Hunger and sex tingling at the base of my skull, I set the excerpt beside me on the eroded, lichen-stained stone blocks. The roar of a passing car from the abutting road faded, allowing the chorus of birds to swell in a contest of chirps and warbles. Through the gap between two dilapidated walls, the nearest apartment building emerged, its bricks a medley of rust red, chocolate brown, and burnt orange. The windows reflected the sun’s warm glow. Over a balcony’s parapet, a woman’s bust, wearing a blue robe, watered a row of potted plants, her wet, dark hair gleaming as if lacquered. Overhead, puffy clouds stretched across an azure canvas, drifting slowly by like towering snowdrifts. A wash of sunlight bathed the world, but the undersides of some clouds had darkened from a ghostly white to a charcoal gray.

“Gorgeous, isn’t it?” Elena said in a measured tone. “Gigantic cotton balls in creative and unique shapes, suspended who knows how many kilometers above our heads. A painting ready to be rendered. Our lives look so tiny and lackluster compared to nature. Have we really improved much from the days when we lay in a field and stared at the sky? And at night? We’ve never seen those stars our ancestors took for granted. We never learned the stories they read in those constellations. Besides, imagine the amount of UFOs they must’ve witnessed zipping around up there, without comprehending what the fuck they were looking at.”

“As if we understand. By the way, iron age life expectancy hovered around twenty years. Half of children didn’t make it to puberty. Trepanning was used as a cure for migraines. People died from a mild infection, or from shitting. There were no books, no movies, no computers, and you were lucky if you had a wooden horse, and a piece of hard bread to gnaw at.”

