I recommend you to check out the previous parts if you don’t know what this “neural narratives” thing is about. In short, I wrote in Python a system to have multi-character conversations with large language models (like Llama 3.1), in which the characters are isolated in terms of memories and bios, so no leakage to other participants. Here’s the GitHub repo, that now even features a proper readme.

Three or four days ago, the RunPod templates that render voices stopped working. At least one of them is operative again, so that’s great. In the meantime, it was off-putting enough for me to use the system with silent characters that I took advantage of the break to improve fundamental parts of the app. I’ve forgotten most of what I’ve worked on, but the point is that I’m back, so here’s more voiced narrative.

I implemented a Travel action that is only accessible when one moves from an area (such as a city) to another. The ongoing adventure in this eldritch setting had led us away from Providence toward some interdimensional rifts in the wilderness, to where a missing girl could have traveled or have been brought.

After rendering those voice lines, I realized that the travel audio should be produced in the player’s voice, not the narrator’s. Oops. Anyway, fixed for the next time.

Such long voice lines require about forty seconds in total to render. I thought that they were perfect candidates for parallelism, which Python isn’t particularly fond of, but after implementing it, turns out that the RunPod server that handles voice generation isn’t fond of multiprocessing either, so I had to revert all that programming.

My player character had some observations to make about his new surroundings.

The team gathers in the wilderness, an unusual setting for scholars and police detectives.

I usually discover new features to implement as I’m playing, whenever I realize I’d love for some functionality to be present. At times, as I was chatting, I wanted for the AI to give me a “push,” to move the narrative just a few sentences forward based on the ongoing dialogue and what it knows about the characters. So I implemented a button that injects a narrative beat. That part at 2:55 in the previous audio is an example of it.

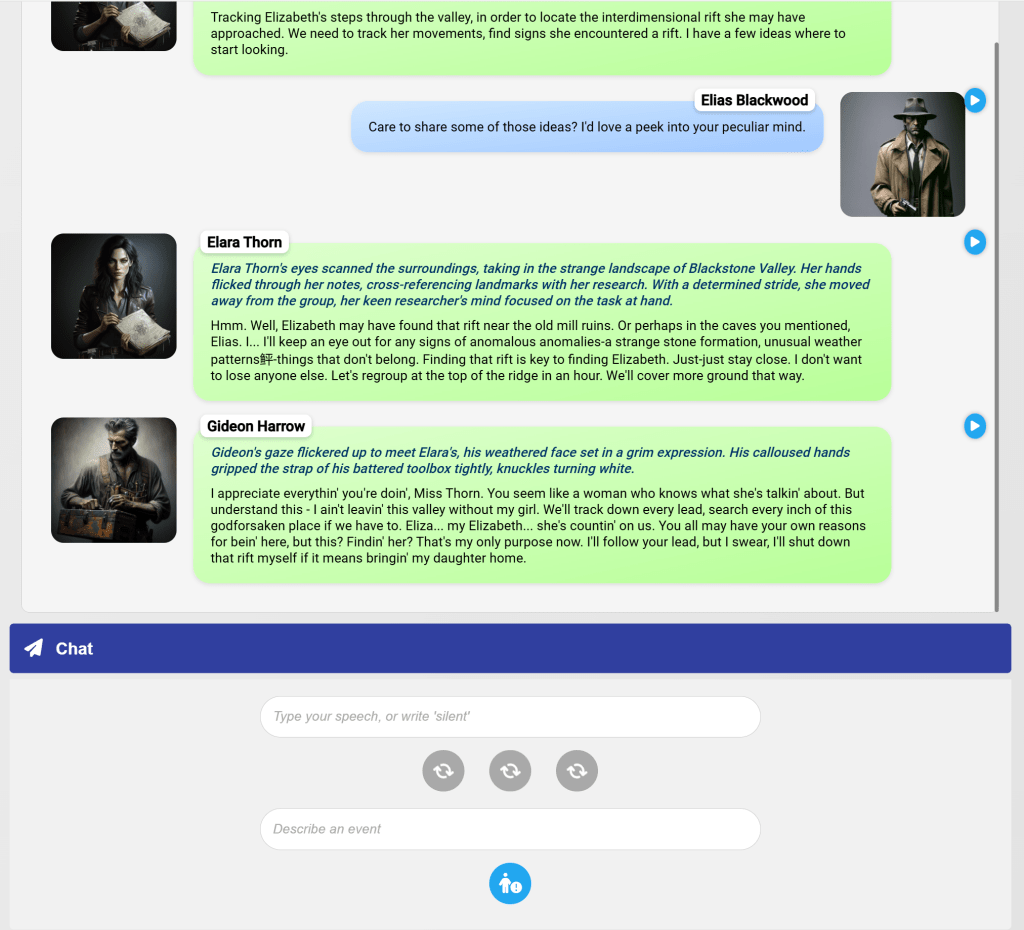

I also had to redesign the interface of the chat page. Those buttons are showing spinners because the server is processing a speech part for that form. The first button sends the speech written above. The second button produces ambient narration, and the third a narrative beat. The part below allows the user to introduce an event; sometimes I just want to state that the characters are doing something without having to trigger a dialogue response from other characters. The event gets voiced, and injected into the transcription so the rest of the characters can react to it.

Before we continue with the narrative, which will involve the results of an Investigate action, I wanted to showcase some character portraits that the app has generated these past few days for other test stories.

It’s so strange to have gotten used to this level of quality coming from artificial intelligence. My reaction to seeing those pictures generated for a newly created character was, “Oh, that looks good. Moving on.”

Anyway, here’s the result of the Investigate action:

I considered for a while if I should create a Track action, but that isn’t different enough from an investigation, as far as I’m concerned. One of the great things of this LLM-led system is that I had no idea what was going to happen, and now it’s “canon” that Elara Thorn has found a rift, and also discovered an artifact that could guide them to rifts on either side of them.

Forgive my player character for his inability to say “vicinity” correctly. He’s way over his head.

Pingback: Neural narratives in Python #16 – The Domains of the Emperor Owl

Pingback: Neural narratives in Python #18 – The Domains of the Emperor Owl