feel lighter for you. See you in the morning.”

Jon vanishes from the room. Disappears instantly—one moment standing there, the next just gone. The air where he stood settles back into stillness.

I’m alone again. The fluorescent hum fills the silence.

I am exhausted. Two days of holding the line against institutional concern, writing the letter, the Kid’s intermittent visits, Jon’s arrival with the photo and timeline and sovereignty interrogation—it’s been sustained cognitive load and I can feel my thinking starting to fray at the edges.

Better to lie down, let the mattress take the weight, see if sleep arrives or if my mind just continues processing the question: do I believe the photo is real. Do I believe Bobby woke up. Do I believe the universe allowed one structural exception to its design principle that everything created gets destroyed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.