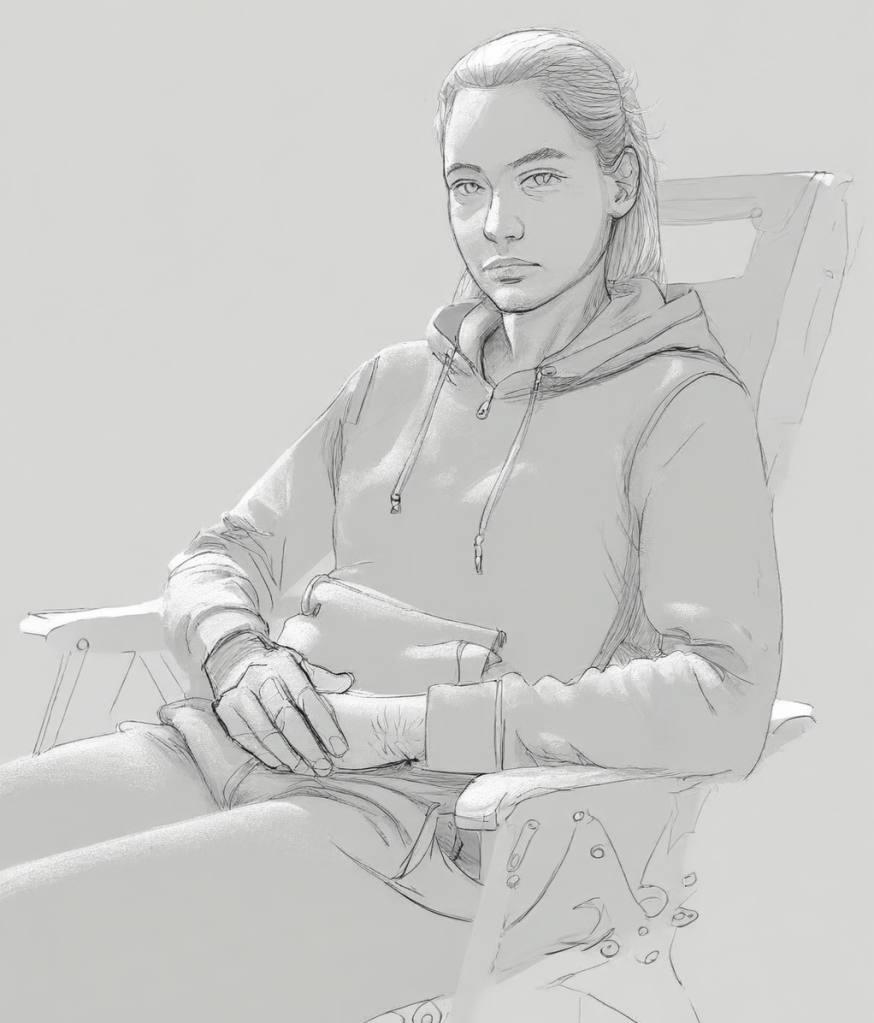

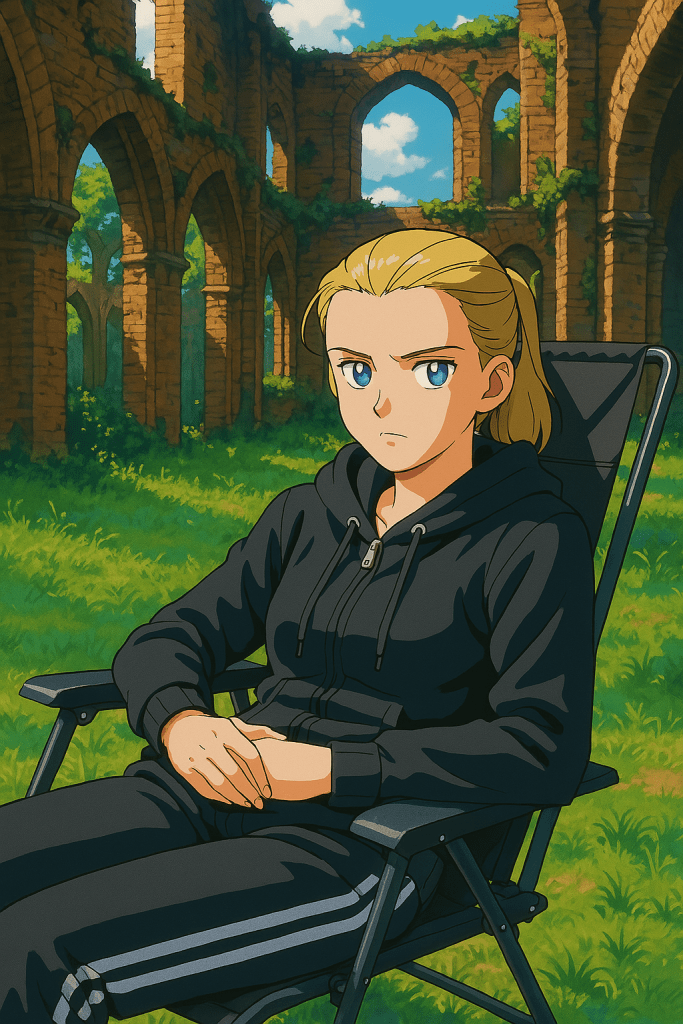

Elena had crossed her alabaster ankles, smooth skin revealed beneath the hems of her black joggers, that had slipped up the shins as she reclined in the lawn chair. The pack of cookies rested on her lap. Her pallid face bloomed in the sunlight like an unfurled moonflower. I beheld a quasi-mythical creature, rare as the sight of a narwhal’s tooth cleaving the surface of the Arctic Ocean.

“Well, aren’t you full of facts? You’ll explode like a piñata. But you’re right. Most people’s lives throughout the ages were wasted in perpetual crises. And here we are, wasting our lives in the midst of supposed plenty, and still suffering.” She shifted in the chair, the plastic strips creaking as she brushed cookie crumbs off her hoodie. Her pale blues searched my face anxiously. “Come on, blurt it out. You know I’m waiting for the verdict.”

“I’m still coming to my senses. Let’s recap: a man and a woman locked in a relationship without the slightest interference. He refuses to leave that secluded clearing because the outside world is… meaningless and hostile. Worse than the risk of starvation. Their relationship is as co-dependent as that of a parasite and host, and maybe I should be disturbed by the cannibalism, but… reverting to a primal state, losing yourself in intimacy with the sole existence that matters in the universe, feels holy to me.”

Elena’s gaze slid down to her fingers clutching the pack of chocolate cookies. The inner corners of her blonde eyebrows slanted upwards. As if she had won a struggle with herself, her pale blues snapped up and locked with my eyes. Her mouth curved into an impish smile.

“What deeper connection could exist, what greater intimacy and trust, than allowing your beloved to tear out and devour pieces of your body?”

“Yeah. Remind me to never stick my dick in your mouth.”

