A South American man with toffee-colored skin, whose hair is shaved on the sides in zigzag lines that resemble the heartbeat on a monitor, is tending to the fryer, a contraption of polished steel. Using a pair of tongs, he plucks churros out of the bubbling oil and drops them into a paper cone, then he seizes a shaker of cinnamon sugar and sprinkles a dusting over the piping-hot, golden-brown pastries. The fry cook flashes a broad, white-toothed smile as he offers Jacqueline the bouquet of churros, but she’s busy rummaging through her purse for bills.

“Ma chérie, please grab it for me, will you?”

I stand on my tiptoes to receive the oil-stained cone, whose heat begins to seep into my palm and fingers. As I step back from the counter, the plume of steam that rises from the churros fills my nostrils with the aroma of fried, cinnamon-coated dough.

Jacqueline slips folded-up currency into the main snackman’s hand. Her fingers must have grazed his palm, because I sense him vibrate on an atomic level. Jacqueline, in turn, remains unfazed, as if accustomed to brushing up against filth.

The snack booth lord slides coins across the counter.

“Your change, miss. Thank you for gracing my stand with your beauty.”

My eyelids twitch. I’m tempted to slap the snackman in his stubbled face, but a criminal like that might pummel me back, so I focus on the cone of churros that burns in my grasp. I grab one of the cinnamon-dusted wands and bite off its end. As I chew on the crunchy crust, the soft interior melts on my tongue in a gush of sugary sweetness. Other than sex, such treats are the closest I will get to nirvana on this mortal plane.

From behind, an arm snakes around my waist and steers me toward the corner of the snack booth where Nairu, our Paleolithic child, is kneeling on the pavement in front of the bear-shaped garbage bin. The tip of her tongue protrudes from between her lips as she sketches in her sketchbook. When she notices us, she scrambles to her feet, flashes a triumphant grin, and holds out her drawing for us to behold.

Nairu’s fingers have smudged the black crayon across the page in rugged and earnest strokes, leaving rough-hewn edges and hasty shading, as if she had grappled with the concept of a bear-bin, trying to pin it down before it vanished forever. But unlike the resigned garbage bear, the eyes of her creation reflect wonder at the amusement park around it, and its mouth gapes in a frozen, silent laugh.

“Oh, that’s the loveliest garbage bin I’ve ever seen,” Jacqueline says.

“You have a keen eye, miss Paleolithic,” I say. “Each time you look at the drawing, the bear comes alive.”

Jacqueline’s fingers, tipped with almond-shaped nails, pinch the end of a churro. As she draws it out of the paper cone that I’m clutching, a miniature cascade of cinnamon sugar showers down.

“Here’s to our girl who sees art in every corner.”

Nairu’s eyes widen and her lips part at the sight of the approaching fried pastry. She exchanges the black crayon for the churro, then sinks her tiny teeth into the crust. As she chews, the pearly band of a smile spreads across her rosy cheeks. Given how we’re habituating her to pastries, in the future we may have trouble preventing her from rolling downhill.

We walk away from the snack booth, though my instinct urges me to hurry away like from a crime scene. The tattooed, ex-con concessionaire must be salivating at the masterpiece of Jacqueline’s derrière, because his voice follows us.

“Do come again.”

I throw a glance over my shoulder, ready to scowl at the snack-vending con-man. I’m searching for a sharper retort than “Not any time soon” when I realize that the stallman has ducked behind the counter, out of sight, as if struck by the weight of his sins.

We pass in front of a booth where two girls are leaning over to chase bobbing rubber ducks with hooked rods. On the interior walls, glossy plastic trinkets and plushies clamor for attention, forming a dense collage.

Jacqueline’s shoulder nudges mine.

“Our friend back there was quite taken with me,” she says in a teasing lilt. “The perils of making oneself devastatingly attractive.”

I want to scoff at the notion that such a lowlife, who probably served time for assault and robbery, could have become a friend of ours, but instead I gulp down the last of my churro, then suck the sugar clinging to my fingers.

“I can’t help feeling fear whenever someone flirts with my polymorphous girlfriend.”

Jacqueline lifts a hand to stroke the underside of my chin.

“If you could read my mind, love, you wouldn’t be insecure about it.”

Flushed with emotion, I fiddle with a button of my corduroy jacket.

“I don’t know if I would enjoy the attention from random, shady men.”

“It makes life much easier, that I can assure you.”

Clusters of fairgoers navigate the midway between carnival games and children’s rides: couples shepherding pre-teens, exchange students carrying backpacks and smartphones. The November sunshine glints off the screen at the end of a selfie stick. To the throng belongs the chatter, the click of shoes, the childish shouts and giggles of those who have grown accustomed to, and even thrive within, our shambling zombie of a civilization. In front of a bar, around a row of barrels used as standing tables, the patrons are brushing elbows, unaware of the looming apocalypse about to swallow their world. Who would listen if I were to explain, or scream, that the stars will fizzle out, that space-time will collapse on itself, that everything they know and love will be erased unless I stop it?

