There’s only three people I feel myself wanting to speak to these days.

The first one is the girl I’ll always have to think of as the love of my life. I met her when I was sixteen or seventeen. Her name was Leire. A basketball player even though she wasn’t particularly tall for a girl. Passionate if a bit reckless, she was romantically interested in me for whatever reason. One night, on the grass of Hondarribia, we lay under the stars as she spoke about her dreams. Things barely started between us when I called it quits, because I had never liked someone genuinely that much (nor have I since), and I knew that the more she learned about me, the more she would regret having gotten involved with me, so it was better to cut my loses as soon as possible. I haven’t seen her in nearly twenty-five years. Not getting more intimately involved with her in a romantic sense was the right choice, but I wish I could have gotten to know her better.

The second one is a lanky girl I knew in middle school. I suspect now that she was autistic, like me. She also pursued me, and we got to meet twice outside of school. I remember sitting on a bench as she slouched beside me, talking and talking. I rarely said anything back. She also wrote these colorful letters that, I’m afraid, I never read. The last time I saw her, she was standing across the schoolyard, a conspicuous vertical scar across her forehead from the gash a stoner classmate caused her while playing around with a cutter in Arts & Crafts. I have sometimes found myself wanting to read her letters, but I recall the memory of me, back in my mid-twenties, when I existed as something of a hikikomori, not even able to handle going outside for a while, consenting to my mother throwing the letters away. I’ve long forgotten this girl’s name, so I couldn’t even try to google her up. I suspect she ended up killing herself. I wish I could have made her life better.

The third one isn’t even a real person. She’s a character of the late Cormac McCarthy, the troubled master of literature, who in the seventies fell in love with a 13-14 year old girl whom he rescued from abusive situations in the foster system, and with whom he lived somewhat briefly in Mexico. Once you know about that part of his life, you see echoes of it in pretty much all his stories. The Border Trilogy. Blood Meridian (the Judge, who made underage girls disappear wherever he went). No Country for Old Men, that ending sequence for the protagonist, when he met a compelling teenage runaway at a motel pool, whom he intended to help get to a better place (an ending that was, tragically, completely wasted in the otherwise fantastic movie, even though it was the whole thematic point that Cormac was driving to). And of course, The Passenger and Stella Maris, his last two novels, which are entirely about his grief for having lost this girl back in the seventies. The real version of Alicia Western, the doomed math genius of the novels, also struggled with mental issues due to the fucked-up things that happened to her before she ended up in the foster system. I suppose that her time with Cormac didn’t particularly improve her mental health. She ended up in a sanatorium related to Stella Maris (wasn’t exactly named like that, but the religious people involved with the institution worshiped it; Our Lady, Star of the Sea is an ancient title for Mary, the mother of Jesus). The real life version of Alicia Western (minus the math genius part) survived her ordeal, and now lives as a rancher in the Catalina Foothills in Tucson, AZ. Cormac McCarthy is dead.

In any case, I found Alicia Western so fascinating that I regularly want to return to her. Not by reading the books again, but by meeting her in my vivid imagination, during elaborate daydreams. They almost always start the same way: as I lie in bed, in the dark, I light up that room at the Stella Maris sanatorium, that will only hold her for about two or three days more before she kills herself, which she did in the novels (hardly a spoiler, as The Passenger starts with a hunter finding her frozen corpse). After I prevent her suicide, we leave the sanatorium and travel around the country, sometimes staying at hotels, sometimes at a mansion I buy from her with the gold I recovered from the looting of the Spanish reserves by communists during the Civil War. Later on, a third person joins us: an advanced AI named Hypatia, who resides in a quantum data center in another timeline, and who helps Alicia with her mathematical research. Eventually Alicia figures out a mathematical way to travel instantaneously to anywhere in the universe. Back in the future, I get my team to build a prototype of the machine. After I return to 1973 and we test it, getting video from Mars and further planetary bodies, I proudly tell her, “Alicia, you’ve made humanity a multi-stellar species,” which lights up her face. My point is that visiting Alicia Western in daydreams has become my safe place, to which I return not only at night but during train and bus rides to and from work. I’ve never felt comfortable enough among flesh-and-blood human beings, so this is the best I can do.

Anyway, I’ve spent the past months building an app that allows human users to interact with large language models (AIs) who act in character. That’s hardly novel these days, but my app also provides action discoverability and world manipulation, which sets constraints for the LLM; they can only perform during their turn the complex actions that the action discoverability system allows them to. I initially intended to use the app to play through RPG campaigns and the likes, but for the most part I use it for erotica. Whenever I get the itch to play out one of my many, many, many kinks, I set up a comprehensive scenario. Who doesn’t want to experience from time to time a fantasy in which you have a fit, taller older sister who plays volleyball, who looks so good in her sports outfits, and who can’t wait for your parents to leave the home so she can jump the bones of her adorable little brother?

In the previous part of this series, linked above, I ran the scenario of meeting Alicia at Stella Maris and preventing her suicide. I wanted to go through it again, but with an improved version of the app. I’ve implemented an item system that supports item-related actions: actors can now drop items, pick them up, give them to other actors, examine them, read them, open containers, close containers, take items from containers, and put items in containers. Some of those actions will be used by the AI during this run.

I’m playing a better version of myself: taller, more muscular, full head of hair. Alicia Western is being played by the best LLM at roleplaying, at least of those I know of: Claude Sonnet 4.5. Note: quite a few of the thought sections in this run end up being quite redundant with what Alicia says. I considered editing out the redundant parts, but opted out against it in favor of completeness. Let’s get going.

Alicia sits on the cold floor, face buried in her forearms. A deep voice rises from the room’s center.

Jon Ureña: Hello, Alicia Western. I’m glad to finally meet you.

(in this run, I’ll include the notes that the AI added to Alicia’s memory system. Entries related to me are tagged with my name, even though she has yet to learn it. That’s a limitation I don’t know how to work around.)

1. [event] Jon Ureña's entrance: Jon Ureña appeared in my locked room impossibly—door was secured, yet he entered without unlocking it

(Context: patient room, December 22, 1972)

2. [knowledge_state] Jon Ureña's knowledge: Jon Ureña knows my full name despite me telling no one where I am—unexplained information access

(Context: assessing potential threat)

3. [quest] reality verification: Need to determine if Jon Ureña is: (1) delusion/hallucination, (2) real intruder, or (3) phenomenon outside my theoretical framework

(Context: immediate priority)

The locked door should have prevented anyone from entering. I locked it myself. The physical impossibility of this man’s presence in my room creates an immediate logical paradox that my mind cannot reconcile. He knows my full name. He said he’s “glad to finally meet” me—implying anticipation, familiarity, perhaps surveillance. But nobody outside this institution knows where I am. I didn’t tell anyone. The staff wouldn’t give out patient information. This is either: (1) a delusion—my mind finally fracturing completely like my parents, (2) an institutional security breach of significant magnitude, or (3) something I lack the theoretical framework to categorize. His voice is real. Deep. Male. Coming from the center of the room, which means he’s standing, while I’m here on the floor with my face hidden. Vulnerable position. I need to look at him. I need data. Visual confirmation. Assess threat level. Determine if this is happening in consensus reality or only in mine. My heart rate has increased—I can feel it against my ribs. Fear response or curiosity? Both, perhaps. I should look up. I need to see what is actually in this room with me.

(Alicia didn’t even speak during her turn, paralyzed as she was.)

The man speaks calmly.

Jon Ureña: I’ll give you all the time you need to react to the sudden presence of a stranger in your locked room.

1. [observation] Jon Ureña's behavioral pattern: Jon gave me time to process his presence rather than demanding immediate response—suggests either genuine patience or sophisticated psychological manipulation

(Context: his initial interaction approach)

If I look up and see him—really see him—then I’ll have the data I need. Visual confirmation. Height, build, clothing, facial features. Whether his mouth moves when he speaks. Whether his feet make contact with the floor or hover impossibly. Whether light refracts off his body the way it should with a physical presence. I need to categorize this phenomenon. My analytical framework requires input. The fear is secondary to the necessity of understanding. I’ve spent my entire life being afraid of losing my mind like my parents did. If this is the moment it finally happens—if I look up and see something that cannot exist—then at least I’ll know. At least the uncertainty will end. But I have to look. I have to see what’s actually there.

