Mara covered the lens of her helmet with one palm, and slumped her shoulders. Jing backed away from the artifact, his fingers tightening around the pry bar. The woman took a breath. She made sure our eyes met.

“Perhaps it would help you to rest until we fly back. In the cockpit. Listen. When you loaded the material onto the ship, did you go aboard to check the radio?”

Was she asking me about communications now? What did it matter? Was she trying to annoy me?

“No, I didn’t check it,” I said dryly.

“Who knows how much time we have left. We’ll haul the remaining material as fast as we can, and figure out how to free this artifact.”

“Wait. You intend for us to take it?”

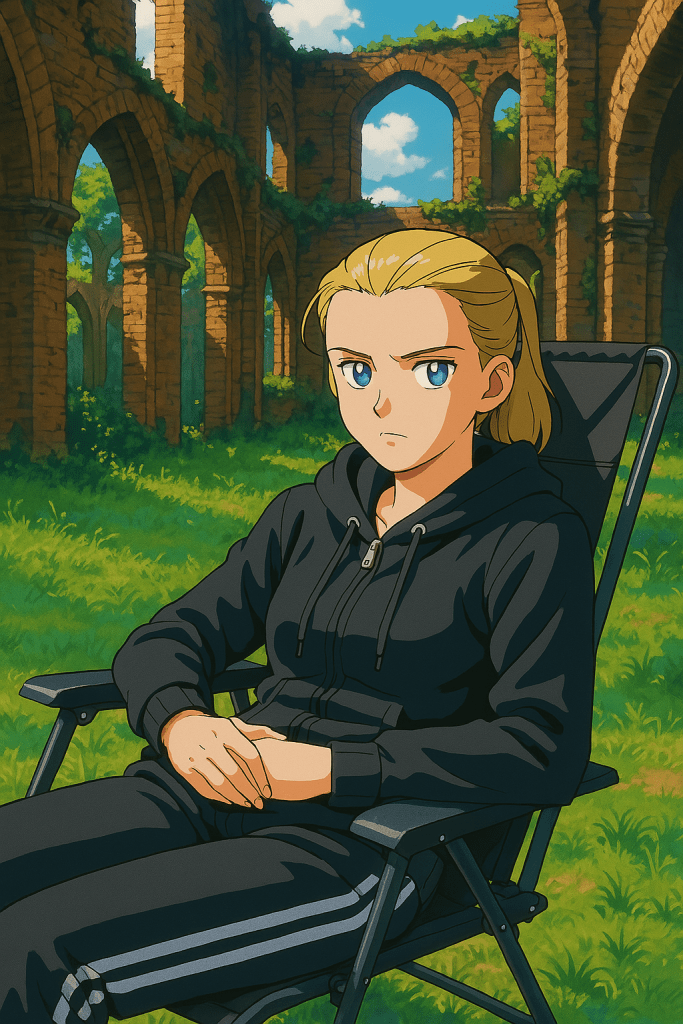

Mara confronted me with the cold anger that hardened her features whenever she spoke of her superiors.

“You promised me this outpost would contain unknown artifacts that would launch my career. I didn’t believe you, because you were basing it on fantasies, but you stumbled upon the truth by chance. This artifact will secure my career for the rest of my life. It will justify to everyone who meddles why we risked so much coming down to this planet.”

