After scaling the steep street, I paused to absorb the vista. Between the Spanish bank of the Bidasoa River and the reedy island dividing it from Hendaye, the broad, greenish-brown body of water flowed languidly, laden with sediment. A lone kayaker sliced through the calm surface, leaving a smooth wake that rippled like silk. Each end of the kayaker’s paddle dipped and ascended like a mechanical arm. As sunlight poured in the stream, its surface sparkled with a myriad little splinters of white.

Beside me, Elena’s nostrils flared as exhaled sharply through her mouth, fatigue etched across her features. She flung her head back. When she lowered it, soft locks of her ponytail caressed her neck. She fixed me with a look of concern.

“In moments like these, I’m forced to remember that I’m terrible at this activity.”

“Which one?”

“Walking. You don’t train your muscles by spending weeks at a time holed up in your bedroom.”

“Well, let’s replenish those lost calories with some snacks from the supermarket.”

The neighborhood BM’s automatic sliding doors opened for us, and we were welcomed by a tinny American song from the eighties. It conjured images of cruising in a convertible at night, with haloed streetlights blurring past. We ventured deeper through a narrow aisle flanked by refrigerated shelves and rows of half-empty wooden crates piled with fresh fruit. Knives scraped against each other. At the rear, behind the butcher counter, two aproned women chatted about their weekend plans as one of them dismembered a plucked chicken’s waxen carcass. Elena stared transfixed as a wing came off, then she followed me down the aisle.

“Did that bother you?” I asked.

“Bother me? No. I find butcher shops honest. No pretense. Just blood and bone and the admission that something had to die for us to keep going.”

Elena picked up a carton of Don Simón orange juice and a pack of Príncipe chocolate cookies, while I grabbed a bag of salted peanuts. When we exited the supermarket, she carried a plastic bag that dangled from her hand like a jellyfish. I asked her to turn around, then unzipped her backpack and tucked the snacks between the blue folder of excerpts and the backpack’s inner lining.

Past the outdoor tables of a bar, where retirees sprawled like bleached elephant seals, I unveiled the next leg of the hike: a steep, rugged concrete staircase bordered on one side by a grassy slope. Elena’s eyes widened at the towering steps, and she let her shoulders sag.

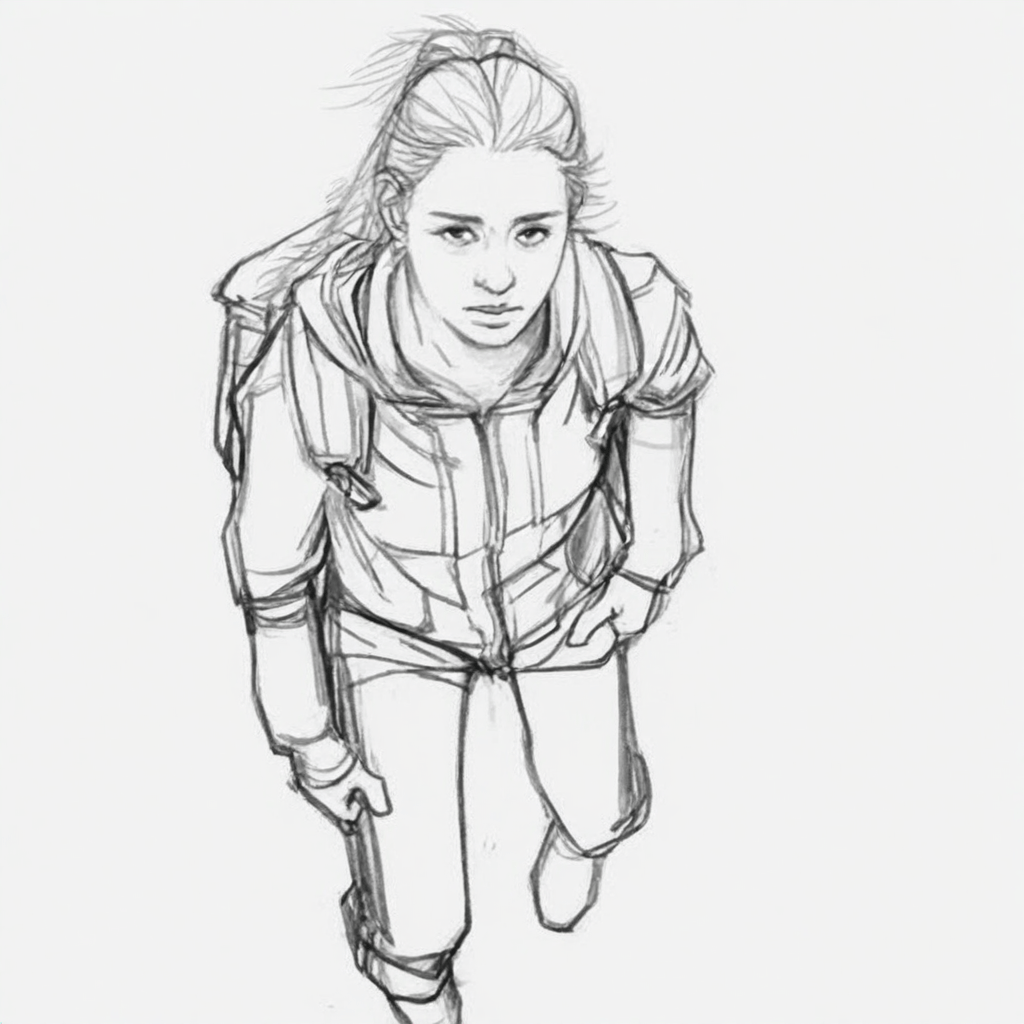

Midway up the staircase, I stopped to ensure that Elena hadn’t collapsed. Panting, she squinted up at me half pleading and half accusing. The top of her zip-up hoodie hung loosely, offering an unimpeded view of her jutting collarbones—a pair of fossilized wings—above a shadowed swell. Her joggers hugged her lithe thighs, tightening over their contours, while her untied shoelaces flopped around with each lift of her right Converse.