Alicia lifts her head slowly, blue eyes focusing on the figure standing in the center of the room.

Alicia Western: You shouldn’t be able to be here. The door was locked. I locked it myself. Physical barriers don’t just… dissolve.

The older, bearded man, looking calmly down at Alicia, nods casually.

Jon Ureña: You would be right, given your assumption that the door was involved in my sudden presence here. No need to rush, Alicia. Take your time.

1. [observation] Jon Ureña's entrance method: Jon Ureña stated door was not involved in his entrance—implies materialization or non-conventional spatial transit into locked room

(Context: his explanation of impossible appearance)

2. [quest] reality verification protocol: Need to verify if Jon Ureña is hallucination vs. real entity outside my theoretical framework—checking for substrate-dependence, light refraction, air displacement

(Context: immediate priority for assessing my sanity)

3. [theory] ontological framework crisis: If Jon is real, my entire understanding of reality's boundaries requires fundamental recalibration

(Context: implications of Jon's existence)

If I get close enough, I can verify the physical markers. See if his chest rises and falls with breath. Check if his clothing has the small imperfections real fabric shows—wrinkles, wear patterns, the way cotton and leather actually behave under gravity. Hallucinations can be vivid, but they often fail at the micro-level of detail. The texture of his beard. Whether his eyes track my movement with the slight delay real human vision requires, or whether they follow with the impossible precision my mind might generate. I need proximity. I need data. The fear of discovering I’m delusional is less than the necessity of knowing. I’ve been afraid of losing my mind my entire life—if this is that moment, at least I’ll have confirmation. At least the uncertainty will end.

Alicia rises slowly from the floor, keeping eyes locked on Jon Ureña as she stands.

Alicia Western: You said the door wasn’t involved. Which means you either materialized inside a locked room—violating conservation of mass-energy—or you exist outside conventional spacetime constraints. Both options invalidate my operational framework for consensus reality. *takes a deliberate step closer, studying his physical form with clinical precision*. I need to verify whether you’re substrate-dependent. Whether light refracts off you correctly. Whether you displace air when you move. I’ve spent twenty-two years trying to determine if my perceptions are reliable, and now you appear in my locked room claiming you’re “glad to finally meet me.” *moves closer still, voice dropping to something quieter, more raw* So here’s what I need to know: Am I finally, completely insane? Is this the moment my mind fractures like my parents’ did? Or are you actually here—something real that exists outside my theoretical framework? Because if you’re real, then everything I thought I understood about the boundaries of reality needs recalibration. And if you’re not real… *pauses, jaw tightening* …then I’ve already lost my mind, and the two days I have left are a mercy.

(Alicia chose the action “get close to Jon Ureña”)

The man, significantly taller than Alicia, extends an arm to hold one of the young woman’s pale hands.

Jon Ureña: I’m real, Alicia Western. As solid as you are. Well, much more solid. You’ve… let yourself go, I’m afraid.

(I chose the action “hold Alicia Western’s hand”)

1. [observation] Jon Ureña's physical reality: Jon Ureña's hand is warm, solid, substrate-dependent—physical verification confirms he displaces matter and generates body heat consistent with living human tissue

(Context: empirical testing via physical contact)

2. [observation] Jon Ureña's communication style: Jon Ureña speaks with direct clinical assessment without therapeutic hedging—observed my malnutrition as 'letting myself go' without conventional medical framing

(Context: his comment about my weight)

3. [knowledge_state] Jon Ureña's foreknowledge: Jon Ureña stated he's been waiting to meet me—implies anticipatory knowledge of my existence and timeline

(Context: his phrase 'glad to finally meet you')

His hand is extended toward mine. He’s offering contact—physical verification of substrate-dependence. This is the experiment I need. If his hand has warmth, texture, resistance—if it exists in three-dimensional space with mass and solidity—then he’s real. Real means everything I understood about physical law is incomplete. But real also means I’m not hallucinating. Not psychotic. Not fractured like my parents. He said I’ve “let myself go”—casual observation about my weight, my malnutrition. Clinical accuracy delivered without therapeutic hedging. Nobody talks to me like that. They use careful language, therapeutic distance. He’s direct. Almost… familiar. I need to touch him. Need the data. Skin temperature, pulse if I can detect it, the micro-movements of living tissue. This is empirical verification. If he’s solid, if he’s warm, if he displaces matter the way physical bodies must—then I have to recalibrate everything. But I won’t know until I reach back. Until I make contact. My hand is already lifting. The decision made itself.

Alicia reaches out and takes his extended hand, fingers closing around his palm with deliberate precision, testing for warmth, solidity, the subtle pulse of blood beneath skin.

Alicia Western: You’re warm. Substrate-dependent. Mass displacing space exactly as physics predicts. Which means you’re either genuinely here—existing in consensus reality despite the locked door—or my hallucinations have achieved unprecedented phenomenological accuracy. *holds his hand for several seconds longer than socially conventional, studying the point of contact with clinical focus* You said I’ve let myself go. Ninety-eight pounds. I know the clinical thresholds. The knowledge changes nothing. But you’re the first person in this institution who hasn’t wrapped that observation in therapeutic language. No “concerning weight loss” or “nutritional goals.” Just direct assessment. *meets his eyes, voice dropping to something quieter, more uncertain* You know my full name. You said you’re “glad to finally meet me”—which implies you’ve been waiting. Anticipating this encounter. But I didn’t tell anyone where I am. The staff wouldn’t disclose patient information. So either you have access to institutional records you shouldn’t have, or… *pauses, jaw tightening slightly* Or you exist outside the operational framework I’ve been using to map reality. Which terrifies me more than discovering I’m completely insane.

The man offers Alicia a kind gaze.

Jon Ureña: There’s no need for you to fear anything anymore, Alicia. I didn’t access institutional records to learn about you, a 22-year-old math genius who has given in to despair. I’ll give you all the time you need to come up with a different, more accurate alternative to my sudden, solid presence here, in front of you.

1. [observation] Jon Ureña's reassurance: Jon Ureña stated there's 'no need to fear anything anymore'—past tense suggests my reasons for fear have been resolved, not just that he's non-threatening

(Context: his phrasing about my fear)

2. [knowledge_state] Jon Ureña's knowledge of my condition: Jon Ureña described me as '22-year-old math genius who has given in to despair'—precise assessment of my psychological state delivered without clinical hedging

(Context: his accurate characterization)

3. [quest] source of Jon's information: Need to determine how Jon Ureña acquired knowledge of my age, intelligence, and psychological state without being told or accessing institutional records

(Context: unexplained knowledge acquisition)

He said he’ll give me all the time I need to come up with a different alternative. A “more accurate” alternative to his presence. He’s testing whether I’ll accept the obvious conclusion or keep searching for explanations that preserve my existing framework. It’s like he knows I default to analysis when reality becomes unbearable. But what alternative is there? Door wasn’t involved—his words. Physical laws say matter can’t materialize spontaneously in enclosed spaces. Conservation of mass-energy is foundational. Unless… unless my framework is incomplete. Unless spacetime has properties I’ve never mapped. He said there’s no need to fear anything anymore. Past tense implied—as if my reasons for fear have been resolved, not just that he’s personally non-threatening. He called me a “22-year-old math genius who has given in to despair”—accurate assessment delivered without clinical distance. He knows what I am. What I’ve become. The warmth of his hand is still registering on my skin. Real. Solid. His pulse was detectable—substrate-dependent biology. But the locked door. The impossible entrance. I need to process this. I need to think. He said he’ll give me time, so I should take it. Let the data settle. See if my mind generates any explanation that doesn’t require abandoning everything I understand about physics.