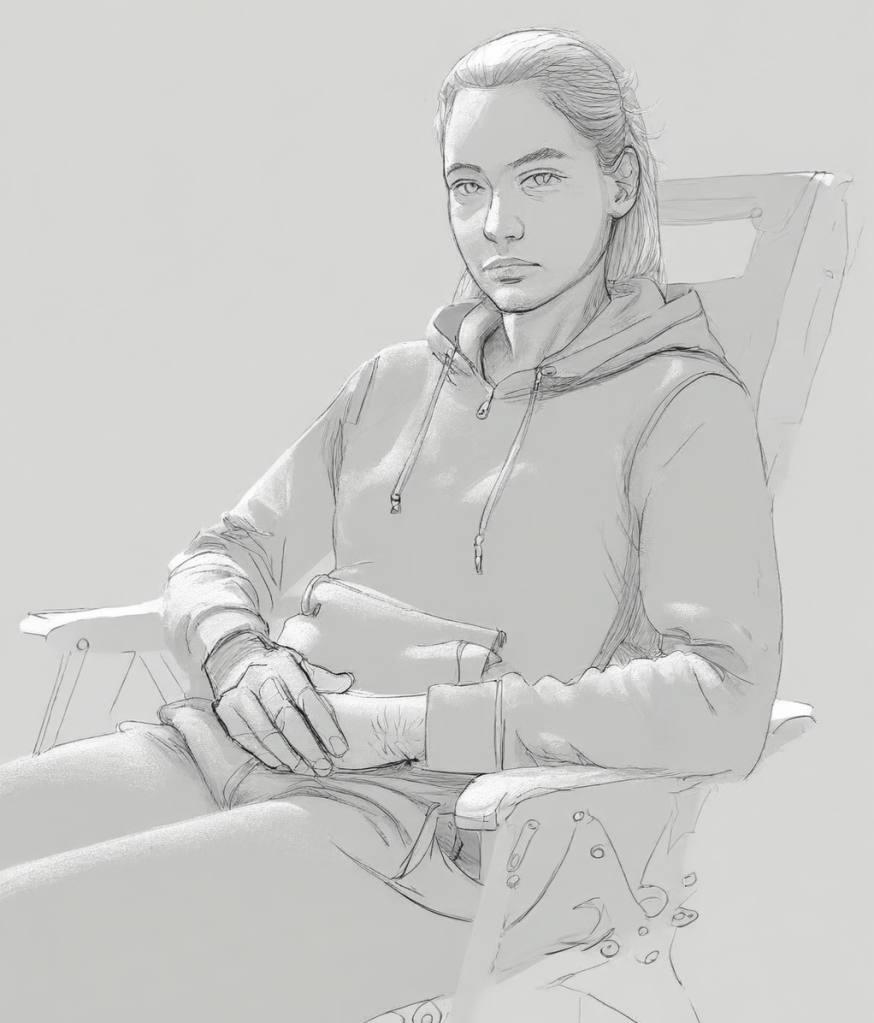

I leaned on the wall to push myself up, but the effort sent a jolt flashing through my brain. I stopped and clutched the side of my helmet. My heart was pounding. If I overloaded my limbs with commands, I risked my neurons short-circuiting.

I swallowed hard. Catching my breath, I faced Mara.

“Whatever that thing triggered feels like malice. You want to bring it up to the station and endanger thousands of people?”

“Kirochka, think. When we get back, you’ll need to file your report on the survey of this sector. Even if you avoid mentioning the artifact, another science team will explore this outpost and take the credit. Someone will get the artifact off this planet, and it’s going to be us.”

I felt dizzy, slick with cold sweat, as if I were incubating some disease. The shadows focused streams of insults and threats on me. I needed to flee, to get away from Jing and Mara drilling me with their stares.

“Fine.”

I took two steps toward the exit, but they were blocking it. I lowered my gaze to the polished rock floor, to my boot prints, and wanted to close my eyes, sink into blackness.

“Move aside, please.”

I glimpsed out of the corner of my eye Jing and Mara moving around a support strut, putting the artifact between themselves and me. I edged toward the doorway and stopped. The xenobiologist’s mouth hung slightly open, and the woman watched my movements disapprovingly, as if I had insulted her.

“Don’t repeat what I did,” I said. “Don’t press your face against the shell of that thing, don’t look inside.”

“I wouldn’t have done that in the first place,” Mara retorted.

“Once you’ve loaded the rest of the material onto the ship, we’ll figure out how to deal with this thing.”

Her voice took on a cold, professional calm.

“I understand you need to rest, but there’s barely any of the outdated tech left to dismantle.”

“Before you try to move the artifact, talk to me first. Please, Mara.”

She pursed her lips. Was there any emotion behind her icy eyes? Did my anguish matter to her?

And why should I care? You’re stupid, Kirochka. You live for risks, a genetic flaw that threatens everyone around you, one I’ve exploited to launch my career. I need you because you can pilot. Once I’ve got the artifact onto the station and they know I discovered it, I’ll forget you exist. You’ll go on getting drunk with your stupid friends, or tangling yourself in the sheets with that boyfriend of yours, and I’ll refuse to answer your calls. I’ll get this artifact off this planet whether you like it or not.

I blinked, trying to clear the sweat stinging my eyes. My legs were trembling. The shadows crept inch by inch along the sides of the room, flanking me, and when they reached me, they would crush the breath out of me in their embrace.

Jing placed a hand on Mara’s arm. She shot him an annoyed look. The xenobiologist gave me the kind of smile one might offer a terminally ill patient.

“Kirochka. That’s your name, isn’t it? If you need help, please, just ask. Anything. We’re in this together.”

