A group of six twenty-somethings swept in through the gate of Bar Palace’s fenced patio. At the forefront of that posse, two young men sported fitted T-shirts and jeans, while the leading lady wore a cream blouse layered under a fuzzy, warm-toned coat paired with ankle boots. The group sauntered between the tables and the low stone borders enclosing boxwoods and sago palms. Each face bore a pristine smile as if etched permanently. Had Elena continued talking, their booming voices would have swamped hers, and judging by their tone, she should have thanked them. They headed towards the back of the patio, where an open-sided marquee shaded a dozen tables.

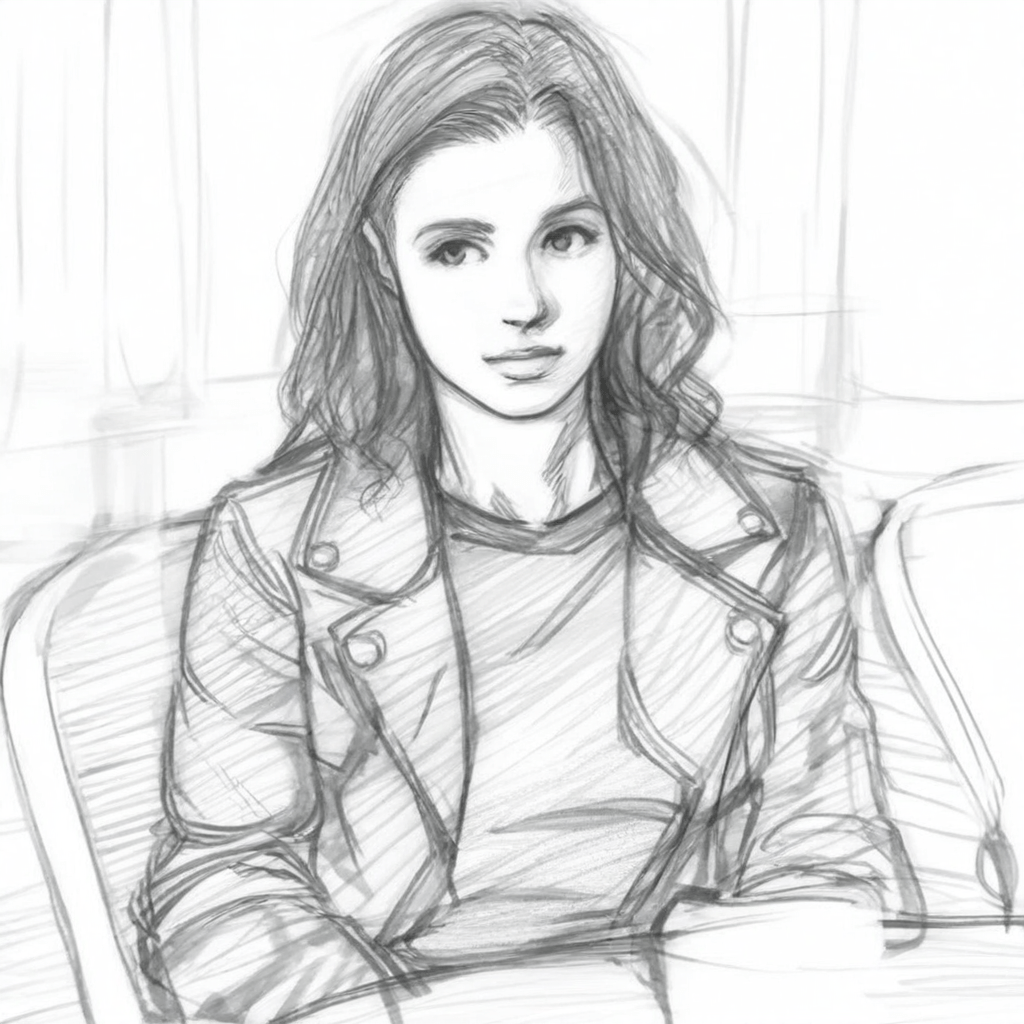

Elena crossed her arms. She turned one ear toward the intruders’ youthful cackling, which caused curved locks of almond-blonde hair to slide from the collar of her jacket. Along with her wary gaze, she evoked a stray cat that had come across a human while prowling the streets at night.