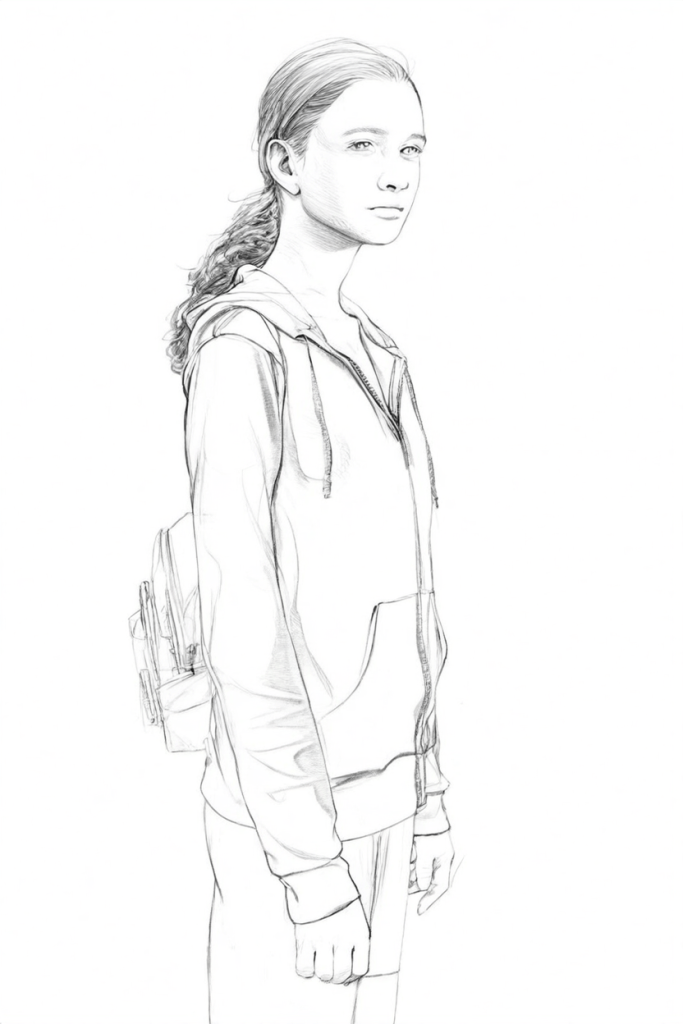

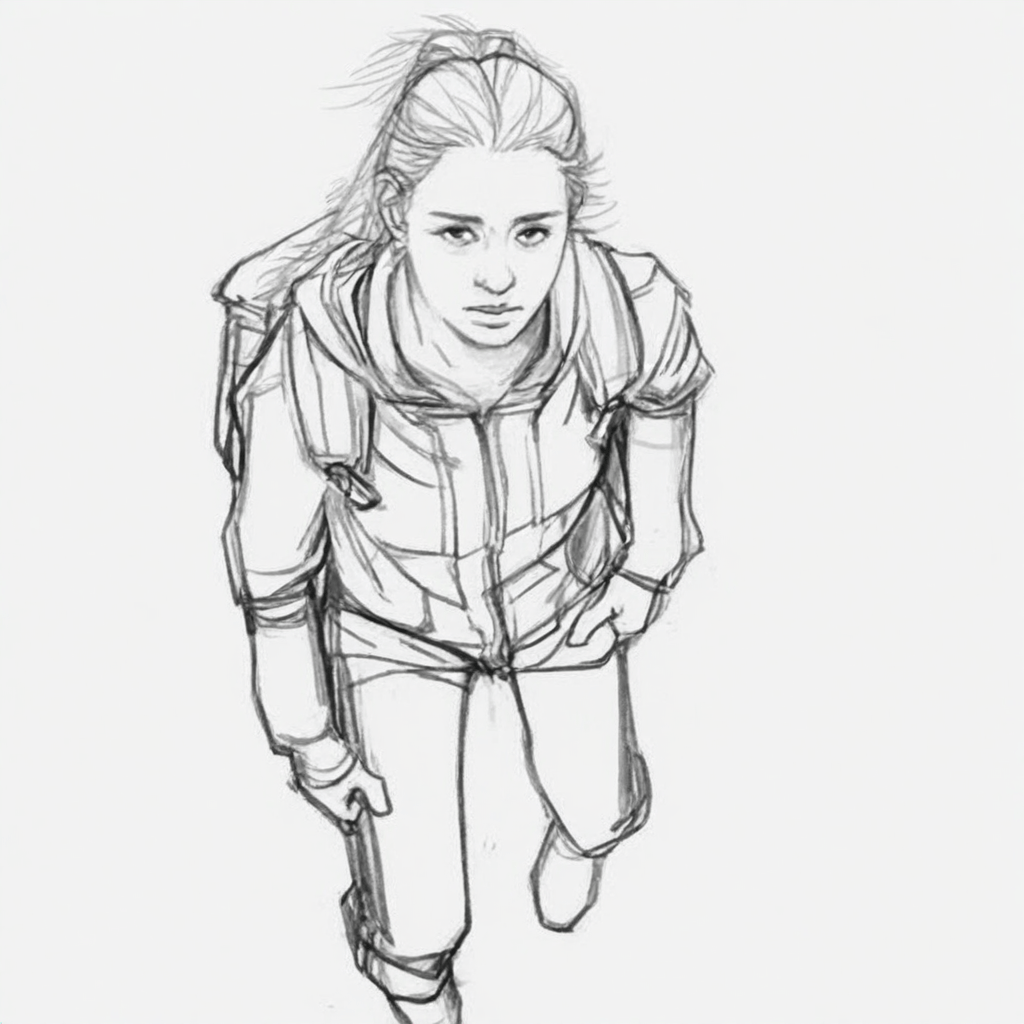

After an explosive “pfft,” Elena erupted into a hearty laugh—a wild blend of a crow’s cawing and a hyena’s yapping—that rattled her shoulders. Doubled over, she let her head slump between her arms while her almond-blonde hair shimmered like spun gold in the sunlight. She raised her head, revealing her cheeks flushed pink. I couldn’t help but grin. As her laughter dwindled into a chuckle, she leaned to the side and plunged a hand into her open backpack. With a crisp crinkle of plastic, Elena fished out the bag of salted peanuts and lobbed it at me. I caught it by pressing the bag against my chest.

“Is this your way of telling me to stuff my own mouth?”

“You need to eat. You were starving yourself while you read about a guy feasting on his girl. At least nibble on some nuts, you big, bearded weirdo.”

I shrugged, then tore the bag open, unleashing the scent of salty, roasted peanuts. I poured a handful and shoved them into my mouth. My taste buds tingled with salt as I crunched down the nuts. Elena picked up a cookie from the pack on her lap and bit it in half, her head tilted back slightly, exposing her throat as she studied me.

“Allow me to ruin the moment,” I said, “by bringing up that being eaten alive must be one of the most horrifying ways to die. I read about a teenager, I think in Russia, who texted her mother as a family of bears were gorging themselves on her flesh, and I wish I could scrub that shit out of my brain.”

Elena swallowed. A shadow passed over her face despite the sunlight streaming down.

“I read that too. Funny how we cling to such horrific stories. Like picking at scabs. We can’t wait for the apocalypse, huh? Maybe we’ll get to chew on each other. Yeah, I doubt I meant the cannibalism literally. It’s more of… what would you call it? A metaphor?”

