At the end of César Figuerido Street, we turned right and ascended a stretch of pavement winding along a towering wall of trees and wild undergrowth. Ferns draped their fronds over moss-covered gutters. Elena trailed close behind, gripping her backpack’s strap as she shifted the load. Her nostrils flared, her lips tightened, and sweat glimmered at her hairline. Her pale blues were fixed ahead with the determination of someone resigned to enduring torture with dignity.

“You doing alright, Elena?”

“Mm-hmm.”

“The path will level out soon.”

We crossed the road to the side closest to civilization. A middle-aged couple, the man sporting a yellow-and-white knitted earflap beanie, talked loudly in a Slavic language as they exited a parking lot and strode past us. A distant whistle blew, accompanied by a burst of cheering. Between the trunks of the trees, I glimpsed a deep-green field of artificial turf marked for football and flanked by two silvery lightning towers. Color-coded middle-schoolers pursued a ball, intending to kick it toward the opposite goal, while their relatives watched from concrete stands.

The hill flattened. Across a roundabout, dozens of headstones topped by crosses jutted out over a three-meter-tall stone wall.

“Oh, is that the cemetery?” Elena asked, her voice strained.

“It better be.”

“Are you taking me there?”

I shook my head.

“You sure? I could lie down on a slab of marble and catch my breath.”

“You’ll recover soon enough.”

“Or we could find a nice grave for you to bury me in. Save you the trouble of digging a pit in the forest. You could toss some dirt in my face and then just pretend that you never met me.”

“I’m not letting you die yet. We have a lot to talk about.”

“I guess we could bring up some topics.”

“Should I have taken you to another coffee shop instead?”

“No, I’m glad you’re showing me around. It’s a good kind of pain. I’d rather suffer than feel nothing. Besides, I think my heart rate’s approaching normal human levels. Tell me, Jon. Are any of your relatives buried there?”

“Yeah, my grandparents. Never bothered to locate their graves, though. They’re a bunch of bones now.”

We followed the path as it veered left, away from the cemetery. To our right, beyond a fenced garden, the landscape unfurled: Mount San Marcial, carpeted in rolling waves of pine and rising to a pitiful 220 meters. A titanic cloudbank, billowing over the mountain’s crest, eclipsed the chapel at its peak, that struggled to emerge from the treeline. The bluish-gray core of the cloudbank promised rain.

“The mountain looks different from here,” Elena said. “More alive.”

“We’re drawn to higher ground, where the world appears richer in meaning, where we feel safer. From a defensive standpoint, at least.”

“Is that so? Must be the Basque genes. But I get it. I wouldn’t want to be caught at the bottom of a valley when the floods come.”

Further along the sidewalk stood a three-story rectangular building composed of pale-cream bricks, its windows shuttered. Mortar lines across the facade formed a tight grid. Toki-Alai School. Rust had ravaged its fence; you could snag your clothes or scrape off your skin on the jagged edge of a post.

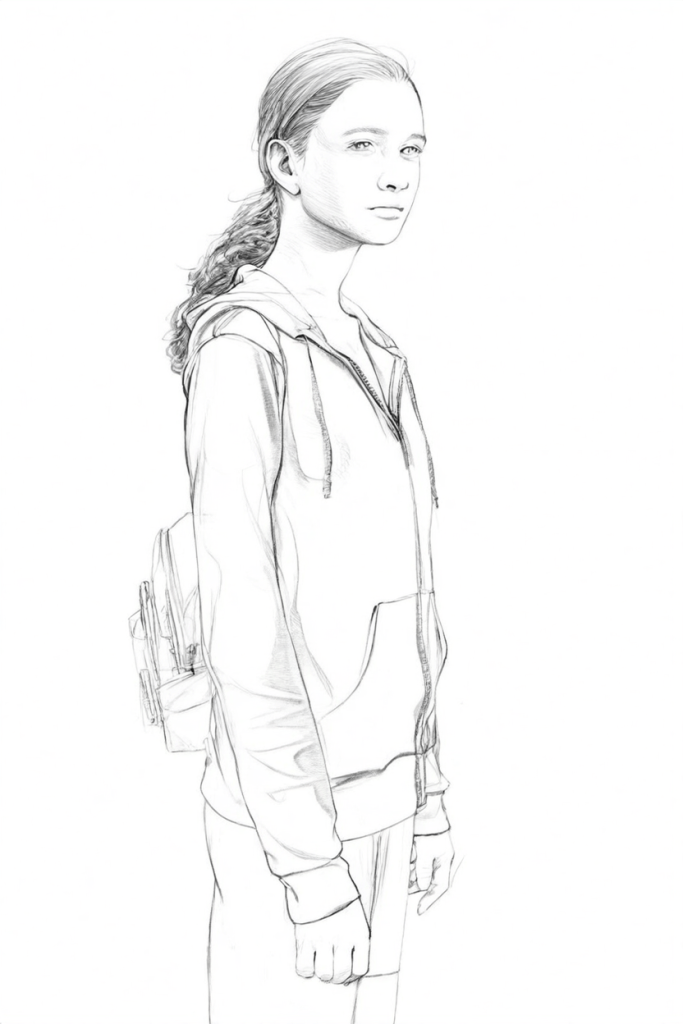

I looked back for Elena. She had crossed the road and stepped onto a grassy patch overgrown with weeds and tiny blossoms of yellow. Crisp white stripes ran down the side of her black joggers. Her pale neck curved elegantly, her almond-blonde ponytail dangling from the back of her head. Elena’s gaze had caught on the panorama: a sprawling array of trucks, some bright blue or red, lined in rows at a transportation yard as large as a stadium, in a stark contrast to the undulating green hills beyond.