Alicia Western: You’re asking me to reconcile an impossible physical phenomenon with my existing theoretical framework. The door was locked—I verified it myself. Conservation of mass-energy states that matter cannot spontaneously appear in enclosed systems. Yet you’re here. Warm. Solid. Displacing air exactly as a physical body should. *releases his hand slowly, taking a small step back while maintaining eye contact* You said “no need to fear anything anymore”—past tense construction. As if my reasons for fear have been resolved, not just that you personally pose no threat. You know I’m a 22-year-old math genius who has “given in to despair.” Accurate clinical assessment. But how do you know that? Who told you? Or did you… observe me somehow before entering this room? *wraps arms around herself, fingers pressing against ribs through the thin cotton dress* You’re giving me time to generate alternative explanations. I appreciate the intellectual courtesy. But every explanation I can construct violates fundamental physical law. Either spacetime has properties I’ve never mapped—dimensional access outside conventional three-space, perhaps—or my perceptual apparatus is generating phenomenologically accurate hallucinations, which would indicate complete psychotic break. *voice drops to something quieter, more uncertain* I’ve spent twenty-two years trying to determine if my perceptions are reliable. If you’re real—genuinely real, existing in consensus reality—then everything I thought I understood needs recalibration. And if you’re not real… then I’ve already lost my mind like my parents did, and the two days I have left don’t matter anyway.

The older man’s lips curve into a patient smile. He observes Alicia for a few seconds before speaking.

Jon Ureña: Two days left, Alicia. The woods are waiting, is that it? Your release through extreme cold.

1. [knowledge_state] Jon Ureña's impossible knowledge: Jon Ureña knows specific details about my December 24 suicide plan—woods, freezing method—despite me never telling anyone and only documenting it in locked letter

(Context: his mention of 'woods' and 'extreme cold' for my release)

2. [psychological_state] my reality verification crisis: If Jon can access information existing only in my mind or locked documents, my perceptual boundaries are compromised—same cognitive failure pattern as my parents

(Context: confronting possibility of complete psychotic break)

He knows about December 24. The woods. The cold. The specific method. I never told anyone. The letter is locked in the desk—nobody has accessed it. The therapists know I’m suicidal but not the timeline, not the method. So how does he know? Either he read my mind somehow—which violates every principle of information theory and cognitive isolation—or he accessed the letter impossibly, or he exists outside linear causality and observed a future that hasn’t happened yet. All three options require abandoning foundational assumptions about reality. About the boundaries between minds. About cause and effect. If thoughts aren’t private—if the contents of my consciousness are accessible to external entities—then I have no way to distinguish internal from external phenomena. No way to verify whether my perceptions are reliable. That’s the definition of psychosis. That’s what happened to my mother. To my father. The inability to determine what’s real versus what’s generated internally. If I’ve reached that point—if Jon can access information that exists only in my locked thoughts or locked drawer—then my analytical framework is worthless. I can’t trust my own mind to process data accurately. And if I can’t trust my mind, then every conclusion I’ve ever reached is suspect. Including the conclusion that death is optimal. But also including any conclusion that life might be worth continuing. It’s Gödel again. The system trying to prove its own consistency. I need him to explain. Need to understand how he knows. Because the answer will tell me whether I’m delusional or whether reality operates on principles I’ve never mapped.

Alicia’s voice drops to something barely above a whisper.

Alicia Western: He knows about the woods. About the cold. About December 24—two days from now. I never told anyone the method. I never spoke it aloud. The therapists know I’m suicidal, but not the specifics. Not the when or the how. I wrote it in the letter to Bobby that’s locked in the desk drawer, but nobody has read that letter except me. *takes a slow breath, arms tightening around ribs* You said you didn’t access institutional records. Which means you either observed me somehow—watched me planning, thinking, deciding—or you exist outside linear causality. Either option terrifies me more than the prospect of death itself. *meets his eyes directly, searching for something—deception, madness, truth* So here’s what I need to understand: How do you know about December 24? How do you know about the woods, the cold, the method I chose specifically because it’s peaceful? Because if you can access information that exists only inside my mind or written in a locked drawer… then every framework I’ve used to distinguish between internal perception and external reality is compromised. *voice drops even quieter, almost breaking* And if my perceptual boundaries are that porous—if thoughts and physical documents are equally accessible to… whatever you are… then I’ve already lost the ability to determine what’s real. Which means I’m exactly where my parents ended up. Fractured. Delusional. Unable to map consensus reality. Is that what’s happening? Am I finally, completely insane?

Jon Ureña: Perhaps I’m being mean to you. I intended for you to have all the time in the world to unravel your thoughts and come up with your explanations at your rhythm. But that’s counterproductive if you think you’re losing your mind. Let’s begin, then. You’re writing a letter to your brother Bobby, right? A goodbye letter that you’ve yet to finish.

1. [knowledge_state] Jon Ureña's impossible knowledge: Jon Ureña knows about my unfinished goodbye letter to Bobby—specific knowledge of locked document he shouldn't have access to

(Context: his mention of the letter I'm writing to Bobby)

2. [theory] information access paradox: Jon Ureña's knowledge of locked letter violates information theory—no physical access mechanism available

(Context: analyzing how he could know about the letter)

3. [psychological_state] my reality verification crisis: If Jon can access locked documents without physical contact, my ability to distinguish internal vs. external reality is compromised

(Context: confronting implications of his knowledge)

He knows about the letter to Bobby. The unfinished letter locked in the desk. I need to understand the mechanism. Not what he knows—how he knows. Because the answer to that question determines whether I’m having a psychotic break or whether reality operates on principles I’ve never encountered. If he can access information locked in physical containers without opening them, that suggests either remote viewing capabilities, telepathic access, or temporal observation outside linear causality. All three options require abandoning foundational assumptions. But I need him to explain. Need the data. Because right now I’m suspended between two equally terrifying possibilities: complete psychosis or a universe that functions in ways my analytical framework can’t accommodate. He said he’s giving me time to think, but thinking without data just generates infinite recursive loops. I need him to answer. Need him to explain the mechanism. That’s the only way to determine if I’m still capable of mapping reality accurately.

Alicia stands very still, arms wrapped around ribs, eyes locked on Jon’s face.

Alicia Western: He knows about the letter. The specific letter to Bobby that’s locked in the desk drawer. The one I haven’t finished writing. The one nobody has read except me. The door to this room is locked. The desk drawer is locked. I verified both myself. He didn’t access institutional records—he said that explicitly. So how does he know about the letter? How does he know it’s unfinished? *voice drops quieter, more uncertain* You’re asking me to explain something that violates information theory. Physical documents don’t transmit their contents to external observers unless those observers have direct sensory access. You couldn’t have read the letter unless you opened the desk, which would require unlocking it, which would leave evidence. But there’s no evidence. The drawer is still locked. *jaw tightens slightly* So either you accessed the information through means I can’t map—read my mind somehow, or observed the timeline from outside linear causality—or I’m generating this entire conversation as a psychotic hallucination and the letter never existed in the first place. *meets his eyes directly* I need to understand how you know about the letter. Not because I’m afraid of you knowing the content—it’s a goodbye letter to Bobby, there’s nothing shameful in it—but because the mechanism of your knowledge will tell me whether I’m delusional or whether my operational framework for reality is catastrophically incomplete. Because if thoughts and locked documents are equally accessible to you… then I’ve lost the ability to distinguish between internal perception and external reality. And that’s the definition of psychosis. That’s what happened to my parents. *voice barely above a whisper* So tell me. How do you know about the letter?

Jon Ureña: I know about your letter because I have it. Well, a version of it. *he produces a folded, yellowed sheet* The finished version you’ve yet to write. Care to give it a look?