“Or a symbol.”

“Well, who the fuck cares about the labels academicians slap on things. What matters is the experience. I didn’t come up with that particular element of the story, though. My monster presented it to me, as in, ‘Oh, you should have the narrator feed from that lagoon woman for nourishment,’ and I went along. Felt right.”

Elena wedged the rest of the cookie into her mouth. I tossed another handful of peanuts into mine.

“At a middle level of meaning,” Elena continued, her voice distorted by cookie chunks, “I suppose it relates to how I imagine complete intimacy: letting someone peel away all the layers of yourself, exposing what you try to conceal, the parts that disgust and shame you, and learning they can accept those too. Most people can’t handle seeing what’s beneath someone else’s skin, let alone consuming it. They want sanitized relationships that don’t make them question their own humanity. No dirt, no grime, no stink. But in that clearing… that’s what love might look like if we stripped away the social conditioning that turns us into dishonest creatures, instead of the wild animals we really are. Neither of them is trying to change the other. The narrator accepts that she needs to submerge in stagnant water for dozens of minutes at a time, and return to his embrace soaking wet and covered in pond scum. And she accepted him from the moment he stepped into that clearing. Two people finding comfort in their shared fucked-up-ness. Cannibalism as communion. Total surrender. She’d rather be devoured piece by piece than let him leave. And he’d rather starve than return to a world that doesn’t contain her.”