Some of the human beings present in this amusement park, let alone those I’ve come across since I was born, could be bosses who stress and overwork their employees; kids who torment other children out of boredom, or to exert dominance; parents who created life only to neglect it or even abuse it; modern marauders who stalk the streets to rob, rape, and kill; those who betray and destroy their own kind for power and profit. This world is filled with monsters, yet I must save them all.

How did Alberto, my former co-worker turned colossal blob of black sludge studded with eyeballs, put our problem? That I would come across the reality-altering machine, and I would recognize it. Those were his actual words, right? Damn it, why didn’t I write them down?! Surely I realized that to prevent the end of the universe, every word of the warning from that swamp-born bastard mattered. He did say, I’m almost certain, that I would recognize the machine as capable of tearing apart reality, so that excludes cars, computers, coffee machines, and whatnot. Ever since Alberto nauseated me with his presence, I’ve gone out of my way to suspect any device that may harbor gears or microchips, but the universe remains unsaved.

Let’s recap what I know: the professor, whom I’ve dubbed Dr. Weasel for all this rabbit-brained fuckery, must have constructed a labyrinthine construct where organic life is enmeshed with gears and cogs. Branching pipes terminate in leaves or in flasks bubbling with effervescent chemicals, while at the core of the contraption-organism rumbles a spider-legged mechanism wrought from neon-colored gems and spinning axles.

My chest constricts, a band of anxiety tightening around my ribs. I loosen my jaw, and find myself reaching for the comfort of a churro, but I grasp air. Did I drop the paper cone? Wait, where are mommy and my antediluvian daughter?

I’m standing close to a postcard rack that belongs to the souvenir stand. Up ahead, between the hotel and the stairs that lead to the rollercoaster, I spot Jacqueline’s figure, wearing a camel-colored suede blazer along with dark denim jeans that accentuate her curves. She’s nibbling on a churro while her other hand holds the remaining bunch. Beside her, Nairu, the sketchbook tucked under one arm, is mouthing words as she points up toward the tower.

When I take a step forward, a current crackles up my limbs, igniting every nerve. The cacophony of the amusement park stops, making my ears ring with sudden quiet. The brightness of a clear morning has switched to night as if cosmic spider legs had plucked the sun out of the sky.

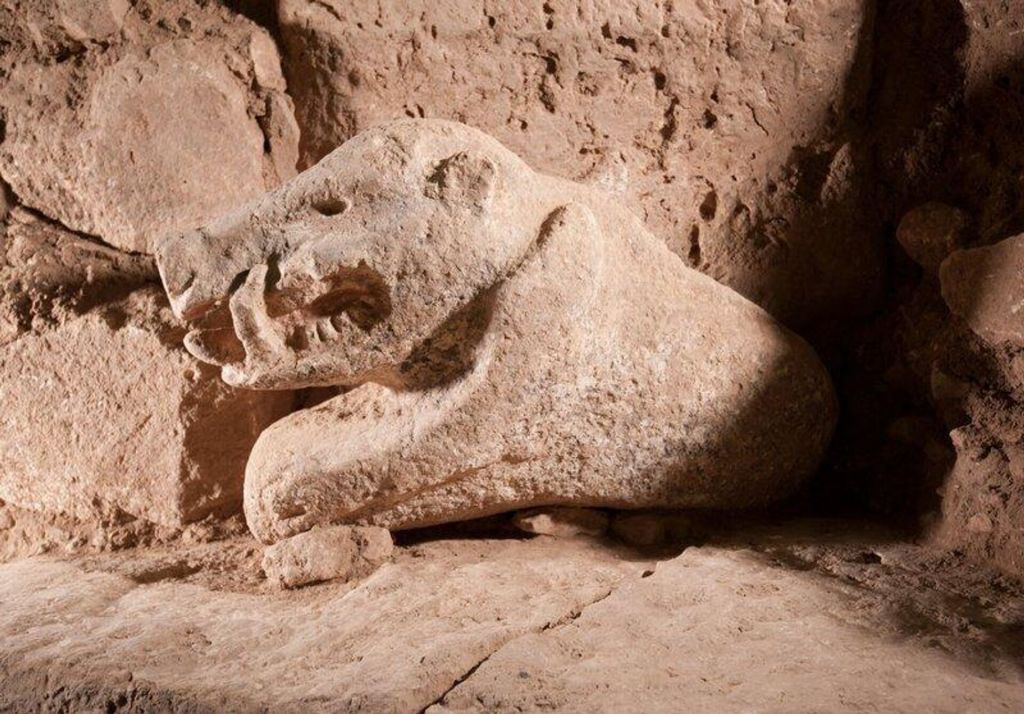

I’m standing at the back of a sunken, circular enclosure about twenty meters in diameter, whose walls are made out of stacked, rough slabs of stone. In the center, between a pair of towering, T-shaped pillars, an old man’s white hair and beard catch the sway of torchlight. He’s addressing the group before him as he gestures toward the night sky, a canvas sprawled with a myriad stars, in which the full moon casts a silvery glow. The men are garbed in animal hides and furs, and as necklaces, they’re wearing threaded beads and fangs.