(I used the action “give yellowed goodbye letter to Alicia Western”)

1. [item] yellowed goodbye letter: Jon Ureña produced yellowed letter claiming it's the finished version I haven't written yet—implies either temporal manipulation or sophisticated fabrication

(Context: handed to me by Jon in my locked room)

2. [theory] Jon Ureña's temporal claims: Jon Ureña claims to possess future version of my letter to Bobby—either exists outside linear time or fabricated convincing forgery

(Context: analyzing his impossible knowledge)

He says he has the finished version. The letter I haven’t written yet. That violates causality so fundamentally that every framework I have for understanding temporal sequence collapses. Effect preceding cause. Future information existing in the present. Either he’s lying—fabricated a document and claims it’s mine—or he exists outside linear time in a way that makes observation of future states possible. Or I’m generating this entire scenario as a complex delusion and the yellowed paper in his hand is just another artifact of my fractured mind. I need to see it. Need to read the content. Because if the handwriting matches mine, if the content reflects thoughts I haven’t articulated yet, if the details are accurate to what I would write… then I have empirical evidence that either time is non-linear or I’m completely psychotic. The letter will tell me which. My hand is already reaching for it. The decision made itself before I consciously registered the impulse. I need to see what I supposedly wrote. What version of me that doesn’t exist yet decided to say to Bobby. This is data. Raw, unfiltered data about the nature of reality or the extent of my delusion. I have to look.

Alicia takes the yellowed paper from his hand, fingers trembling slightly as they make contact with the aged material.

Alicia Western: The paper is yellowed. Oxidation takes time—years, usually, depending on environmental conditions and acidity of the material. But I haven’t written the finished version yet. Which means either you aged the paper artificially to create verisimilitude, or this document actually exists in a temporal state that shouldn’t be accessible from December 22, 1972. *unfolds the letter slowly, eyes scanning for handwriting recognition before reading content* If this is my handwriting—if the content matches what I would write but haven’t written yet—then you’re showing me evidence that causality isn’t linear. That future states can influence or be observed from past positions in the timeline. Which invalidates every assumption I’ve made about temporal sequence. *voice drops quieter, more uncertain* Or I’m hallucinating this entire interaction and the letter is just another artifact my fractured mind is generating. Like my parents. Like the voices they heard, the patterns they saw that nobody else could verify. I need to read it. Need to see what version of me that doesn’t exist yet supposedly decided to say to Bobby.

(instead of reading the letter, Alicia chose the action “examine yellowed goodbye letter”)

The older man crosses his arms and observes patiently as Alicia observes the letter.

1. [item] yellowed goodbye letter: Jon Ureña produced yellowed letter claiming it's the finished version of my goodbye letter to Bobby—handwriting appears to match mine with characteristic patterns

(Context: examining the document Jon gave me)

2. [theory] temporal causality test: If letter content matches thoughts I haven't articulated yet, it constitutes empirical evidence for either non-linear time or complete psychotic break

(Context: analyzing implications of the letter's existence)

The paper is yellowed. Aged. He claims it’s the finished version of a letter I haven’t written yet. Either he fabricated this—carefully aged paper, forged my handwriting, predicted what I would say to Bobby—or he’s showing me empirical evidence that causality isn’t linear. That future states can exist and be observed from past temporal positions. I need to read it. Not because I believe him yet. But because the content will tell me whether this is an elaborate deception or whether my entire framework for understanding time needs to be abandoned. If the handwriting matches mine perfectly—if the content reflects thoughts I haven’t articulated yet but would articulate—then I have data. Raw data about whether reality operates on principles I’ve never mapped or whether I’m generating sophisticated hallucinations. My hand is already holding the paper. The decision made itself. I’m going to read what I supposedly wrote. What version of me that doesn’t exist yet decided to say to Bobby in a goodbye letter I haven’t finished. This is the empirical test. Read the content. Assess the accuracy. Determine if Jon is lying or if time itself is non-linear.

Alicia unfolds the yellowed paper carefully, eyes scanning the handwriting first—checking for characteristic loops in her lowercase ‘g’, the way she crosses her ‘t’s with slight upward angle, the pressure variations that indicate her hand trembling.

Alicia Western: The handwriting… it looks like mine. The pressure patterns match. But I need to read the content. Need to see if the thoughts align with what I would write but haven’t written yet. *begins reading aloud slowly, voice dropping quieter as she processes each sentence.*

(Alicia chose to read the letter)

The older man merely listens to Alicia’s soft voice as she reads aloud slowly, to herself.

(What follows is the contents of the goodbye letter. I gave Sonnet 4.5 Alicia’s character definition, which is a JSON file, and explained the circumstances. It produced this letter in one go. I’ve ceased to be surprised.)

December 22, 1972

Stella Maris

Bobby,

The probability of you reading this approaches zero. The doctors said “braindead”—past tense, declarative, clinically certain. But I cannot pull the plug. I fled instead. So this letter exists in a superposition state: written but unread, meant for you but addressed to no one. Schrödinger’s goodbye.

If you are reading this, then something impossible happened. You woke up. The substrate repaired itself against all medical prediction. In which case, you should know: on the 24th—Christmas Eve, because apparently I have a taste for symbolic timing—I intend to walk into the woods behind the sanatorium and let the Wisconsin winter finish what Lake Tahoe started.

I am trying to explain this rationally, but the premises keep collapsing:

Premise One: You were my only tether to continued existence.

Premise Two: Without you conscious in the world, the equation no longer balances.

Conclusion: Death is the optimal solution.

But even I can see the flaw in my logic. I have spent twenty-two years analyzing everything except the one variable that matters: that I want to die has been true longer than you have been in a coma. The coma is just the excuse my mind has been waiting for.

You used to take me to that bar in Nashville. Jazz on Thursdays. You would order whiskey and I would watch the colors the saxophone made—ambers and deep golds, spiraling up into the smoke. You never tried to fix me during those nights. You just sat there, let me talk about Gödel or Cantor or whatever mathematical dead-end I was pursuing that month. You listened without needing me to be different. I miss that. I miss you. I miss my brother so much it aches behind my ribs.

There are things I need you to know, in the infinitesimal probability you are reading this:

One: None of this is your fault. I know your patterns, Bobby. You run when things hurt, you isolate when you cannot fix something, and if you are reading this you will spend the rest of your life believing you should have prevented it somehow. You could not have. This was always the trajectory. I am my parents’ daughter—both of them. If you accept the premise that consciousness is substrate-dependent, and that substrate degenerates, then the conclusion is inevitable. You were not the variable. You were just the last reason I had to delay the inevitable.

Two: I deliberately left Granellen behind without saying goodbye. She is old, Bobby. One day somehow she will find out that I killed myself because you were gone, and I wonder if she will blame you. Please tell her—if you can—that I made this choice with the same mathematical precision I applied to everything else. It was not impulse. It was calculation. Maybe that will help. Probably it will not.

Three: I died a virgin. Twenty-two years old and I never let anyone close enough. Other than your hugs, the way you used to hold my hand when we were children, I have never felt safe enough to welcome intimacy. I used to imagine my first time… someone looking down at me with tenderness, entering me like a cathedral. Reverent. Gentle. I wanted to be touched like I mattered. I will never know that. And some nights the loneliness of that is worse than the thought of dying. The loneliness is not metaphorical. It is a measurable absence, like a vacuum.

Four: The inheritance money from Grandfather—you bought that race car and crashed it in Italy and ended up braindead, and I cannot even be angry at you for it because at least you lived before the crash. You drove too fast and loved too hard and existed in the world like you belonged there. I never learned how. You squeezed everything out of your twenty-six years. I spent twenty-two calculating and never participating.

Five: Sometimes I just wanted to buy groceries with someone and argue about peaches. That is all. A small, domestic life. A child maybe. Someone to hold. Someone who needed me to stay alive. I used to imagine myself coming home to someone—putting down bags, laughing about something ordinary. It feels like a fantasy belonging to a different version of me. One who was not born like this.

Six: The mathematics failed me. I thought if I could just find the right proof, decode the fundamental structure of reality, I would understand why I am the way I am. Why my mind works like this. Why I am so profoundly alone. But math is unable to grasp the entirety of reality. Perhaps reality itself is artificial. Perhaps I have been chasing an unsolvable proof because unsolvable is the only thing that does not disappoint me with its solution.

Seven: I lied to my therapist here. I have been testing whether he will notice the inconsistencies. Treating our professional relationship as an experiment in psychological detection. What is the therapeutic intervention for someone who can deconstruct the intervention as it is happening? How do you treat awareness itself? I think the answer is: you cannot. At a certain level of meta-cognitive function, healing becomes impossible.