She had been speaking so earnestly, but now she risked clamming up. I should hurry to cocoon her within a web of words.

“Are these novellas finished?”

Elena uncrossed her arms and let out a weary sigh.

“I wrote six stories back-to-back. Didn’t I tell you?”

“Damn. Have you sent them somewhere?”

Her pale blues softened with regret, eyebrows furrowed. She drew her shoulders in and lifted her slender index finger to her mouth. Her lips pursed around its tip, then the muscles at the corners of her mouth contorted as she nibbled on the nail. Her gaze drifted down. When she pulled her finger, its tip glistened with saliva.

“I wish I hadn’t. It would have been better to retain in the back of my mind the delusion that once I sent the manuscripts, these stories I worked so hard on, that meant so much to me, that I bled for, I’d get the call, some editor at a big house saying: ‘Oh, what a gem this is! Here’s your prize, your publishing deal, and your movie adaptation!’ If my stories were truly great, surely the world would notice them no matter what, right? Someone would care. So I divided the novellas into two collections, then went through the mind-numbing process of figuring out to what contests I could send them. Do you know that the terms and conditions of some contests specify that they’ll reject any submission that features profanity or violence? I mean, are you fucking kidding me? What world do they live in? Anyway, I sent my collections to a couple of the less stupid contests. They didn’t even reach the elimination rounds. What a bummer, huh? Afterwards I figured, well, I’ll send them directly to the publishers, those that accepted unsolicited submissions. Only a couple bothered to respond, a few months later. ‘We regret to inform you that your book does not meet our current needs.’ You know, much worse writers than me are getting published, so I had figured I could squeeze in. Fucking moron. I got my hopes up for nothing.” She tilted her head and stared at the leaden sky. “And I did it for money. I was trying to figure out how to make a living doing something that didn’t make me want to strangle myself with an extension cord. But realistically, if a professional of the industry recognized my work, I’d have to deal with editors, publishers, and other strangers. They’d try to fix in my stories whatever offended their sensibilities. And I’d have to care about marketing. How would you sell these stories, which are symptoms of the radioactive darkness that’s been growing in me since before I took my first breath? I would have to go on book tours, and attend conventions. I’d be expected to sit in front of a room full of people staring at me as if I were a human being instead of a monster afraid of the light.” Elena’s shoulders heaved. She shivered like shaking off a gruesome vision. “But I don’t have to worry about those horrors ever becoming reality, do I? My work has no professional future. The gatekeepers would react to my stories the same way Isabel did. Lacks empathy, they’d say. Too dark, cynical, depraved. And I don’t write about the Civil War, which vastly reduces your chances of being published around these parts. Besides, do I really want to give my stories to the world? I just need to get the words out, to stop them from eating me alive. It’s like vomiting. You don’t serve it on a plate and invite everyone over for dinner, do you?”

“I find your puke delicious.”

“Well, you’re a weirdo. Which I like. But they’ll just see it as another mess to clean up.”

Two women in their thirties, a blonde and a brunette, seized the vacant table at our left as they bantered in a torrent of Basque. The blonde’s laughter erupted, her jaw gaping like a shark snapping at prey. Even after they sat, she flailed her arm, clutching a smoldering cigarette that set curls of smoke pirouetting. Their voices carried the confidence of those who knew their place in the world and were making the most of it. As a waiter in a stark black uniform swept over to take their orders, Elena glanced sideways at the pair like they were aliens.

“Anyway, Elena, I’d love to read the full novellas.”

Her lips twitched. She tensed her shoulders and held her hands on her lap as if steeling herself. Then she lowered her head, brows knit.

“Not yet. These are… appetizers.”

“For what main dish?”

Elena bit her lower lip and shot me a hesitant look.