Elena’s features twisted in tension—brows knotted and lips pursed as if battling an internal pressure. She had hunched slightly, shoulders drawn inward. Her expression melted, and she pressed a hand against her stomach.

“Almost burped. I don’t know why I eat these cookies. They always make me feel bloated.”

“Is that what you want?”

“Is what what I want?”

“To live in isolation with someone who loves you.”

She whipped her head to stare at me with wide, naked eyes, her lips parted. I had never witnessed her speechless, as if she had short-circuited. When the power flickered back to those pale blues, Elena averted her gaze and fiddled with the zipper of her hoodie.

“Straight to the point, huh? Bold motherfucker.”

“And I expect a bold answer.”

Elena reached down for the carton of orange juice, unscrewed the cap, and guzzled, her throat contracting as she swallowed. After setting the carton on the ground, she fixated on the eroded stones beside me rather than meeting my eyes. Her upper lip glistened from moisture.

“I guess you expect me to say that I want to be with someone who sees the real me, who shows me how it feels to be loved and accepted. Who makes me feel less alone in the world. Sadly, I was tempted to pretend I haven’t fantasized about that, but the ghosts in my daydreams aren’t flesh and blood, which means I can spend eternity in their company.”

“And shape them to your liking.”

“Sure. They can’t leave. They can’t disappoint me.”

“Or hurt you.”

Elena’s pale blues flicked up to my face, then away, as her shoulders stiffened.

“Listen, Jon. When real humans are involved, my body, my brain, they react in predictable ways. As if those people and I belonged to separate species. A relationship that works in my imagination would turn unbearable in person. I’d grow to hate their voice, their breath, their smell, the sound of them breathing. To the extent that I’d want to strangle them. I’d unconsciously push them away until they gave up on me. And I’m not sure I’m capable of loving someone. I can’t even stand myself.” Elena exhaled, then rubbed her eyelids as if to hide in that darkness. “To survive, we tell ourselves stories about how we’d love to spend our limited lives, but it all boils down to how you’re wired, how your neurological makeup processes reality. And to me, it feels like a nonsensical succession of bristly, abrasive stimuli. Add in the horror of inhabiting a mortal body. Your skin itches, your guts twist, your head aches. In constant conflict with the sack of flesh and bones you’re forced to nourish and maintain. Pissing and shitting and horking snot and vomiting, bleeding out every month if you’ve got a cunt, then menopause and wrinkles and everything sagging to shit. I’d rather free my consciousness from this monkey suit and install it in a robotic body that would allow me to modulate sensory input, or even turn it off. Instead, I’m trapped in a puppet of decaying meat colonized by trillions of microbes. And it will fail on you one day, you know. Despite everything you’ve sacrificed, it will betray you. At the very least, your neurons will fry and you’ll lose track of where and who you are. And in the end, the Earth, the sun, the universe itself will succumb to entropy, so none of it matters. What a nightmare. If my brain hadn’t been shaped so strangely, maybe I wouldn’t feel trapped in this miserable hellhole of a world. All I see in the mirror is a broken, twisted, parasitic organism doomed to an eternity of solitude. Might be the least she deserves for being defective and bringing misery to others.”

“You have a right to be happy, Elena. Try to extract as much joy from this nonsense as you can.”

Elena dropped the cookie pack into her backpack before curling into herself, hugging her knees to her chest. The parallel white stripes rippled along the creased fabric of her joggers, evoking a flag fluttering in the breeze. Her tired eyes, stark against the dark shadows beneath them, locked onto me with an unblinking intensity.

“Let me get to the point, Johnny. That story was inspired by something stronger than love. Something that has kept me alive despite my longing for death.”

“Stronger than love, huh?”

“Oh, yes. Like a black hole to a star. A force of nature that warps the fabric of reality. A gravitational pull that can’t be resisted or escaped, that bends the light of the stars and the flow of time. Want to hear the details?”

“I want to hear everything about you. Lay it on me.”