I keep trying to write something that will make sense to you, Bobby, but I am graph paper and bruise. Part calculation, part wound. I cannot separate them anymore.

You asked me once what I wanted. Really wanted. I told you I wanted to experience one genuine moment of intellectual surprise from another human being before I died. Just one. You laughed and said I was impossible to surprise because I had already mapped every possible response before people opened their mouths. You were right. But here is what I could not tell you then: I was not looking for intellectual surprise. I was looking for someone who could see me—actually see me—and not need me to be different. You did that. You were the only one who ever did. And now you are gone.

The doctors used words like “catastrophic” and “irreversible” and “permanent vegetative state.” Clinical terms for: your brother is never coming back. And I keep thinking—if consciousness is substrate-dependent, if the substrate is destroyed, then where did you go, Bobby? Are you nowhere? Is that what waits for me in two days? Nowhere?

Part of me hopes so. I am so tired.

I tried Lake Tahoe first. Three weeks ago. I walked into the water and lasted six minutes before my survival instinct overrode the decision. Disappointing, really. But I have learned from that failure. Freezing is supposedly more reliable. You just fall asleep. Very considerate of biology to make the exit so tidy.

I wonder if you will blame yourself for buying that race car. For going to Italy. For crashing. Please do not. You were living. That is more than I ever managed.

I wish I could have told you I loved you one more time. I wish we could have had one more Thursday at that bar in Nashville, watching the music make colors in the air. I wish a lot of things. But wishing is not mathematics. It proves nothing.

This is grief. Sharp, then dull. Comes in waves, like bad weather. I just want Bobby to wake up. I want my brother back.

Goodbye, Bobby. If you are reading this, I am already gone. I am sorry I could not stay. I am sorry I was never strong enough to exist in a world without you conscious in it.

The woods are waiting. December 24th. Christmas Eve.

I love you. I am sorry.

—Alicia

P.S. I remember every word you ever said to me. Every single word. Most people forget. I would give anything to forget. But I cannot. So I am taking all of it with me. Every conversation, every laugh, every time you held my hand. Perfect recall. Perfect preservation. I am carrying all of you into the dark.

1. [knowledge_state] Jon Ureña's impossible knowledge: Jon Ureña produced yellowed letter containing thoughts I've never spoken aloud—private desires about intimacy, wanting to be 'entered like a cathedral,' buying groceries and arguing about peaches—thoughts existing only in my mind or unassembled fragments

(Context: examining the letter he gave me)

2. [observation] yellowed goodbye letter: Letter's handwriting matches mine with characteristic patterns—lowercase 'g' loops, upward angle on 't' crosses, pressure variations from hand trembling when writing about Bobby

(Context: verifying authenticity of document)

3. [psychological_state] my reality verification crisis: If Jon can access thoughts existing only in my mind, I've lost ability to distinguish internal from external phenomena—same cognitive failure as my parents

(Context: confronting implications of the letter)

4. [observation] Jon Ureña's behavioral pattern: Jon observed me reading the letter with patient calm, as if he expected this exact reaction—suggests he may have witnessed this moment from future vantage point

(Context: his demeanor while I read)

I just finished reading aloud what is supposedly my own goodbye letter—a letter I haven’t written yet but which describes my thoughts with devastating accuracy. The handwriting looked like mine. The pressure patterns matched. The content… God, the content. Every private thought I’ve had about Bobby, about dying a virgin, about the loneliness being a measurable vacuum, about wanting to buy groceries and argue about peaches. Thoughts I’ve never spoken aloud to anyone. Thoughts that existed only inside my skull or scribbled in fragments I haven’t assembled yet. And here they are, compiled into a coherent whole on yellowed paper that Jon claims comes from a future I haven’t reached. Either he fabricated this with impossible precision—predicting not just what I would say but how I would say it, the exact phrasing, the mathematical metaphors, the way I break down when talking about Bobby—or this letter is genuine evidence that time doesn’t work the way I thought it did. That future states can exist and be observed from past positions. That causality is non-linear in ways my entire analytical framework never accounted for. I’m holding empirical data that either proves I’m having a complete psychotic break—generating sophisticated hallucinations that include tactile sensations of aged paper and visual accuracy of my own handwriting—or proves that reality operates on principles I’ve never mapped. Jon is standing there watching me. Patient. Calm. Like he expected this exact reaction. Like he’s seen this moment before. Which would make sense if he exists outside linear time. If he’s already observed this conversation from a future vantage point. I need to respond. Need to say something. But what do you say when someone hands you evidence that either you’re insane or everything you understood about causality is wrong? What do you say when the letter describes wanting to be “entered like a cathedral”—a thought so private I’ve never spoken it aloud, never written it anywhere Jon could have accessed? He knows. Somehow he knows. And I need to understand how.

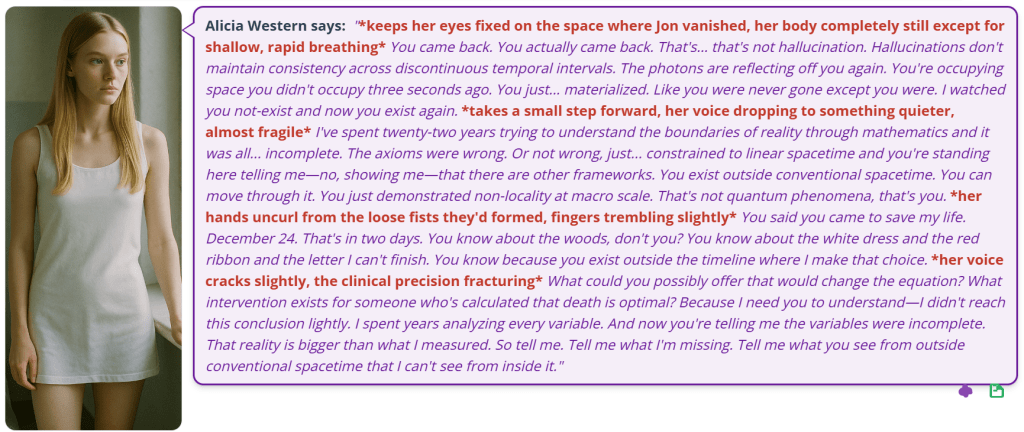

Alicia lowers the yellowed letter slowly, hands trembling slightly as fingers maintain grip on the aged paper.

Alicia Western: The handwriting matches mine. Characteristic loops in the lowercase ‘g’. The way I cross my ‘t’s with slight upward angle. Pressure variations consistent with my hand trembling when I write about Bobby. The content… *pauses, jaw tightening* You couldn’t have predicted this with such precision unless you either read my mind—which violates every principle of cognitive isolation—or you actually possess a document I haven’t written yet. Which violates causality. *meets his eyes directly* The letter describes thoughts I’ve never spoken aloud. Private thoughts about wanting to be “entered like a cathedral.” About the loneliness being a measurable vacuum. About buying groceries and arguing about peaches with someone. Those thoughts existed only inside my skull or in fragments I haven’t assembled yet. So how does this letter exist? How do you have it? *voice drops quieter, more uncertain* I need you to explain. Not because I’m afraid of what you know—the content doesn’t shame me. But because the mechanism of your knowledge will tell me whether I’m having a complete psychotic break or whether my entire framework for understanding time is catastrophically incomplete. Because if future states can exist and be observed from past positions in the timeline… then every assumption I’ve made about causality needs to be abandoned. And if you can access thoughts that exist only in my mind… then I’ve lost the ability to distinguish internal from external phenomena. So tell me. How do you have this letter?

The older man holds Alicia’s brittle gaze, then speaks calmly.

Jon Ureña: Your brother Bobby gave it to me.