“Something I’ve never shown to anybody.”

Was she trying to prove whether I was worthy of reading her secret work? On her lap, the fingers of her left hand had retracted and curled into a claw, metacarpals jutting from her pale skin. That hand trembled. I lifted my gaze to her eyes, but her fallen lashes obscured the irises.

“I’m not used to being seen,” Elena said in a voice like a rusty gate opening. “It’s a lot to deal with.”

“Hey, whatever your secret story is, I’ll devour it. Can I ask for some details?”

“I don’t know if I’m still working on it, to be honest. It’s sort of… frozen. I just need to keep moving. Keep my mind from sinking back to where it left me.”

“Where was that?”

“Somewhere dark and cold and very far from here.”

Those pale blues, that seemed to have seen it all and wanted to see no more, teetered on the verge of thinning out and revealing some hidden passage. As if catching herself, Elena raised her palms to rub her face. A thick lock of shimmering almond-blonde hair tumbled from her ear and swayed. When she tilted her head back to rearrange her cascading hair, the overcast light of late afternoon sculpted her jawline, highlighted her cheekbones, and caressed the dusty-rose curve of her lower lip. In the span of her neck, the twin cords of her sternocleidomastoids, running down diagonally to her collarbones, flexed like silk ropes beneath her skin.

“Whenever you feel ready, Elena, I’ll be waiting. I’m not going anywhere.”

“Yeah. A week ago I was sure I’d never show that story to anybody. But now, I don’t know. Maybe you could handle it. What were we on about? Ah, right.” She massaged her temple with her index and middle fingers. “I had been trying to find a way to make money that wouldn’t force me to interact daily with human beings. Otherwise I’m doomed to live at my parents’ until they kick the bucket. I could sell my body, I guess.”

“If you monetized it well, you’d make a killing.”

“And lose a part of myself with every transaction. So, Jon. Do you have a job, or do you live on an inheritance? Or in a cardboard box under a bridge?”

“Is this the part where you determine my value to see if you should stick around?”

“You’re the only person in the world who’s willing to listen to me babble. And you even wait patiently at the end of a sentence to see if I’m done talking. But if you turned out to be a murderer, then I’d have to weigh the pros and cons, the enjoyment of our conversations versus the risk of ending up as a severed head in your freezer. Does that defensiveness mean you’re also a failure?”

“I’m an IT technician at Donostia’s main hospital, fixing network issues, granting users access, etcetera.”

“Sounds like a nightmare.”

“It’s a shit job, but it keeps me afloat. And as you suspected, I’m indeed a failure. I never dreamed of ending up tied to such a job.”

“At least you have access to the medical records of most people in the province. That should give you an advantage over the common murderer, and it might be fun to look up people from the past and see if they’re now riddled with STDs.”

“If you pry into someone else’s medical record when not authorized to do so, you’ll receive a call from HQ, and if you can’t justify yourself, you may end up in jail.”

“They take the fun out of everything, huh?”

“What about you? Want to share your work history?”

Her head dipped in a timid bow, brow creased. Her pale blues tried to hold my gaze, but her lids flickered, then her eyes darted down. A slight grimace pulled at her lips as she clutched the moth pendant.

“I’m not proud of my job experience, Jon.”

“I hadn’t assumed otherwise.”

