I’ve read through this series a third time since I reviewed it in this post. I’ve checked out most of Furuya’s stuff, such as Boku to Issho, Wanitokagegisu, Himizu, and Ciguatera, among which Ciguatera may be objectively his best, but Saltiness speaks to me to an extent that has made it my second favorite manga series after Asano’s Oyasumi Punpun.

Saltiness is the story of, for me, a clearly autistic dude who lives in one of those isolated Japanese towns with his younger sister, who is a teacher. We don’t know it yet, but they went through hell growing up: their mother abandoned them, and our generally deranged protagonist had to steal and loot in order to provide for his helpless little sister. As a result, even about twenty years later, he’s terrified of anything bad happening to her, and her happiness is his one goal in life, to the extent that once she manages to set up her life in a way that doesn’t require him anymore, he plans to arrange an accident in the woods to die and let her continue without needing to worry about him.

When the story starts, our oblivious protagonist is busy training to remain stoic in the face of all the outrageous nonsense in the universe. He pictures bizarre phantoms in his imagination, that pester him with philosophical questions and test his mental fortitude.

One of those days, his grandfather, the relative that took them in years ago, makes the protagonist aware of something horrible: as long as his little sister has to worry about his autistic ass, she won’t get married, won’t have a family of her own, and will end up miserable. Our protagonist understands that if he’s to achieve his goal of making his sister happy, he should become a financially independent adult. Thus, even though he doesn’t even know the name of his town, he hitch-hikes to Tokyo in order to achieve this goal.

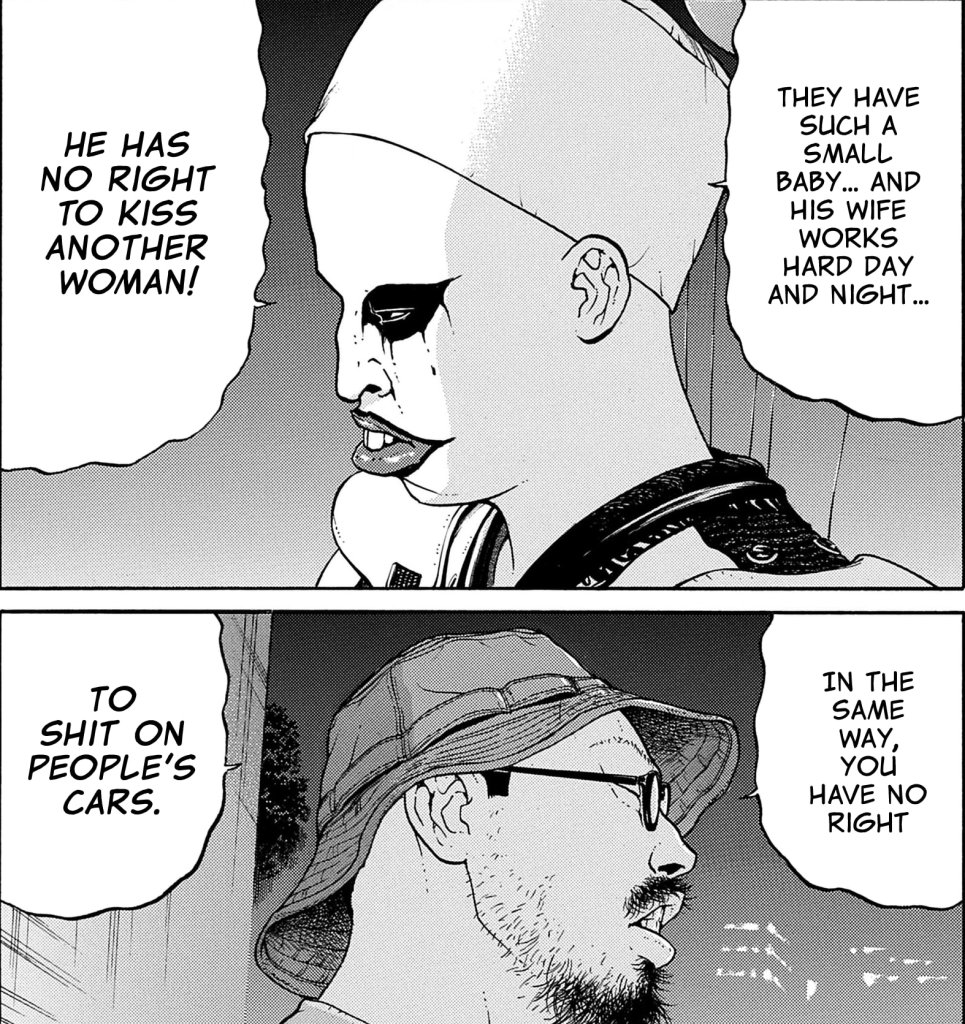

What follows is a deranged, outrageous tale filled with fascinating characters, most of whom exist in the fringes of society: a garrulous gambler with little self-control, a student who’s forced to steal panties to support his family back in the sticks, a senile old man that believes he alone knows the secret that will topple the US, a clown who punishes cheaters by shitting on their cars, a forty-year-old mentalist who lives with his mother and hasn’t talked to other humans since he was eighteen, an arrogant prick who will only speak nonsense to those he deems more intelligent than him, a successful but suicidal novelist on a spiral of declining mental health, etc.

Throughout this journey, the protagonist will shift his perspective on how to confront the mysterious monster called life, to figure out what, ultimately, constitutes happiness for him. I was very pleased with the ending.

Furuya’s works share the same elements: men on the fringes of society try to improve their lives despite having few resources, and facing somewhat episodic, at times horrifying stuff that they’ll nevertheless have to endure through. I’m talking about kidnappings, torture, and rape in the extremes, mingled with mundane stuff like trying to figure out if your family members will be out of the place when you bring your girlfriend over. Curiously, after some of the most outrageous, potentially life-derailing stuff, the characters involved keep going, having grown a little bit after the experience but otherwise unaffected.

All of his protagonists, if I remember correctly, deal with intrusive thoughts and bizarre daydreams. Along with the way his characters talk and his outside-the-box narrative choices, I’d say that Furuya’s brain must be quite similar to mine, which naturally ended up making him my favorite overall. I’m instinctively drawn towards writing similar stories.

I see myself rereading this series plenty of times throughout my life. I’m already rereading his Ciguatera, a fantastic work on its own right. It’s a shame that Minoru Furuya remains a stranger even for many seasoned manga readers.

Pingback: Minoru Furuya: my favorite manga author – The Domains of the Emperor Owl