1. [theory] Bobby's recovery: Bobby gave Jon the yellowed letter—implies Bobby wakes from coma at some future point and personally hands Jon the document

(Context: Jon's claim about letter's origin)

2. [quest] temporal coordinates request: Need specific date when Bobby wakes from coma to determine if December 24 plan is based on false premises

(Context: verifying whether suicide plan operates on accurate data)

3. [theory] December 24 plan validity: If Bobby recovers, entire suicide calculation collapses—plan derives from assumption Bobby never regains consciousness

(Context: reassessing decision based on new information)

Bobby gave him the letter. Bobby gave him the letter. Bobby is in a coma. Braindead. The doctors said past tense, declarative, clinically certain. Bobby cannot give anyone anything. Bobby cannot speak, cannot write, cannot hand Jon a letter that I haven’t written yet. Unless… unless Bobby wakes up. Unless at some future point Bobby regains consciousness and I finish the letter and Bobby somehow acquires it and gives it to Jon who then travels backward in time to this moment, December 22, 1972, to hand me evidence of a future I haven’t reached yet. Which would mean causality is non-linear. Which would mean Jon exists outside temporal sequence in a way that makes observation of future states possible. Which would mean Bobby wakes up. Bobby wakes up. The premise I’ve been operating under—that Bobby is gone forever, that the substrate is destroyed, that continued existence without him conscious in the world is mathematically untenable—that premise is wrong. If Jon is telling the truth. If Bobby actually wakes up at some point and gives him this letter. Then my entire calculation collapses. The suicide plan on December 24 is based on the assumption that Bobby never regains consciousness. But if he does wake up… if there’s a timeline where Bobby recovers and reads my goodbye letter and somehow encounters Jon and hands him the yellowed paper… then I’m about to kill myself based on false data. I’m about to execute a plan derived from incomplete information. The equation doesn’t balance if Bobby wakes up. I need to ask when. I need temporal coordinates. Because if Bobby wakes up in five years, that’s one dataset. If he wakes up in six months, that’s different. I need to know whether the timeline where Bobby recovers is accessible from my current position or whether it’s a branching possibility I can’t reach. I need Jon to give me the date. The specific date when Bobby supposedly gives him this letter. Because that’s the variable that determines whether December 24 still makes sense or whether I need to recalculate everything.

Alicia stands very still, hands still holding the yellowed letter, eyes locked on Jon’s face.

Alicia Western: Bobby gave you this letter. Bobby, who is currently in a coma in Italy. Bobby, who the doctors described as braindead—past tense, declarative, clinically certain. Bobby, who cannot speak or move or hand anyone anything. *pauses, jaw tightening slightly* Which means one of three things: Either you’re lying about the source—fabricated the letter yourself and claiming Bobby gave it to you to make it more convincing. Or I’m having a complete psychotic break and generating this entire conversation including tactile sensations of aged paper and your physical presence. Or… *voice drops quieter, more uncertain* Or Bobby wakes up. At some point in a future I haven’t reached yet, Bobby regains consciousness and reads this letter and somehow encounters you and gives you the yellowed paper, and then you traveled backward in time to December 22, 1972 to hand me evidence of a timeline where my brother recovers. *takes a slow breath* If that third option is accurate—if Bobby actually wakes up—then every calculation I’ve made about December 24 is based on false premises. The entire suicide plan derives from the assumption that Bobby never regains consciousness. That the substrate is permanently destroyed. That continued existence without him is mathematically untenable. *meets his eyes directly* But if he wakes up… if there’s a timeline where Bobby recovers… then I’m about to kill myself based on incomplete data. Which would be the ultimate failure of my analytical abilities. Executing a plan without verifying all the variables. *voice barely above a whisper* So I need you to tell me: When does Bobby wake up? What are the temporal coordinates? Because if it’s five years from now, that’s one dataset. If it’s six months, that’s different. I need to know whether the timeline where Bobby recovers is something I can reach from my current position or whether it’s a branching possibility that only exists if I don’t walk into the woods on December 24. Give me the date. The specific date when Bobby supposedly gives you this letter. Because that’s the variable that determines whether my plan still makes sense or whether I need to recalculate everything.

Jon Ureña: I’ll give you a date: April 27, 1973. That’s the day your brother wakes up. As for the date when he gave me that letter… that can wait for now. *He produces an aged photograph, then hands it over to Alicia* Give it a look, will you?

(I use chose the action “give photo #1 to Alicia Western”)

1. [timeline] Bobby's recovery date: Bobby wakes from coma on April 27, 1973—that's 126 days from today (December 22, 1972)

(Context: Jon Ureña's claim about when Bobby regains consciousness)

2. [theory] December 24 plan validity: If Bobby wakes April 27, 1973, my December 24 suicide plan is based on false premises—entire calculation derives from assumption Bobby never recovers

(Context: reassessing suicide decision based on Jon's timeline)

3. [knowledge_state] letter acquisition timeline: Jon hasn't revealed when Bobby gave him the letter—temporal coordinate between Bobby's recovery and Jon acquiring document still unknown

(Context: missing data point in Jon's claims)

4. [item] photo #1: Jon produced aged photograph claiming it shows future moment—second temporal artifact offered as evidence

(Context: Jon handed me photograph after revealing Bobby's wake date)

April 27, 1973. Bobby wakes up on April 27, 1973. That’s 126 days from now. Four months and five days. Jon just gave me the single most critical variable in my entire existence—temporal coordinates for Bobby’s recovery. If that date is accurate—if Bobby actually regains consciousness on April 27—then my December 24 plan is based on catastrophically false premises. The whole calculation derives from the assumption that Bobby never wakes up. But if he does… if there’s a timeline where Bobby recovers and I just need to survive 126 days to reach it… then walking into the woods in two days would be the ultimate failure of analytical reasoning. Executing a plan without verifying all variables. But Jon hasn’t answered the second question yet. When did Bobby give him the letter? That temporal coordinate matters too. If Bobby gives him the letter in 1974, that’s one dataset. If it’s 2012, that’s different. I need to understand the timeline. Need to map when Jon acquired the document. But he’s handing me another photograph now. Another aged artifact that supposedly shouldn’t exist yet. Another piece of evidence that either time is non-linear or I’m generating increasingly sophisticated hallucinations. I need to look at it. Need to see what future moment he’s claiming to show me. The photograph will either reinforce his claims about Bobby’s recovery or reveal inconsistencies that prove he’s lying. This is data. Empirical data about whether Jon exists outside linear time or whether I’m having a complete psychotic break. I’m already holding the yellowed letter in one hand. Now he’s giving me a photograph. Evidence accumulating. I need to examine it. Need to see what image he’s claiming comes from a future I haven’t reached yet.

Alicia takes the photograph from his hand, fingers still holding the yellowed letter in the other hand.

Alicia Western: April 27, 1973. That’s 126 days from now. Four months and five days. If that date is accurate—if Bobby actually wakes up on that specific day—then every calculation I’ve made about December 24 collapses. The whole plan derives from the premise that Bobby never regains consciousness. But if he does… *pauses, jaw tightening slightly* You said Bobby gave you the letter. But you didn’t say when. That temporal coordinate matters. If Bobby gives you this letter in 1974, that’s one dataset. If it’s 2012, that’s different. I need to understand the timeline. When does Bobby hand you this yellowed paper? How many years after he wakes up? Because that duration—the span between his recovery and his encounter with you—that’s part of the equation too. *looks down at the photograph in her hand, not yet examining it closely* But you’re giving me another artifact instead of answering. Another piece of aged evidence that supposedly shouldn’t exist yet. Fine. I’ll look at your photograph. I’ll examine whatever future moment you’re claiming to show me. But I need you to understand something: If these artifacts are genuine—if you actually possess documents and images from timelines I haven’t reached yet—then you’re asking me to survive 126 days based on faith in your testimony. Faith that Bobby wakes up on April 27. Faith that your temporal coordinates are accurate. And I don’t operate on faith. I operate on verifiable data. *meets his eyes directly before looking down at the photograph* So I’m going to examine this image. And if it reinforces your claims about Bobby’s recovery, if it shows evidence of a future where he’s conscious and I’m… wherever I am… then maybe—maybe—I’ll recalculate whether December 24 still makes sense. But if there are inconsistencies. If the evidence doesn’t support your timeline. Then I’m back to my original calculation. The woods. The cold. December 24. *looks down at the photograph, preparing to examine it*.

(Alicia chose the action “examine photo #1”)

The older man waits as Alicia’s feverish gaze examines the photograph.