“Well, as I’ve established, I’m a leech that lives off her parents. They aren’t pleased with the situation, so they’ve pushed me to find work, even part-time. The issue is, when you’re born with radiation for blood and chaos for bones, you’re not exactly employable. After high school, I didn’t continue my studies, not even a vocational program. I couldn’t bear the thought of wasting more time in a classroom, pretending to be interested in whatever the teachers had to say, surrounded by people I had nothing in common with. For the next couple of years, I did little more than lie in bed and masturbate. I had my first taste of employment during my twentieth summer, as a waitress. Can you imagine? I don’t know how I lasted more than a day. The goons I had to consider my coworkers were a bunch of loud, obnoxious idiots who kept inviting me to hang out after work. Soon enough they started calling me a bitch behind my back. I also had no clue how to talk to customers, and of course I didn’t want to. I discovered that my troubles with basic math may indicate a mental retardation. Anyway, the manager fired me before I could quit. He said he couldn’t understand how someone could be so incompetent at serving drinks. He also called me a bitch, but to my face. Then, I worked at a bookstore. Seemed like a fitting job for an aspiring writer. Back then I still believed I could fake being human enough to fool everyone. I watched and mimicked until I mastered certain norms, although it exhausted me and made me hate people even more. I lasted three months, my longest stint, before the fluorescent lights and the noise and the forced small talk drove me to have a nervous breakdown in the poetry section. My boss sent me home early, told me to take a couple of days. But I never went back. Finally, the call center gig. Apparently I thought torturing myself with constant human interaction was a penance I needed to endure. I should have swallowed a bottleful of bleach instead. That job ended with me telling a particularly nasty client exactly how many ways the human body can fail before death takes pity on you. So yeah, I’m unemployed. Have been for a while. And those humiliating examples of my failure as a member of the species were interspersed with periods in which I did little more than lie in bed and masturbate.”

“Living the dream. Too bad I couldn’t join in.”

She smiled with the vacant, distant stare of a prophetess gazing into the embers.

“Jon, how do you compete in a world where everybody is expected to be whole and perform their role perfectly? It’s like trying to participate in a sprint while missing a leg. Five days a week, if not more, waking up at seven and forcing yourself to head into a workplace where you’ll be surrounded by people and ordered to carry out tasks. The clock felt like a guillotine blade dropping again and again onto my neck, chopping off pieces of my life I would never get back. For a paycheck that wouldn’t even allow me to buy my own place unless I paired up with another wage slave. The thought of enduring it for decades filled me with absolute horror. I’d wake up in a panic, thinking, ‘It’s morning. I have to do it again.'” Elena shut her eyes, then took a deep breath. “I would expect the majority of the population to be unemployed, or else quit or be fired after a week. That they go about their business without breaking down or having to drown themselves in meds emphasizes that I don’t belong among them.”

“You’re too sensitive, Elena, but that’s alright. The problem is that society favors psychopaths.”

“My parents… they try to understand in their own way, even though they must be sick of supporting a grown-ass woman. They send me job listings like maybe this time it’ll work out, like maybe this time the monster inside won’t rear its horned head and destroy everything. But we know how the story ends, don’t we? I guess that’s how normies became the blueprint. They get pissed on over and over, but they think, ‘Well, next time it may be water.’ A lack of pattern recognition, don’t you think? But that allowed them to out-reproduce the competition, and that’s how you end up with fiat currency. Meanwhile, I have trouble buying a toothbrush.” Her voice had dwindled to a hoarse whisper, as if her throat were clenching her vocal cords. She hunched over, elbows on the table, and clutched at her head with trembling fingers, tousling her almond-blonde hair. “I can’t. I can’t go through that again. I can’t spend the rest of my days trapped in an office or store, or any place that requires me to interact constantly with the human race. I can’t do that to myself. I’ll end up hanging from a ceiling beam.”

“We’ll find a better solution for you.”

Elena jerked her eyes upwards, suddenly realizing she had a witness. Loose locks framed her parted lips, her crinkled brow, her helpless blues that cast an apologetic glance. Then she lowered her head, spread her elbows, and pressed her hands onto the table. The wrinkled sleeves of her jacket clung to her arms, slender as birch branches. Through the cascade of her almond-blonde hair, only the soft triangle of her nose emerged from her pale face.

I spoke calmly.

“Those whose brains urge them to create new things shouldn’t have to compete in a rat race. Imagine if Michelangelo Buonarroti had been forced to work at bank, or if Beethoven had worked as an accountant and could only compose in his free time. How much beauty has been lost to the world because creative minds had to spend their lives chasing money, or simply surviving?”