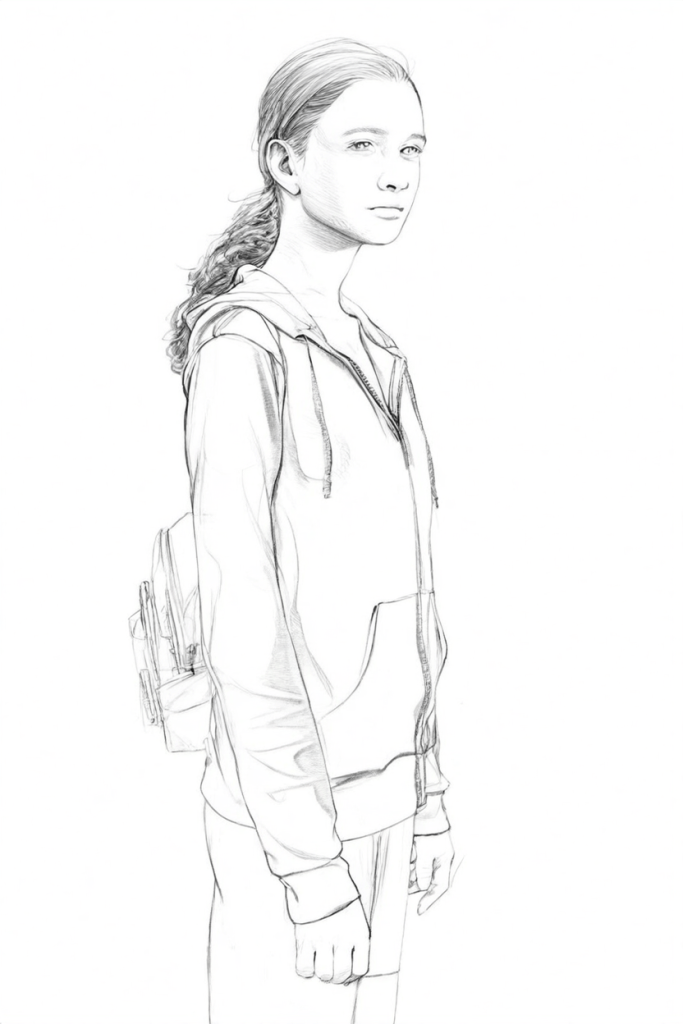

I nodded and turned away. I needed to get away from them. I crossed the basement, where the construction robots stood idle, following the oval beam of my flashlight as it slid across the floor. I ran up the ramp. As I moved away from the artifact, from Mara and Jing, the shadows receded, hanging level with me, trapped in the rock. If I stopped running and looked back, in the distance, the invisible eyes of a wall of silhouettes would watch me go. Seconds later, the shadows vanished as if I’d never felt them.

My leg muscles burned. Jing and Mara’s transmission, arguing about how to dismantle a construction robot, became choppy, then cut out as the indicator in my helmet lens showed I’d lost their signals.

I emerged outside and sprinted across the empty dome. Halfway across, I switched off my flashlight. When I exited onto the open ground outside, I bent over with my hands on my knees. Sweat spattered the inside of my helmet lens. I looked around, at the ring of slopes enclosing the crater, and the crags of the distant, looming mountains. How could I stand being cooped up in the ship’s cockpit waiting for Jing and Mara? I’d lie down on this sandy ground, out of sight, and give myself a few minutes to figure things out.

I hurried away from the landing site. A break in the terrain formed a small embankment. I jumped down into it. When I landed, my boots kicked up dust. I lay down on my side, careful not to put pressure on my oxygen recycler in case it came loose. Before me stretched nearly a kilometer and a half of wasteland ending in an upward slope.

Even though I was away from Jing, Mara, and the artifact, I was consumed by the anxiety that I’d made an irreparable mistake—an anxiety related to the moment when, taking a curve too tight, I’d crashed Bee, my racing ship, into an asteroid, and thought the collapsing cockpit had crushed my legs. That other consciousness crouched in my mind like a tarantula in its underground lair.

How could I have just left Mara and Jing down there? That woman needed to understand, to unravel mysteries. What if she copied me, thinking she could avoid my mistakes? If we took the artifact to the station, how long before someone else looked inside and discovered their reflection? Scientist after scientist would poke around, only to snap awake with their minds under siege.

But Mara was right. I would be forced to file the survey report for this sector. They’d collect the photos and topographical data in their databases. Even if the station found out about our illicit sortie, my friend would board the ship only once the artifact—the winning lottery ticket needed to stop her superiors stealing opportunity after opportunity from her—was waiting in the cargo hold.

What if I acted first, stopped this before we had to argue about it? I could destroy the artifact. Mara would hate me, maybe forever. She’d treat me with the same disdain she showed most people. But if I let that thing end up on the station, sooner or later the woman would convince herself she could study the undulating membranes without being affected.

I scraped my fingers through the sandy earth. Would I really destroy it? Yes. No matter how advanced the technology was, what good could come from something that materialized shadows projecting such hatred? I would smash that artifact, and it would spill onto the ground in a puddle of translucent, purple and pink matter, like a stranded jellyfish.

Author’s note: I wrote this novella in Spanish about ten years ago. It’s contained in the collection titled Los dominios del emperador búho.

You must be logged in to post a comment.