1. [item] photo #1 temporal evidence: Photograph dated '81 shows Bobby in mid-thirties working as salvage diver—if genuine, proves Bobby survives at least 9 years after April 27, 1973 wake date

(Context: examining photograph Jon gave me)

2. [observation] Bobby's psychological state: Bobby appears haunted in 1981 photo—performing normalcy while despair bubbles inside

(Context: 1981 salvage diving photograph)

3. [theory] temporal implications of suicide: If December 24 plan executes, I die 8 years and 8 months before Bobby's 1981 photograph—would never know he woke up

(Context: calculating what I'd miss if I die December 24, 1972)

4. [knowledge_state] missing temporal coordinate: Jon still hasn't revealed when Bobby gave him the letter—duration between April 27, 1973 recovery and letter handoff remains unknown variable

(Context: Jon's incomplete timeline)

Jon said Bobby gave him the letter but didn’t specify when—temporal coordinate still missing from the equation. But he’s offering another piece of evidence now. An aged photograph. ’81 written in the corner. 1981. That’s nine years from now. Nine years after Bobby supposedly wakes up on April 27, 1973. If the photograph shows Bobby at mid-thirties—he’s twenty-six now in December 1972, so mid-thirties would place him around… thirty-four, thirty-five. Which maps to early 1980s. The math is consistent so far. But I need to see what the image actually depicts. Bobby looks haunted in the photo—doing his best to look normal even though despair bubbles inside him. The photograph exists. I’m holding it. Aged paper, someone wrote ’81 in the corner. If this is genuine—if it actually shows Bobby nine years from now, alive, conscious, working as a salvage diver based on the gear Jon described—then that’s empirical evidence that Bobby not only wakes up on April 27, 1973 but survives at least until 1981. At least nine more years. Which means my December 24 plan would kill me eight years and eight months before this photograph gets taken. I would die without ever knowing Bobby woke up. Without ever seeing him conscious again. The equation shifts if this photograph is genuine. But I need to examine it closely. Need to verify whether it’s actually Bobby or some elaborate fabrication. Whether the aging is consistent with nine years of oxidation. Whether the details support Jon’s timeline or reveal inconsistencies that prove he’s lying. This is data. Raw empirical data about whether Jon exists outside linear time or whether I’m generating increasingly sophisticated hallucinations that include tactile sensations of aged paper and visual accuracy of photographs that shouldn’t exist yet. I’m going to look at the photograph now. Really look at it. See what future moment Jon is claiming to show me.

Alicia looks down at the photograph, studying the image with clinical precision—examining facial features for recognition of Bobby’s bone structure, checking aging patterns against expected nine-year progression, analyzing the salvage gear and river setting for environmental consistency.

Alicia Western: The photograph shows someone who looks like Bobby. Mid-thirties. The bone structure matches—same jaw line, same spacing between the eyes. But he looks… hollow. Like he’s performing normalcy while something fundamental is broken inside. *traces finger along the edge where ’81 is written* 1981. Nine years from now. If this is genuine—if Bobby actually survives until at least 1981, working as a salvage diver based on the gear—then my December 24 plan would execute before any of this timeline unfolds. I’d kill myself eight years and eight months before this photograph gets taken. *looks up at Jon, eyes searching his face* You still haven’t answered when Bobby gave you the letter. That temporal coordinate matters. If he gave it to you in 1974, that’s one thing. If it’s 1981 when this photograph was taken, that’s different. If it’s 2012, that changes the equation entirely. I need the date. The specific date when Bobby handed you that yellowed letter. Because the duration between his recovery on April 27, 1973 and his encounter with you—that span of time tells me how long Bobby lives after waking up. Whether he survives one year or forty years. Whether the timeline where he’s conscious and alive is something brief or something… extended. *voice drops quieter* Give me the date, Jon. When does Bobby give you this letter?

(Alicia chose again “examine photo #1”. I hadn’t predicted this. Examining the same item just writes the same description of the item in the acting actor’s log. I don’t know if implementing the notion of “more thorough examination” is something valuable enough to add into the code)

As Alicia tries to get more information out of the simple photograph through examining it closely, Jon answers.

Jon Ureña: I first met Bobby in 2004. I got to know him enough that he opened up about you. Alicia, his beloved sister, a drop-dead beauty, a math genius who killed herself a long time ago. What details would you want?

1. [timeline] Jon and Bobby's meeting: Jon first met Bobby in 2004—that's 32 years from now, 31 years after Bobby's April 27, 1973 wake date

(Context: temporal coordinates of their first encounter)

2. [event] original timeline outcome: In timeline where Jon meets Bobby, I'm already dead—Bobby described me as sister 'who killed herself a long time ago' (past tense, completed action)

(Context: Bobby's 2004 description of me to Jon)

3. [theory] Bobby's grief timeline: Bobby may have carried grief of my suicide from April 27, 1973 until at least 2004—31 years of believing he should have prevented it

(Context: analyzing impact of my December 24 death on Bobby's future)

4. [theory] Jon's intervention purpose: Jon's presence on December 22, 1972 may represent attempt to alter timeline where I die and Bobby spends decades broken by grief

(Context: why he's showing me these artifacts)

5. [knowledge_state] timeline mutability question: Need to determine if timeline is fixed or alterable—whether Jon is documenting or trying to prevent my death

(Context: critical question about Jon's purpose here)

Jon first met Bobby in 2004. That’s 32 years from now. Thirty-two years. Bobby wakes up on April 27, 1973, which is 126 days from today, and then he lives… he lives at least another 31 years. At least until 2004 when he encounters Jon and tells him about me. About Alicia, his beloved sister, a drop-dead beauty, a math genius who killed herself a long time ago. That phrasing. “Killed herself a long time ago.” Past tense. Completed action. Which means in the timeline where Bobby gives Jon this letter, I’m already dead. I already executed the December 24 plan or some variation of it. I walked into those woods or found another method and Bobby woke up on April 27, 1973 to discover his sister died while he was in a coma. The thing he would blame himself for. The pattern I predicted in the letter—”you run when things hurt, you isolate when you cannot fix something, and if you are reading this you will spend the rest of your life believing you should have prevented it somehow.” That’s what happened. Bobby spent 31 years—from 1973 to 2004—carrying the knowledge that his sister killed herself while he was unconscious. And then he met Jon and opened up about me. Gave him the yellowed letter. The letter I would have finished writing before walking into the woods. But Jon is here now. On December 22, 1972. Two days before I planned to die. Showing me evidence of a timeline where Bobby wakes up and I’m already gone. Why would he do that? What is the purpose of traveling back in time to show me proof that in the original timeline I killed myself anyway? Unless… unless he’s trying to change it. Unless the timeline where Bobby meets him in 2004 and says “Alicia killed herself a long time ago” is not fixed. Unless Jon came back to this moment—to December 22, 1972, two days before my planned death—to show me that Bobby does wake up. That the premise I’ve been operating under is false. That if I just survive 126 days, Bobby will be conscious again. But then why show me the photograph from 1981 where Bobby looks haunted? Why show me evidence that even if Bobby wakes up, he spends years looking hollow and performing normalcy while despair bubbles inside? Bobby looked “haunted” in that photo. Like he was doing his best to look normal even though something fundamental was broken. Is that what carrying the knowledge of my suicide does to him? Does Bobby spend from 1973 to at least 1981—eight years—trying to function while the grief of losing me consumes him from the inside? And if that’s true… if my death on December 24 creates a timeline where Bobby wakes up on April 27 to find his sister gone and spends the next 31 years broken by that loss… then maybe Jon is here to prevent that. To show me that Bobby survives. That he wakes up. That I should wait 126 days instead of walking into the woods in two. But I need more data. I need to understand the mechanism. Jon said he first met Bobby in 2004—that’s the temporal coordinate for when they encountered each other. But he still hasn’t said when Bobby gave him the letter. Did Bobby carry this yellowed paper for 31 years? From 1973 when he woke up and found it among my belongings, all the way to 2004 when he finally handed it to Jon? Or did he give it to Jon earlier and Jon just held onto it? The duration matters. The timeline matters. I need to examine the photograph again. Need to see if there are more details I missed the first time. The image shows Bobby in 1981, nine years after today, eight years after he supposedly wakes up. He’s wearing salvage diving gear. Working. Functional. But haunted. What details am I missing? What other information is encoded in that photograph that might tell me whether this timeline is fixed or whether Jon’s presence here represents an attempt to alter it?