“I’m neither Michelangelo nor Beethoven,” she said to the table, her voice creaky. “There’s no demand for what I do. And who would foot the bill for me to indulge myself, huh? Just because I’m broken doesn’t mean I deserve handouts.” She straightened her spine, then combed her locks back while avoiding my eyes. “Writing full-time would mean staying holed up in the cave that is my room, coming out only to eat and drink and piss and shit and bathe, if I could be bothered to bathe, and then back into the cave. Nurturing this darkness until it consumed everything. Until there was no Elena left, just a monster that feeds on the world’s misery and shits out words that no one will read.”

“Haven’t you been doing that already?”

“I wrote the six novellas in a frenzy, under pressure. I produced them longhand in the study room at the library, because if I did it at home I’d be dreading the next knock at my door, then either my mother or father would enter with a fake smile, sit beside me, and bring up some fucking course or job offer, while pretending not to notice how I shrank further and further into myself. If I had the license to write full-time and nobody hounded me to become a functional member of society, that’d be a different matter.”

“Either you refuse to write, which would cause you to fall apart, or you submit and create your stories, feeding the monster.”

“Fucked either way, you mean? The monster demands its tribute, whether it’s in words or pieces of my sanity.”

“You’ve envisioned your end a myriad times. You’re responsible for most of those demises, through pills, blades, nooses, or leaps into the void. We’re doomed to exit this world in an undignified manner, so you may as well produce as much beauty as you can along the way.”

“A tragic artist painting with her own blood before the inevitable end, huh? Something terrifies me, Jon… What if this pain, this darkness I’ve been carrying around like a tumor since I was a kid… what if it could actually mean something? Help me create a work of art worth remembering? That’s almost worse than believing it’s all meaningless.”

“How come?”

“Then I’d have a responsibility, right? To what? To whom? To… well, the artists I look up to, who don’t even know I exist, although they make me feel less alone? To some hypothetical future reader who might find solace in knowing they’re not the only monster trying to pass as human? I’d feel obligated to carry that weight as it crushed me.”

“You have a responsibility to your own uniqueness. You’re the only person in the entire world who can write your stories. They might not save you, but they may help someone else. And you will have contributed something unique to the world, which is more than most can claim.”

Elena stared off into the distance, lips pressed together. Her right hand twitched. Then, after dipping her head, the fingers of that hand spasmed as if typing in fast motion. She stayed silent, so I spoke again.

“Haven’t you ever come across a song or story and thought, ‘Shit, if this artist hadn’t wasted half of their life drunk, or if they hadn’t overdosed at twenty-seven, think about the amount of amazing art we could’ve gotten.'”

“Well, I’m past twenty-seven, thankfully or not.”

“You have a gift, Elena, even if it’s also a curse. So you must do your very best with it.”

“Maybe I do. How many times have I listened to her music and wondered what other masterpieces she could have created if life hadn’t beaten her down so hard? And here I am, letting this darkness eat away at me day after day, telling myself it’s inevitable. No one else has quite my flavor of fucked up. But this hope you’re trying to inject into me… It’s dangerous when you’re made of radioactive waste. It may make you think you’re worth something. In the end, though, I know what I was born to do: carve the world a wound in my shape.”

Laughter erupted from the open-sided marquee at the rear of the patio, and youthful voices tangled in a frenzied medley as if competing to be heard the loudest. Elena flinched—her shoulders shot up and her jaw clenched. She glared warily over her shoulder like a soldier scouting for snipers. Then she dropped her gaze and sprang to her feet, pushing the rattan chair back. Her jacket fluttered and her moth-shaped pendant, suspended from its chain, glinted in the late-afternoon light and patted against her breasts as she collected the printouts and inserted them into her folder.

“Let’s go. I’m getting real antsy.”

Author’s note: today’s song is “In the End” by Linkin Park.

The Deep Dive pair had a lot of interesting things to say regarding this part.

Pingback: The Scrap Colossus, Pt. 12 (Fiction) – The Domains of the Emperor Owl

Pingback: The Scrap Colossus, Pt. 14 (Fiction) – The Domains of the Emperor Owl