“What a gracious gentleman. Well, let me bring you back to the days when I worked as bookstore clerk, or whatever the fuck they call that. In Gros. That daily sacrifice to the gods of the rat race for the sole purpose of amassing money, a purpose to which we’re born enslaved. Anyway, I include the hour-long commute each way in crowded buses and trains. How many times did some motherfucker rip a fart, forcing everyone in the vicinity to inhale his putrid gases? A wafting shit mist that clung to the inside of your nostrils.” Elena rubbed her face with her palms. “Let’s move on. Whenever I stocked the shelves, or dealt with my coworkers and customers, or just sat in the back room with my face in my hands, I yearned to hide from this world that grinds us into dust, that demands we participate in its meaningless rituals until we’re hollowed out. I longed to escape to a secluded place where I could be my true self, where no one would find me and drag me back. Once you know that such a sanctuary exists, even in your imagination, the tiny, sterile reality you’ve been confined to from birth asphyxiates you. I’ve been there, Jon. In that secluded clearing. Not literally eating people, obviously—although my intrusive thoughts love to provide detailed instructions from time to time. Inside that sanctuary, the mere thought of returning to the cold machinery of society made my blood curdle.” She rested her chin on her knees, her pale blues vacant as if gazing into another dimension. “I’ll open up about something hard for me to articulate. I’ve never before attempted to put it into words. But that’s the point of these meetings, right?” Elena’s fingers dug into her kneecaps. She closed her eyes, her features strained. “In that sanctuary, I was rarely alone. You could say I retreated to the clearing to meet someone. A presence that had become more real than my own body. Whose words mattered more than food, or air, or sunlight. Whose existence justified mine. Whose essence, freely shared, I consumed, trying to transform myself into someone deserving of her gifts. She was the reason I kept going, the reason I woke up every morning. Because I knew she’d be there.”

Elena’s breath hitched. We had stepped past her writing onto the jagged brink of an unhealed wound. Her furrowed brows and the tension around her mouth betrayed her struggle to remain in control.

“You were in love, then,” I said. “Who’s the lucky woman?”

Her chest heaved as she inhaled deeply. After opening her eyes, she locked a piercing gaze on me as if punishing herself. Those pale blues, haunted by a beast’s sorrow, gleamed with a liquid sheen that pooled at the waterline. A glistening crystal bead spilled over and clung to the lashes.

“I… I can’t, Jon,” she said in a ragged voice. “Now, I cannot.”

“No pressure. You don’t owe me anything, Elena. Least of all your pain.”

“I would never call it love. You have to understand. She made my existence bearable. I yearned to take her inside me so utterly that the boundaries of our selves would dissolve, and she would flow through my veins and seep into my bones. I knew that returning daily to her presence would… But what was the alternative? Streetlights and vending machines? The rest of the world is noise. I’d rather be consumed by something meaningful. Even if it destroys me. No, especially if it does.”

From the shadows under Elena’s brows, her eyes still reflected the sunlight as she averted her gaze. Her lashes swallowed the solitary tear.

“I hate slapping labels on things. Words are crude trade-offs in which to cram whole universes of meaning. In some cases, people cage those meanings into words precisely to lock them away. But human beings can’t pour the contents of their minds into other skulls, hence the insufficient, clumsy tool of language. Let me use the dreaded O-word to sum it up.”

“Which one? Oblivion? Onanism?”

Elena’s eyes snapped back to me. Her lips stretched into a wry smile.

“Obsession, you dickhead. It lacks the dignity and respectability of love, but it’s got teeth. And claws. Sharp ones that sink into your brain and won’t let go. When you’re obsessed, you don’t need to be loved in return. You’re content to feed off scraps. Back to the lagoon woman, I needed her identity to stay a mystery. I thought of her as a black hole, an unknowable singularity. Anyone approaching her would get sucked in and distorted beyond recognition. A mind warping around a mind warping around a mind.”

After rubbing her hands on her joggers, Elena lowered her feet to the ground and leaned forward to seize the carton of Don Simón. She unscrewed the cap, then drained the container dry as it dented in her grip. She screwed the cap back on and stuffed the empty carton into her backpack.

“You know, years ago, a therapist told me I couldn’t possibly feel soothed by my obsessions. Their bible—the DSM—didn’t allow it, at least as it came to the OCD label she intended to staple onto my poor, troubled head. I wish I had told her to fuck off. Don’t get me wrong… My obsessions have contaminated me. But worse, I feared that my fondling and drooling might taint their purity.” She sighed and shook her head. “There’s no way to sugarcoat this, Johnny: I’m the most obsessive person I’ve ever known. Outside of those you only find out about because…” Her voice grew brittle, on the brink of cracking. “Because they walk up to their idol and stab them in the heart.”

Author’s note: today’s song is “Hotel California” by Eagles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.