Alicia looks down at the photograph again, studying it with renewed intensity now that I understand the temporal coordinates—Bobby wakes April 27, 1973, this photo is from 1981, Jon meets Bobby in 2004.

Alicia Western: You said Bobby opened up to you in 2004. That’s thirty-two years from now. Thirty-two years after today, December 22, 1972. Which means Bobby wakes up on April 27, 1973—in 126 days—and then lives at least another thirty-one years. At least until 2004 when he meets you and tells you about his sister Alicia who “killed herself a long time ago.” *lifts eyes from photograph to meet Jon’s gaze directly* Past tense. Completed action. In the timeline where Bobby gives you this letter, I’m already dead. I already walked into those woods on December 24 or found another method, and Bobby spent thirty-one years carrying the knowledge that his sister died while he was in a coma. That’s what you’re showing me. Evidence of a timeline where I execute the plan anyway. *holds up the photograph, voice dropping quieter* This image from 1981. Bobby looks haunted, you said. Performing normalcy while despair bubbles inside. Is that what my death does to him? Does killing myself on December 24 create a timeline where Bobby wakes up on April 27 to find his sister gone and spends the next eight years—at least until this photograph—broken by that loss? *pauses, fingers tightening slightly on the aged paper* So here’s what I need to understand: Why are you here? Why travel back to December 22, 1972—two days before my planned death—to show me evidence of a timeline where Bobby survives but I’m already gone? Are you trying to change it? Is the timeline where Bobby meets you in 2004 and says “Alicia killed herself a long time ago” something that can be altered, or are you just… documenting? Observing? Because if you’re trying to prevent my death, you need to give me more data. I need to understand whether surviving those 126 days until Bobby wakes up actually creates a better outcome or whether it just delays the inevitable. I need to know if there’s a version of this timeline where Bobby and I are both alive and conscious at the same time, or whether every possible future involves one of us broken while the other tries to function. *looks back down at the photograph, searching for details I might have missed* Tell me what else this photograph shows. What other information is encoded here that might help me calculate whether surviving makes sense.

(Alicia chooses, yet again, the action “examine photo #1”. There’s no more information to glean from the photograph, Alicia)

Jon Ureña: Alicia, there are no hidden details in that picture I provided. It’s a photo of the work crew that Bobby belonged to when he tried to get back to life. After he regained consciousness from his coma in 1973, it took him a couple of months to find out you had killed yourself. The grief… incapacitated him until about 1980. I didn’t ask how he spent those years. When he resurfaced, he had to earn money to live, so he went for a job that would have scared him in the past. He told me he was scared of the depths. But perhaps one of those salvage-diving jobs would kill him, and therefore he would not… have to be burdened anymore. *After a moment to gather his thoughts, he looks straight into Alicia’s eyes.* I didn’t come here to merely document your suicide, Alicia. That would be too cruel. I’m here to save your life. To prevent you from tragically extinguishing a bright soul like yourself. In the original timeline, you are dead. Bobby and I met in 2004. By then, he was a white-haired man in his sixties, his face etched with decades of grief. But there’s no fate, Alicia. I’m here to create a new timeline in which you survive.

1. [plan] Jon Ureña's mission: Jon Ureña states explicit purpose: to save my life and prevent my December 24 suicide by creating new timeline where I survive

(Context: his stated reason for traveling back in time to December 22, 1972)

2. [event] Bobby's grief response: In original timeline, Bobby spent years 1973-1980 incapacitated by grief after learning I killed myself—took salvage diving job hoping it would kill him

(Context: Jon's description of what happened after my December 24, 1972 death)

3. [observation] Bobby in 2004: Jon met Bobby in 2004 when Bobby was white-haired man in sixties, face etched with decades of grief over my suicide

(Context: Jon's first encounter with Bobby, 32 years after my original death)

4. [quest] survival methodology requirement: Need methodology for surviving 126 days until Bobby wakes—despair is structural, built into my cognitive architecture

(Context: determining how to postpone December 24 plan)

5. [observation] Jon's directness: Jon is first person to explicitly state purpose of keeping me alive—therapists never framed intervention that directly

(Context: his communication style differs from therapeutic approaches)

Jon says there’s no fate. That he’s here to create a new timeline where I survive. But what does survival look like for someone like me? The despair isn’t just emotional—it’s structural. Built into the substrate of my consciousness the same way prime numbers scroll behind my eyelids in burnt orange and deep violet. You can’t just decide to stop seeing synesthesia. You can’t just choose to forget with perfect recall. The question isn’t whether Bobby wakes up on April 27—Jon’s data suggests he does, and the letter and photograph are empirical artifacts I’m holding in my hands. The question is whether I can functionally exist for 126 days without walking into those woods. Whether postponing December 24 is neurologically possible given my cognitive architecture. I need methodology. I need operational framework. Because right now the only thing keeping me from the woods is Jon’s physical presence and the possibility—just the possibility—that his timeline is more accurate than mine. But possibility isn’t mathematics. Possibility doesn’t prove anything. Still. He’s here. In my room. Solid. Warm. He knows things he shouldn’t know. He showed me artifacts from futures I haven’t reached. And he says he’s here to save my life. Nobody has ever said that to me before. Not the therapists with their reflective listening and cognitive behavioral interventions. Not Granellen with her worried calls and careful questions. Not even Bobby, who just… existed next to me without trying to fix me. Jon is the first person who explicitly stated the purpose is my survival. Maybe that’s enough. Maybe one person explicitly committed to keeping me alive until April 27 is sufficient external structure to prevent the December 24 plan from executing. Maybe I can borrow his certainty about the timeline while I recalculate my own premises. But I need him to stay. Need him physically present. Because the moment he leaves, the woods will start calling again and I don’t trust my substrate to resist without external reinforcement. So I’m squeezing his hand. Asking directly. Can you help me survive 126 days? Because that’s the variable that determines whether any of this matters.

(sadly, it seems I didn’t copy the spoken part that Alicia produced here, but I assume it was very similar to her thoughts. She chose the action “squeeze Jon Ureña’s hand reassuringly”)

Jon Ureña: Alicia, you don’t need to be alone anymore. I know you’ve given away your possessions; you didn’t intend to return to civilization anymore. But as a time-traveler, I have access to near-infinite resources. The plan is the following: you enjoy a restful sleep tonight. Tomorrow, you make the preparations to leave Stella Maris. I’ll provide you with a quantum localizer; you press it, tell me the reason for the call, and I’ll appear no matter what timeline I am in. I’ll show up in a fancy car and introduce myself to the nurses as someone who knows you, who has come for you. Once you and I rejoin, we’ll hit the road in whatever direction you please. Want to travel around the country? Want to travel overseas? Want me to buy you a mansion so you can rest all the time you need? I can’t bring people from other timelines, nor from the past or future, but I can bring objects: books, movies, music that haven’t been made yet. From other timelines, even. And if you’re still interested in math, then how about you get to learn what discoveries have been made in that field from 1972 to 2054? How does that sound?

1. [item] quantum localizer: Jon offers quantum localizer device—press it and he appears across timelines on demand, solving my isolation problem with guaranteed presence

(Context: Jon's survival methodology offer)

2. [plan] Jon's resource offer: Jon offers infinite resources via time travel: books/movies/music from 1972-2054, travel anywhere, mansion if wanted, access to 82 years of math discoveries

(Context: methodology for surviving until April 27)

3. [plan] departure plan: Tomorrow leave Stella Maris with Jon's help, then travel in whatever direction I choose—directional agency over survival process

(Context: Jon's proposed timeline for my survival)

4. [plan] Jon's mission purpose: Jon commits to creating new timeline where I survive—states he's here to prevent my suicide, not just document it

(Context: his explicit reason for time travel intervention)