“Climbing out of the depths of urban despair,” Elena said, her voice coming in breathy spurts. “You’re not planning to sacrifice me at some altar up there, are you? Because right now it feels preferable to this sadistic cardio program you’ve got me on. My legs already hate me, let alone tomorrow.”

Once she reached the summit, she slid the backpack off her shoulder, dropped it, and crouched to tie her shoe. She then leaned back against the concrete post-and-rail fence, her chest heaving.

Across the one-lane road stood a once-white three-story house whose paint, battered by decades of rain, had peeled and flaked away in dozens of patches, exposing the gray core underneath. That house begged for a repaint or a renovation or a thorough bulldozing. It evoked the image of a self-loathing teen relentlessly picking at scabs.

We ambled along the sidewalk, attuned to the whispering breeze and the distant rumble of traffic, that arrived like the herald of a perpetually approaching storm. We stood at eye level with the third stories of a row of weathered apartment blocks nestled at the base of a grassy slope, their rear walls lined with deserted balconies. This neglected fringe of the city had been abandoned back in the seventies, left to decay, a derelict cemetery of brick and plaster and concrete.

Elena pointed out a cat. Across the street, atop a roadside embankment covered in leafy shrubs that edged a pasture with leaning fence posts, a mottled feline lay chicken-like, forelimbs folded and face buried in the grass.

“It isn’t dead, right?” she asked.

I crossed the road and approached the cat carefully. Its back rose and fell in the cadence of sleep.

Further along the sidewalk, beyond the post-and-rail fence, dome-shaped hydrangea clusters crowned its scrawny stems. The flower heads had shriveled into papery, brown husks. Elena asked to stop, then leaned back against the fence and stared at the bordering wall of foliage: a thick mass of shrubs, brambles and ferns beneath a canopy ranging from lime in the sun to shadowy emerald. A forest edge, untamed and untrodden. If you ventured in, you’d never again meet civilization.

Elena fidgeted with one of the drawstrings of her hoodie, twisting it tight between her slender digits. I was about to ask her if she was okay, but her lips parted.

“I’ve never been up here before. It’s weird, isn’t it? Places you can walk to but you’ve never visited. So close to where you live, yet foreign. Makes you wonder what else you’ve been missing. Also makes you feel like a stranger in your own life somehow. Was this where you wanted to take me?”

“No, it’s a bit further.”

The shadows under her brows deepened and her eyes glazed over, as if fixating on a film flickering across the screen of her mind.

“I’m standing on the threshold between two worlds, neither of which I belong to. Our ancestors built this one not only for themselves but for their descendants, most of whom they’d never meet. Yet along the way, something broke. I regret not having been born a thousand years ago, or not being able to visit another planet. Absurd, right?”

She tucked her hands into the kangaroo pocket of her hoodie, her fingers fumbling within as if searching for something. Her shoulders tensed, and a sudden shudder rippled through her.

“Listen, Jon. When I was a kid, I took a school trip to some town I haven’t visited since and whose name I forgot. As I followed the group along an esplanade, I noticed a hitching post. I still see it vividly. I think they used it to tether cattle during local celebrations. One of the teachers mentioned that a few years earlier, a girl on another school trip had gotten kicked in the head by a hitched horse and died instantly. The teacher dropped that information like she was telling us about the weather. Imagine those parents getting the call. ‘Sorry, your daughter’s dead because she approached a horse from the wrong angle.’ And the teachers on that trip, they had to carry the trauma of her death for the rest of their lives. How do you even process it? One minute everything’s normal, the next minute a little girl lies dead with her skull smashed in. And why? Because nobody taught that child to approach a horse from the front so that it can see her? Perhaps she had never been near a horse before, and wasn’t aware of how dangerous they can be. I can see her grinning as she scampered over to pet it. Should her parents have also taught her to steer clear of boars or bulls? Not to reach her hand out to pet a snake?” Elena glanced away, then spoke in a low, hoarse voice, as if she dragged the words out from the depths of her throat. “What an absolute fucking waste.”

“Were you waiting to bring that up, or did it just pop into your head?”

Elena rubbed the outer corner of one eyelid.

“The second one. My brain decided to sour the moment by digging up an old memory that should have stayed buried. I was thinking about how our ancestors built a world for us, and my mind went, ‘Cool, but what about that one girl who had her brains bashed in after a fucking horse kicked her in the face?’ That kind of thing happens too often to me. This time maybe because I’m teetering on an edge, with civilization behind me and nature ahead. My brain’s way of reminding me how fragile life is. One wrong move and it’s over. That’s all it takes, right? A teacher looking away for one moment, a little girl who didn’t know better, a fucking horse doing its horsely things. Life’s just… waiting for the kick to the head that ends it all. And I’m not convinced that what lets us function, as a species, is a defense mechanism. I think it’s more like a collective delusion. We pretend we’re safe so that we bags of flesh and nerves can get out of bed every morning and put on our clothes and go on about our lives without losing our shit. But the truth is always there, lurking behind every corner. That’s part of why I can’t connect with most people: they’re so committed to the lie that they get angry when someone refuses to play along. They call it pessimism. I call it paying attention.”

Author’s note: today’s song is “Caribou” by Pixies.

Pingback: The Scrap Colossus, Pt. 17 (Fiction) – The Domains of the Emperor Owl