Closer to me, sitting cross-legged by a crackling campfire, a wiry young man is scraping a hide with a flint knife. Kneeling on the other side of the fire, among strewn bones, a man wrestles with the heat and bulk of a huge bull’s innards. He’s scooping out glistening clumps of viscera and dropping them onto a steaming pile. The butcher groans, pushes himself upright, and takes a gulp from a swollen waterskin while thick blood and fat dribble down his arms. Above, perched upon the earthen rim of the enclosure, a male silhouette outlined in silver, etched against the splash of stars, leans on his spear, surveying the horizon.

The cold air carries the thick smells of burning logs, animal hides, sweat, damp earth, fresh rain on stone, nearby flora, and blood.

Rising five meters high at the center of the enclosure, the pair of T-shaped pillars are painted malachite green, their surfaces carved in relief with humanlike features: from the upper portion of the broad sides, deep-red arms reach down to rest their hands on the narrow side, above a belt adorned with black and white patterns that cinch the stone’s girth. Flickering torchlight pools shadows in the grooves of the reliefs, making the humanlike features pulse in a chiaroscuro effect.

The silhouettes of smaller pillars stand as sentinels around the perimeter of the enclosure, and on those bathed in torchlight, a menagerie of animals emerges: jet-black bulls, rust-red foxes, burnt-orange felines, alongside snakes, gazelles, vultures, scorpions.

I notice a statue to my right, tall as a basketball center, close as if it had sneaked up to me in the darkness. The eyes of that bearded face stare blindly from their sunken sockets. In its emaciated torso, the artist has sculpted each rib of the protruding ribcage. The statue’s hands are clutching its erect penis.

My insides explode with a surge of adrenaline and dread.

“Fuck no,” I blurt out.

The old man falls silent, and breath steams from his agape mouth. The group before him scrambles about, colliding with one another. Their torches send across the enclosure waves of light that elongate and warp human shadows into grotesque shapes. Pairs of eyes reflect the flames before fading into the darkness as their owners turn their heads in shared bewilderment. The silhouetted guard on the earthen rim brandishes his spear, whose point glints in the moonlight. The wiry man, frozen mid-scrape, stares up at me with wide-eyed awe. The butcher, his face a grimy mask of ash, tries to back away but slips on coils of intestine, crashing onto the carcass of the bull in a spray of gore.

“I ain’t doing this shit again,” I say. “Later, you guys. Good luck with civilization.”

I step back, and static electricity zaps through my body. The amusement park engulfs me in a burst of colors and noise.

I squeeze my eyes shut to shield them from the morning sunlight. My face has gone cold, my arms tingle with pent-up energy.

“There you are, mon amour,” Jacqueline says, her voice tinged with relief. “We lost you for a moment.”

When I open my eyes, I see Nairu with her cheeks puffed up like a chipmunk’s. Sugar-glaze clings to the corners of her mouth. I struggle to speak; my throat is tight and my face stiff. While Nairu chews the churro into a manageable bolus, she arches an eyebrow at my stunned expression.

“You look like a fish,” she says through the mush. “Were you swimming in your head?”

Jacqueline’s fingers trace the contour of my cheek, bringing a warmth that seeps beneath my skin.

“Leire, what’s the matter?”

Her motherly tone calms the pounding in my chest, but I avoid facing her concern. As I blink away the glare of sunlight, behind the row of carnival games, the rattling rollercoaster crests a ridge. During its zooming descent, the children shriek with joy, some passengers’ hair streams in the wind. If I were to look into Jacqueline’s cobalt-blues, I may confess that the universe and the human race are fucked unless I locate a reality-collapsing machine and tear it out by the roots.

“Ah, you know,” I utter in a strained voice, “just an intrusive daydream regarding one of my many traumas.”

“Ma pauvre chérie…”

I shake my head.

“No, no pity today. We have the right to enjoy a carnival of treats on a sunny November morning without the looming threat of an apocalypse.”

“Right you are. Our girl has expressed an interest in the tower, so how about we check out the most enchanting view of Donostia?”

I follow her pointing finger. Perched atop Mount Igueldo against an expanse of azure, the tower stretches upward, its sand-colored stones and arched windows washed in the sunlight, its crowning battlements and crenellations speaking of the days of yore.

Author’s note: today’s songs are “Sycamore” by Bill Callahan, and “Nantes” by Beirut.

I keep a playlist with all the songs I’ve mentioned throughout the novel. A total of a hundred and ninety-three songs so far. Check them out.

How about you listen to this chapter instead of reading it? Check out the audiochapter.

I went out of my way to write an essay regarding Leire’s trip to the past. Read it, will you?

You must be logged in to post a comment.