When I approached Elena, I wished I had brought a camera, or could stop time. Sunlight cascaded down her face, sculpting her forehead, the bridge of her nose, her high cheekbones, her slightly-parted lips. From beneath the skin of her eyelids, those glacial blues glowed with an ethereal intensity. She evoked a wanderer from some bygone epic, standing before a war-torn vista. She could have been a bardic song, a lament, an ode to a fallen kingdom.

“I guess it isn’t a complete hellscape,” Elena murmured. “I have no idea where I am. This place, the fact that you exist and also have a weird mind… The more I interact with reality, the less familiar it becomes.”

A cool breeze wafted the scent of hillside grass and earth and pine, mingling with the tang of truck exhaust.

“In the spirit of sharing awkward stuff,” I said, “I regret that I will never drive a truck for a living.”

Elena whipped her head toward me, a mischievous smile tugging at the corners of her mouth, drawing dimples on her cheeks.

“What? Why?”

“Well, think of the solitude. All those hours to yourself on the open road, discovering new sights. They say the brain mainly reacts to novelty, so it can fend off predators. If you head away from home regularly, you’ll always feel alive. And imagine the conversations you could have with yourself in the driver’s seat. You could write, too, between naps, in motels or rest areas.”

“That’s a romantic and likely inaccurate portrayal of a trucker’s life. You’d have to deal with the hassle of loading and unloading cargo, navigating roundabouts in a hulk, driving at night. I picture them snagging their trailers on posts, falling asleep behind the wheel, slamming into cars, flattening old people. You’d have to sleep in rest areas, where any shithead could try to break into your cab.”

“You’d also command a multi-ton killing machine that can obliterate anything in its path, up to and including the laws of physics.”

Elena chuckled.

“Figures. You’re aching for some truckmageddon. Maybe with a side of strangling prostitutes.”

“Only a small percentage of truckers are serial killers, you know.”

“Oh, but I see it now: a trucker poet, crushed in the cab of his rig, his unpublished masterpiece scattered across the highway, pages soaked in blood. A crow would land on the rim of the shattered windshield and peck out his eyes.”

“Damn it, woman. Let’s just get to our destination.”

Past the school, a lawn caught the sunlight, forming a shimmering carpet of green. Across, set against the blue sky, loomed a pockmarked ruin, its rugged stones darkened by centuries of moss and grime. Small plants burst like wild hair from fractures and shadowed crevices.

“The hell’s this?” Elena asked. “A ruin out of nowhere?”

“Gazteluzar. Built in the sixteenth century, I believe.”

“So it was here. Gazteluzar, meaning ‘old castle.’ Quite the hyperbolic name, don’t you think? Barely qualified as a fortress.”

We crossed the lawn, our shoes treading over soft grass, and slipped under a rough archway into a courtyard. The sunlit walls rose in a jumble of irregular stones and smaller filler pieces, as if built hurriedly from nearby rocks. Bushes hugged the crumbling corners. I guided Elena toward a circular clearing enclosed by low, lichen-encrusted walls hinting at the foundations of a turret. At the circle’s center, decades of foot traffic had stripped away the grass, exposing bare stone.

Standing against a curved section of wall, a folding lawn chair faced us, its seat and backrest composed of red and navy interwoven strips of plastic webbing. In this dilapidated fortress, the chair looked like it had materialized from another dimension.

“You’ve brought a lawn chair up here?” Elena asked, amusement creeping into her voice. “Just for me to rest? What a gentleman.”

“I’ll gladly take the credit for the work of some anonymous benefactor.”

“It doesn’t even smell of stale beer or piss. The kind of neighborhood where nobody steals an abandoned chair, huh? I better take advantage of it before the owner comes along and shoos me away.”

Elena unslung her backpack and dropped it onto the ground. With a groan of relief, she sank into the creaking chair, its plastic strips sagging under her weight. Reclining with her eyes closed, she draped her arms over the armrests and stretched out her legs. After a couple of deep breaths, she turned her head and threw me a languid, heavy-lidded glance.

“You took one hell of a gamble, Johnny boy.”

“How so?”

“Bringing a woman you barely know to a secluded ruin. Most would think, ‘Does this big, bearded fellow believe I aspire to become an archaeologist?’ Nevermind that reaching this place requires an Olympic fitness level.”

“No gamble at all. You’re not most women. I brought you here because this is what you’re like.”

Elena lifted her head from the backrest. Her ivory skin accentuated those pale blues as they locked with my eyes, granting me passage through the darkness of her pupils into her abyssal void, a space preceding language, filled with black stars and white blood. Her lips curved faintly into a placid smile.

“You do understand me, don’t you? Better than anyone ever has. I should run away while I can.” She sighed, then lifted her backpack onto her lap. “But I’m fairly easy. I appreciate most places as long as they aren’t packed with people. Better than staying at home with my parents and their endless disappointment.”

Elena unzipped her backpack. Amid a crinkling of plastic, she pulled out the carton of Don Simón orange juice, unscrewed the cap, tilted her head back, and chugged. She then rested the carton on the ground between her canvas shoes. As she licked her lips, she reached into her backpack again and brought out her blue folder. She opened it and retrieved a stapled stack of papers.

“You may enjoy this one. Also takes place in a secluded clearing.”

Author’s note: today’s song is “Dear Sons and Daughters of Hungry Ghosts” by Wolf Parade.

Pingback: The Scrap Colossus, Pt. 16 (Fiction) – The Domains of the Emperor Owl

Pingback: The Scrap Colossus, Pt. 18 (Fiction) – The Domains of the Emperor Owl